The following is from a series of articles I wrote for Living Water, the choir I directed at Valley Church (Cupertino, CA) from 1987-2003, and at First Presbyterian Church (Mountain View, CA) from 2003-2011. While Living Water is no longer in action, the ideas I had the opportunity to present are just as valid now as then.

If you’re in any sort of normal choir, you have to practice! Here are my thoughts on what goes into rehearsal. All concepts here are time-tested, mostly because I had to learn many of them by trial and error on my own (but don’t we all…)!

Rehearsal is a tremendous part of every choir’s ministry. If you’re in any sort of a normal choir, you spend much more time practicing than you do performing. You spend most of your time together preparing rather than displaying the results of that preparation. Even if you go on tour and sing a set program in dozens of places, you’ll still spend nearly all of your time practicing.

Maybe you’re a singer who wonders why you have to spend so much time practicing when once through seems to be enough to do the job. Why does the director work on that particular anthem for so long for so many weeks in a row? Certainly, this can be frustrating sometimes, especially when the going is rough.

Maybe you’re one of those hundreds, possibly thousands, of volunteer directors who have arrived at your position by dint of someone saying, “(Insert your name) sang in a choir once, so we know who’s qualified to be our choir director!” And you think, “Yeah, right” but you accept the position (after all, no one else is volunteering…) and hope you can remember exactly what it was that Mr. Jones did at your junior high school – and then tough it out from there.

Or maybe you’re one of those “congregational members at large” who wonders about why the choir sings for three minutes on Sunday morning after practicing for an hour or more on Thursday night (why do they need all that time, anyway?).

Let me start (well, really start) by saying that I’m one of those directors who was thrust into the position by someone else’s decision. I must admit that I wasn’t all that sure of my being a good choice for the job, and there certainly was a good amount trepidation over learning so much “cold turkey.”

My educational background included a double major in math and chemistry which definitely was oh-so-musical, my work experience at the time included college jobs and a couple of years in computer stuff. Yes, I had about fifteen years of piano and clarinet, plus other musical (mis?)adventures, but the only conducting I’d ever done had happened at Montera Junior High on that day Mr. Yob put me on his podium for a couple of minutes.

And so I enrolled in the School of Hard Knocks (in which I still am a full time student), and started to learn the ministry of being a choir director. More than fifteen years later, I’m much more comfortable with leading a choir, and I’m enjoying myself tremendously. But I can’t fairly tell you that without letting you know that I went through a lot of mental anguish on the way because of what I needed to learn.

So this dissertation is here to give you ideas. It’s here to amplify your current knowledge. It’s for Daryl, who wrote from Singapore to ask about what might work for him as a student director in his college choir. It’s for Wanda in the Midwest who had a little difference of opinion with a couple of her choir members about how to pronounce “remember.” And it’s for you, especially if you’re one of those dear friends who labors onward, hoping to lead your choir to add some gold, silver, and precious stones to the glorious Church which those saved by faith in Jesus Christ comprise.

I was astonished at how voluminous my initial outline was when I started planning this exposition. There were over forty index cards of topics, and I knew I had to order them in a more coherent form if I was going to survive the writing. As I stared at what I had, the idea of “guiding principles” emerged:

- Guiding Principle I: Work in manageable chunks.

- Guiding Principle II: Isolate technical aspects as required.

- Guiding Principle III: Integrate the technical aspects.

- Guiding Principle IV: Allow enough time.

- Guiding Principle V: Infuse an understanding of “message”.

- Guiding Principle VI: Plan your rehearsals.

- Guiding Principle VII Use nonverbal communication.

- Guiding Principle VIII: Have a sense of humor.

We’ll look at these principles one at a time (now that’s a stupid thing to say – there’s no way to approach them except one at a time…) starting with the first one (well, duh!):

Guiding Principle I: Work in manageable chunks.

The essence of doing any job effectively is to break into pieces which each are small enough to tackle singly. Then you solve each of the pieces and put the answers together. Eventually you get to a point where all the pieces have been put together into an integrated whole, and voila’, the job’s all done!

It occurs to me that one of the relatively intractable parts of choral singing is that every technical aspect is tied in some way to every other technical aspect. For instance, playing with diction can affect intonation, and tweaking intonation can affect tone. This means that even in the simplest of passages you have a lot of things to bring under control, and that you must also bring them under control simultaneously. So this brings us to the first key idea within our first principle:

Repetitions are essential.

The reason repetition is essential is that the human mind is best fitted to learning incrementally. For instance, most of us don’t learn algebra by taking the book home and learning it in one night. Rather, we take quite a few months learning lesson after lesson, adding new ideas to our mental toolbox one at a time. As we became better-versed in the subject, our facility with the theories and formulae was increased by doing homework – repetitive exercises – so that we could learn to think in the proper way.

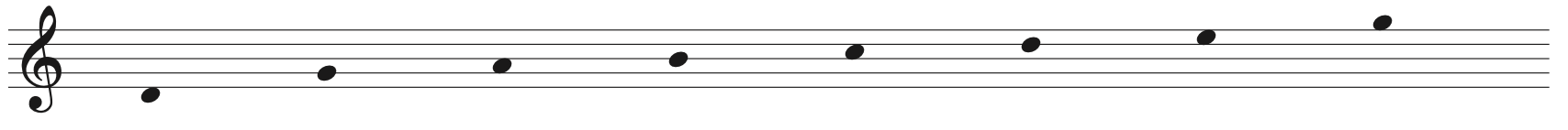

In the same way, it’s essential to sing passages of music over and over in order to master them. It also means that with each successful repetition you, the director, can add a new concept to the accumulation of concepts which your choir is demonstrating. The general idea is to start wherever you are and to bring the music to where you want it to be one step at a time.

An aside: Repetition is also good for you, the director. It’s a way to attain a better feel for how each voice sounds. It also gives you an opportunity to develop your interpretation of the music. Repetition creates an atmosphere where musical growth is tangible – you can come away from the rehearsal positively knowing that you’ve made progress. It also provides a natural framework for innovation: you can try new ideas out and keep them if they work, or toss them if they don’t – and you can do so at minimal cost, because there’s always the next repetition to try for new success.

However, pure repetition isn’t enough. You must also heed the second idea:

Work on small sections.

It’s just not possible for the average choir member to work meaningfully on an anthem by singing it all the way through time after time. Here are some reasons why:

The three-minute length of an average anthem is too great for attaining a meaningful appreciation of technical concepts which occur with a time granularity of measures or fractions of measures: Diction, intonation, etc.

Such long-length repetition practically guarantees that trouble spots will remain unaddressed. Note: If you address the trouble spots before singing the anthem all the way through, I can almost certainly guarantee you that most of your singers will get into the music and will forget your instructions by the time they get to the critical point.

So you must work in small sections, usually of several measures to a couple of pages in length. If you do this, you’ll be well able to obey “repetitions are essential” because you’ll be able to sing each passage lots of times. You’ll also be able to play with the “technical combinatorics” (i.e. how different technical aspects interact and combine) in each passage. And your choir will love you for it because they’ll know that they’re making the kind of progress you wish for them.

There’s an important note with respect to contrapuntal works, such as those by Bach or Mendelssohn: Allow for slop. The fact of the matter is that you’ll have a hard time finding convenient starting/stopping points in these pieces as the musical lines interlace. So you must choose key sections as the focus of your work for the evening – and then you should allow for a little “fade-in” as you start and the vocal sections find their entries (and if you have a choir which will jump right into the music wherever you start even under these circumstances, the more power to you).

Guiding Principle II: Isolate technical aspects as required.

As the first guiding principle claims, the most effective way to work on anything is to break it into pieces which can be solved separately, then to integrate the individual solutions to form the answer to the whole problem. The best way to accomplish this in a musical setting is to separate individual technical aspects from each other before attempting them in combination. There as many number of ways to approach this as your imagination can produce, but here are a few ideas which I’ve used with uniform success:

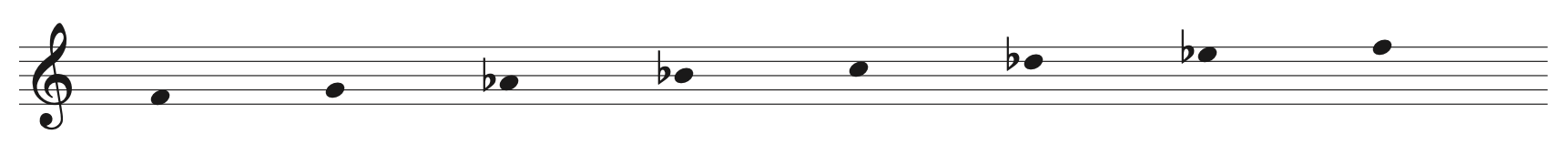

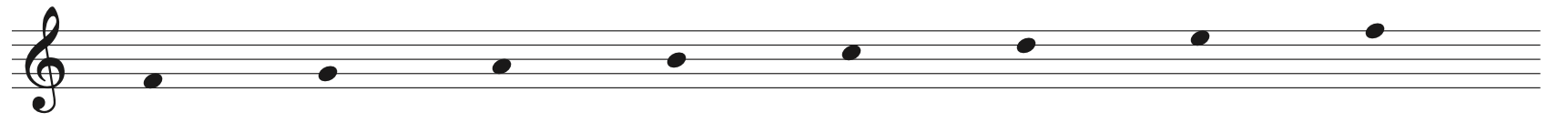

To isolate intonation:

Work pitches “on the stick.” Have the choir follow you as you hold each chord to verify the pitches. This is very effective in homophonic passages (places where everyone has the same rhythm) because you can work on the blend of individual chords as well as the intervals each section must sing to negotiate the corresponding chord transitions. Within this technique is the idea that you can hold a single chord for awhile and adjust section pitches to improve the acoustic mix of parts and timbre.

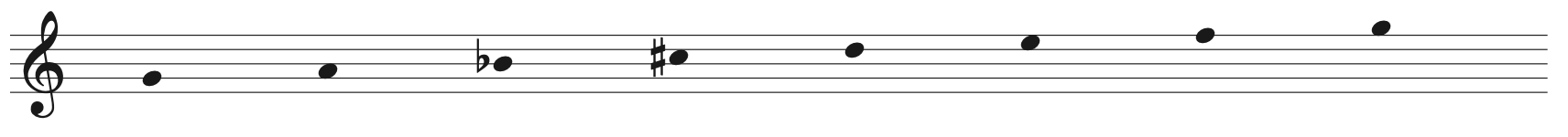

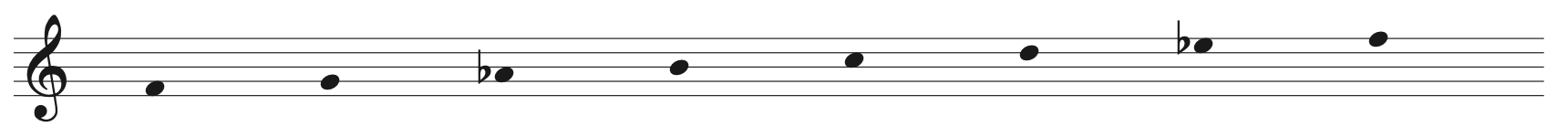

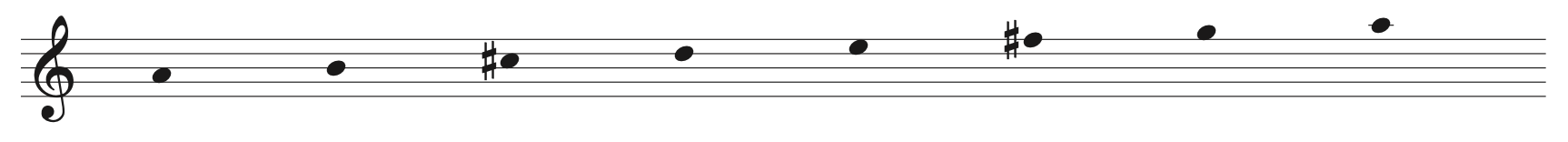

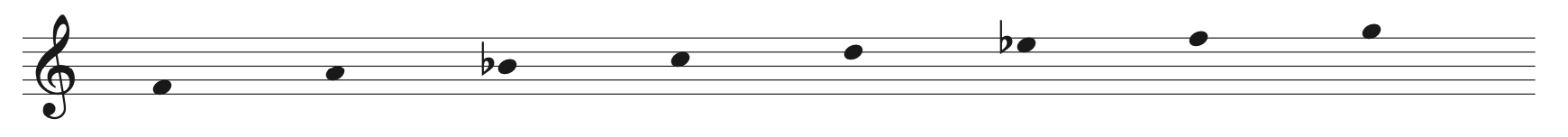

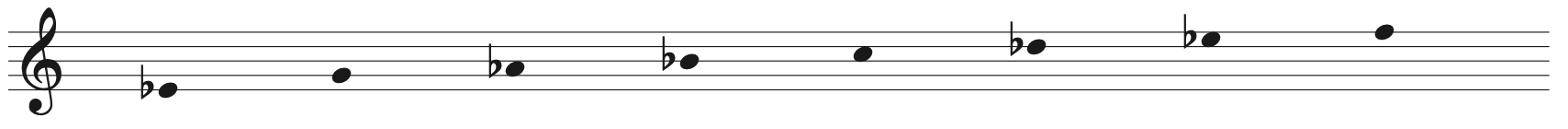

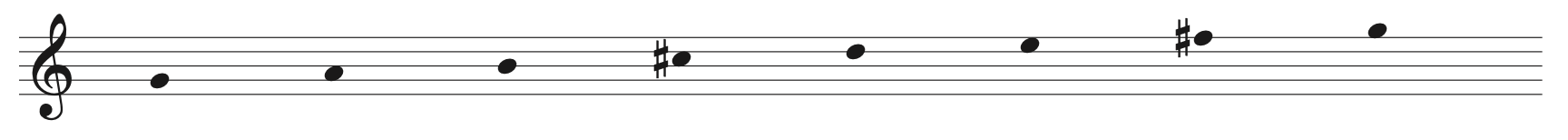

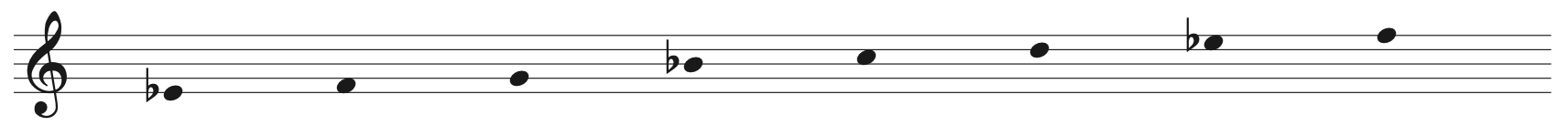

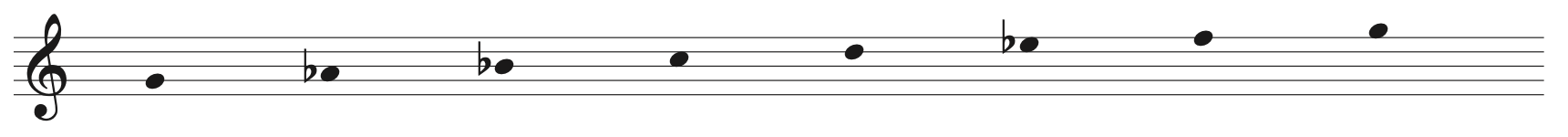

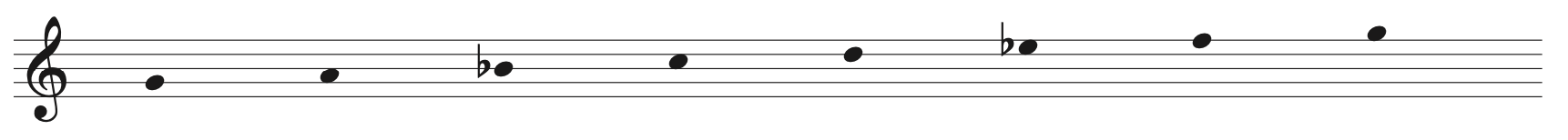

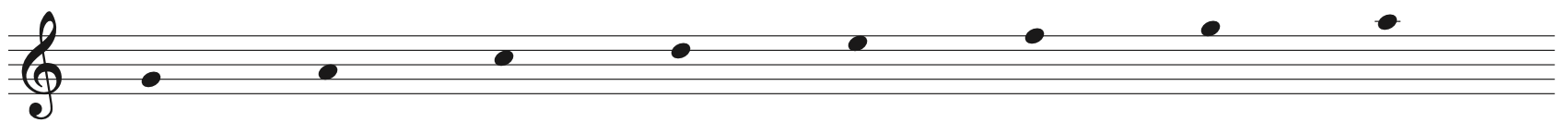

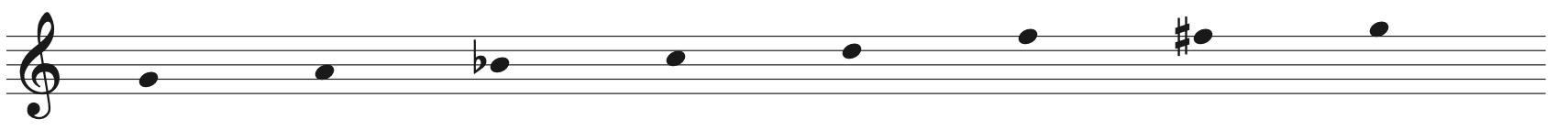

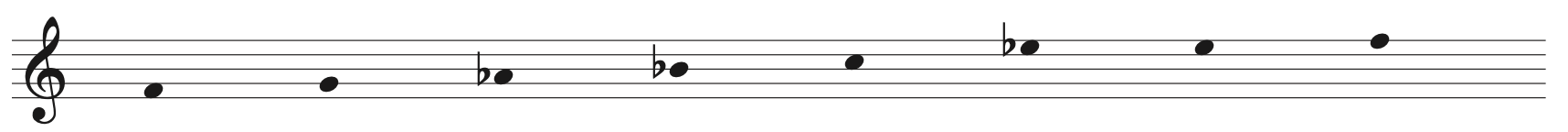

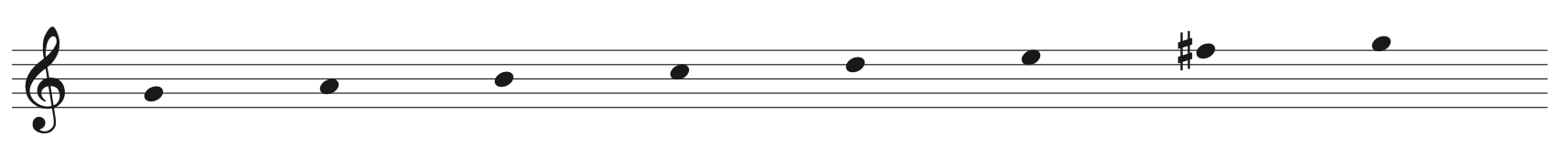

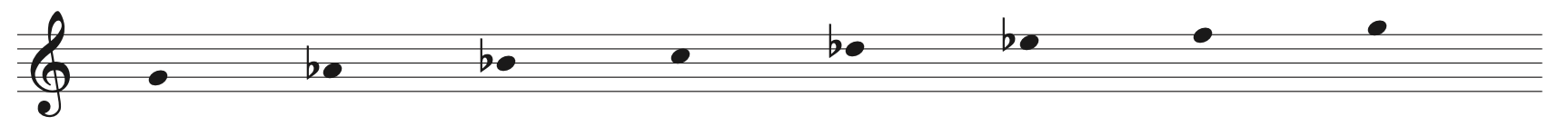

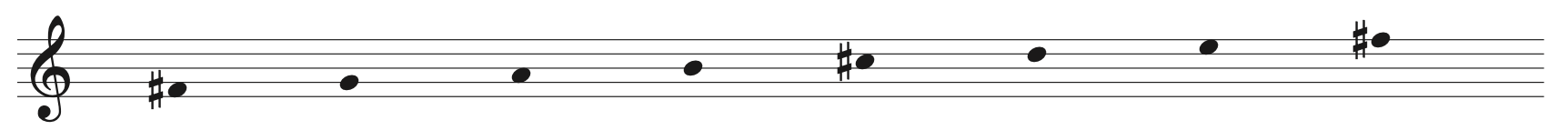

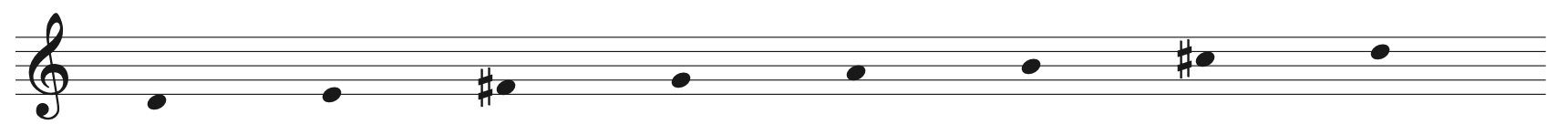

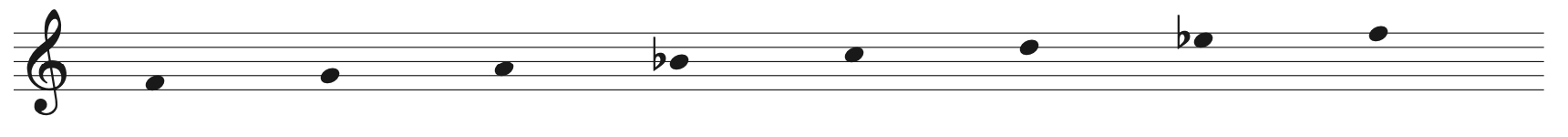

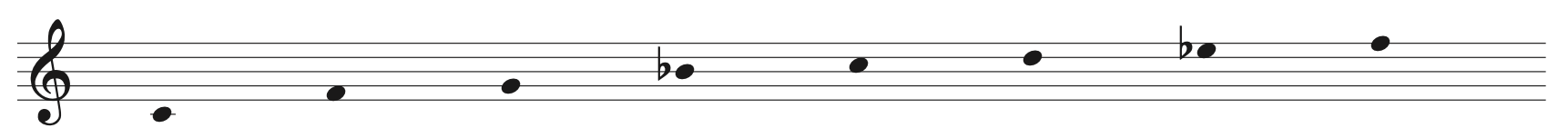

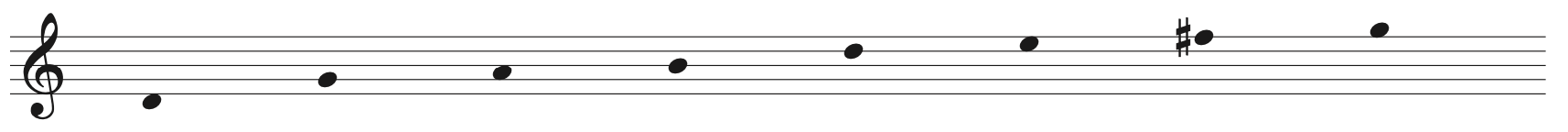

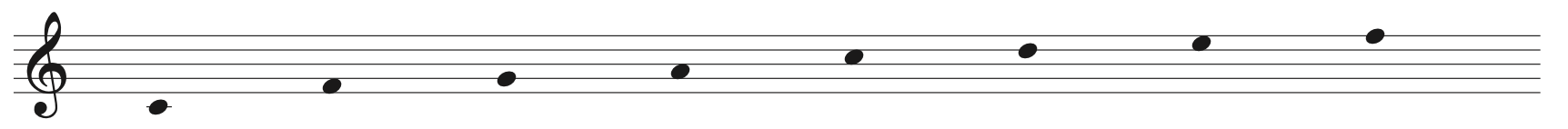

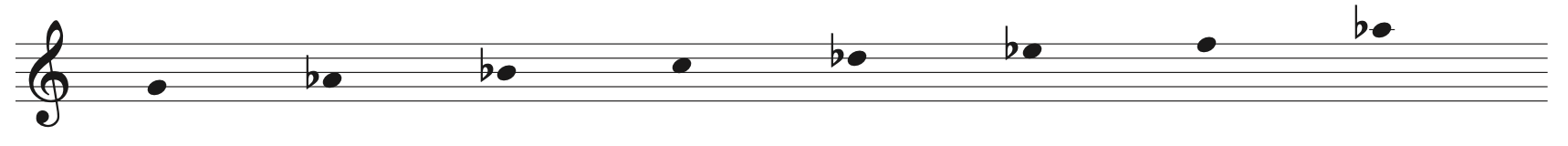

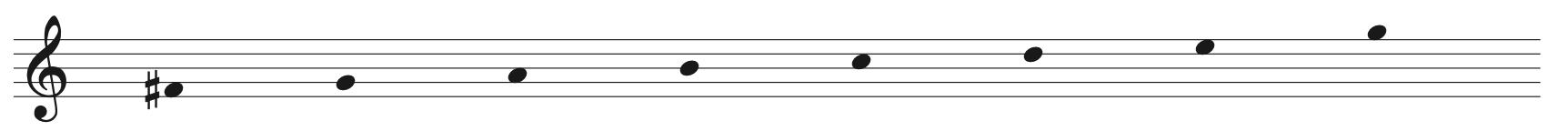

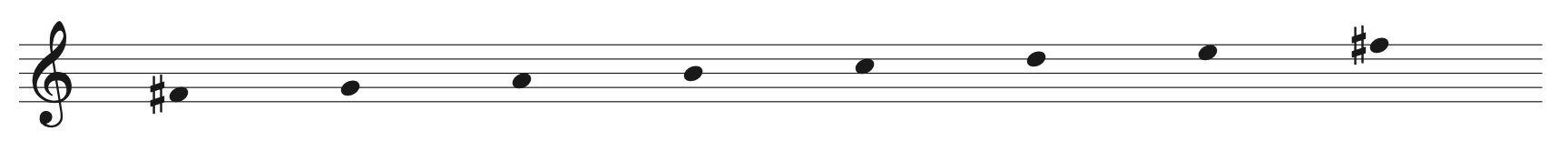

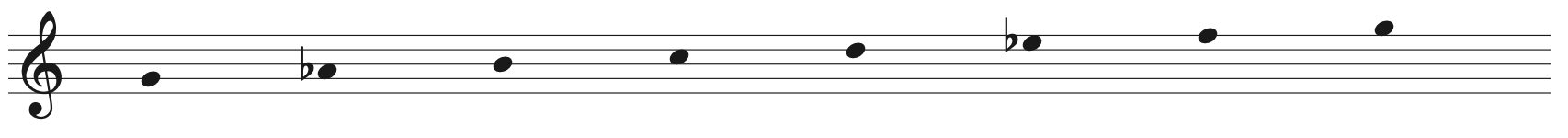

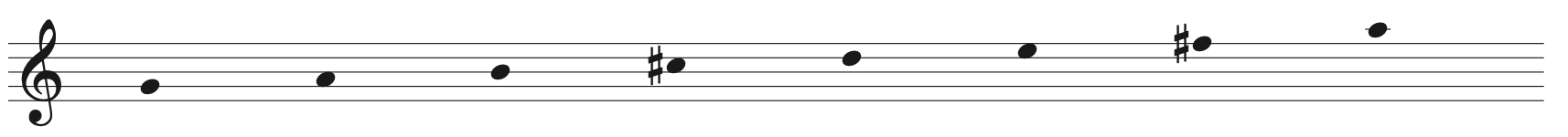

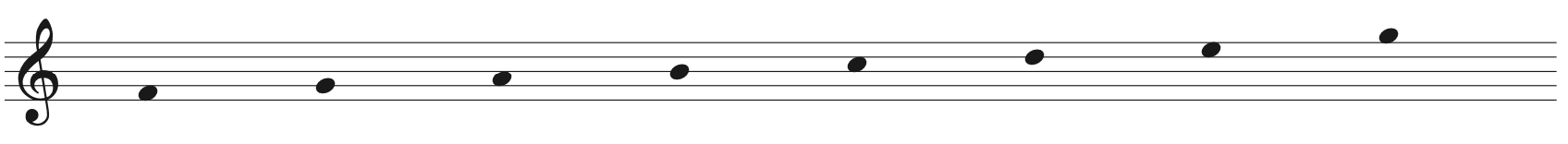

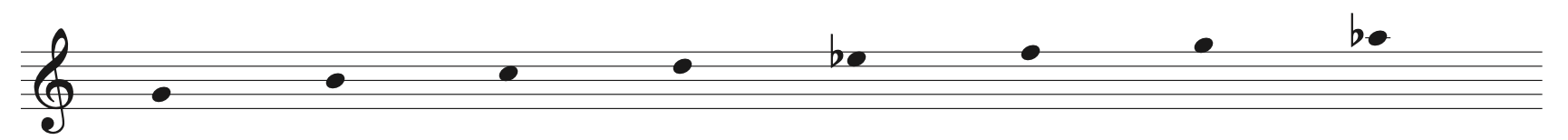

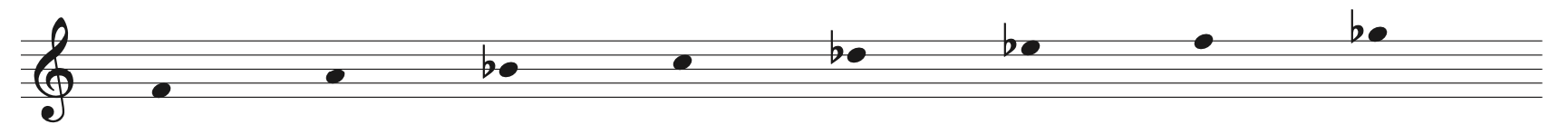

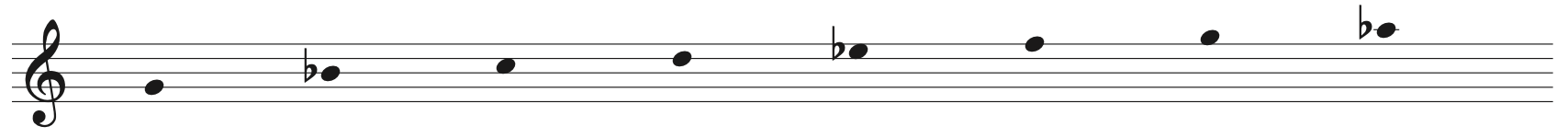

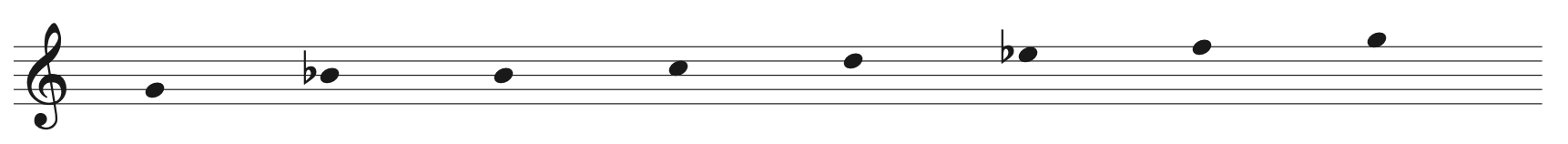

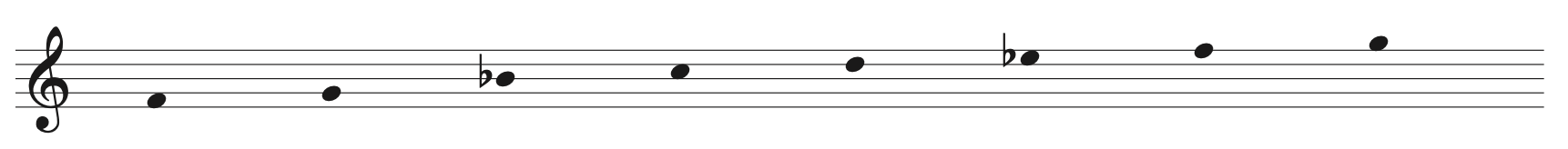

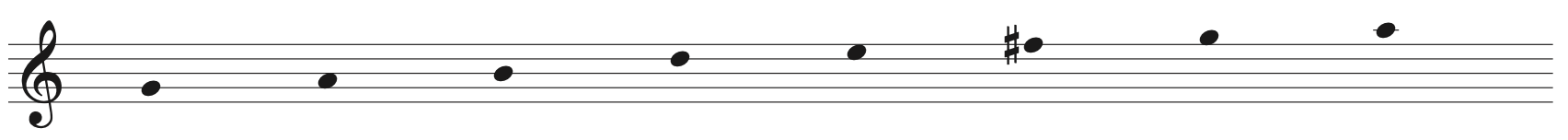

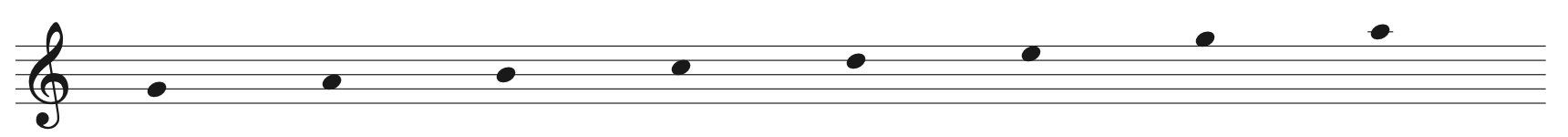

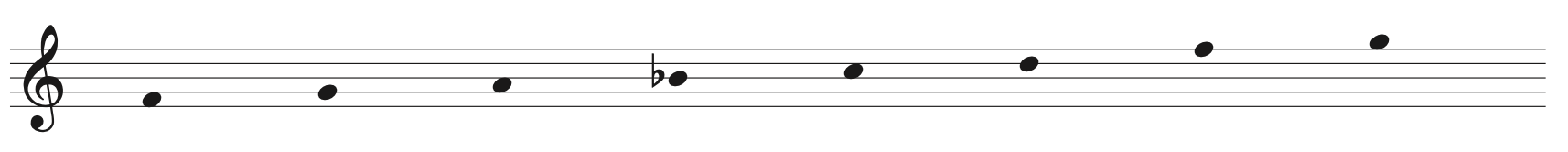

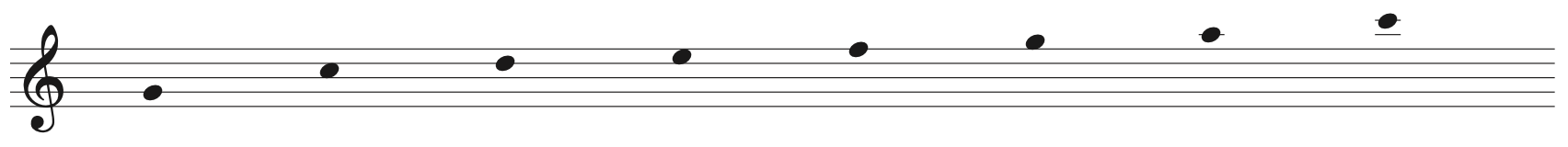

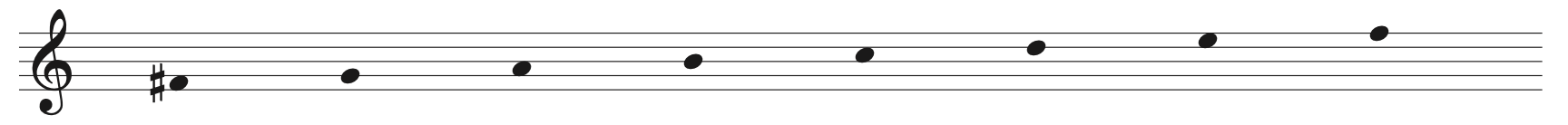

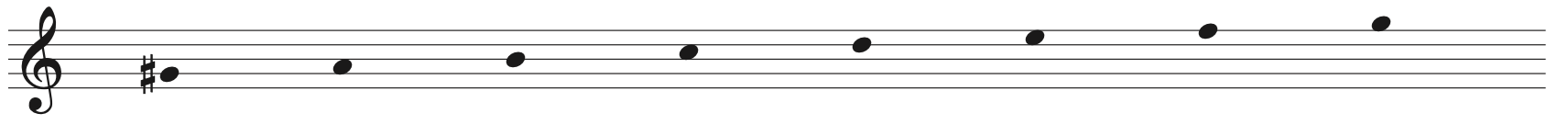

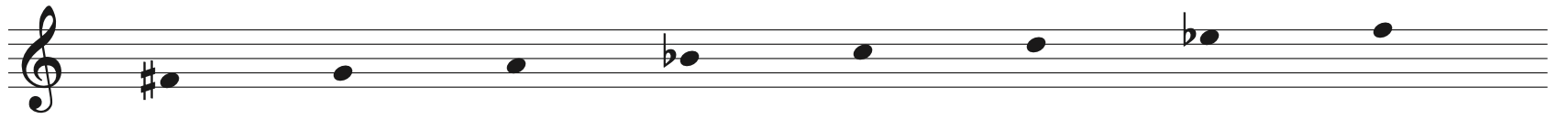

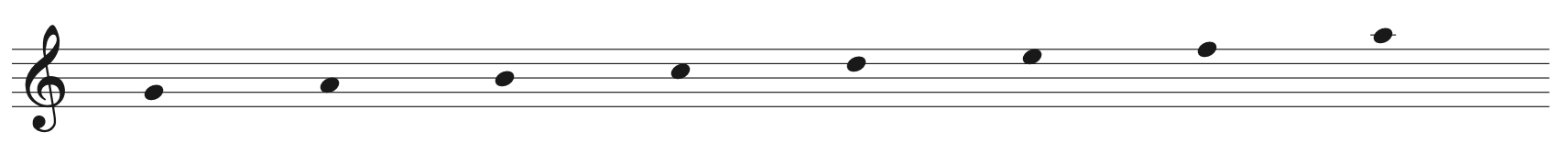

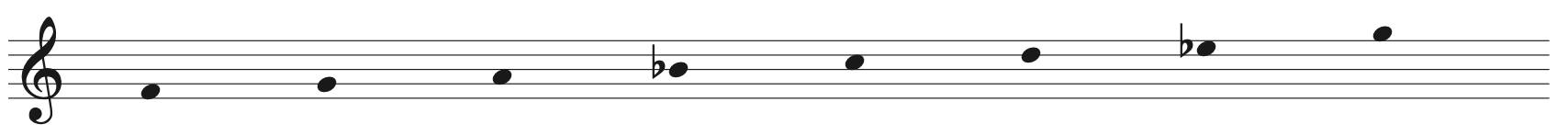

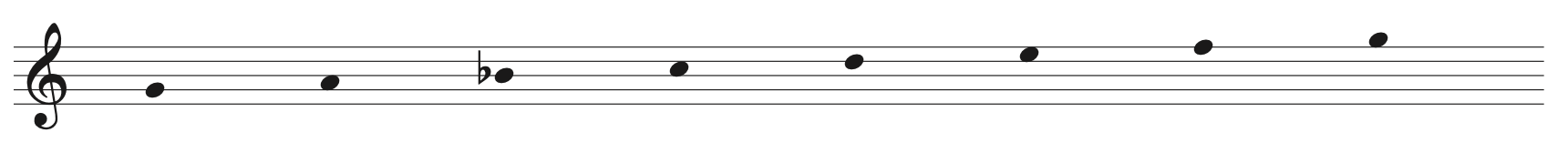

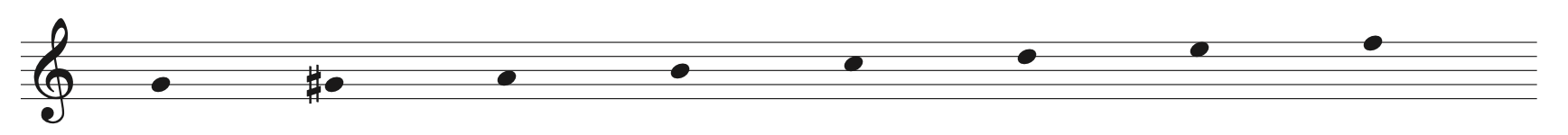

Use transposition as a rehearsal tool. If a passage just isn’t working, the problem might be the written key – sometimes the tonality of the anthem puts more than a few notes right on the vocalists’ tessitura (“register”) breaks, making the music difficult to sing. You can start from a lower key to learn the intervallic relationships in the musical lines, then reintroduce the written key later. Alternatively, you can just leave the music transposed (assuming your accompanist is comfortable with this).

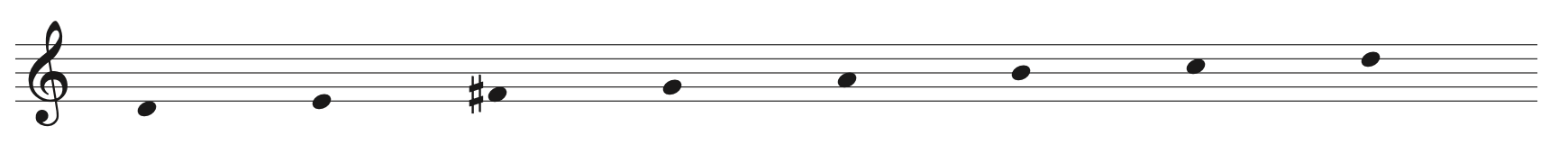

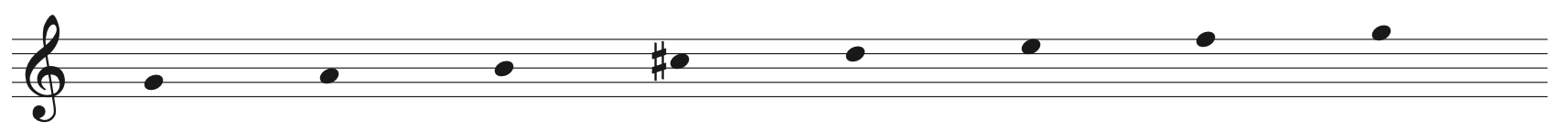

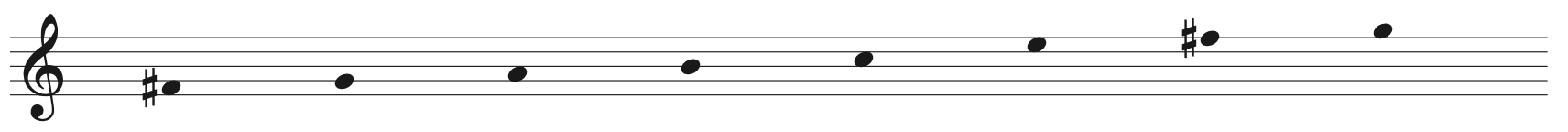

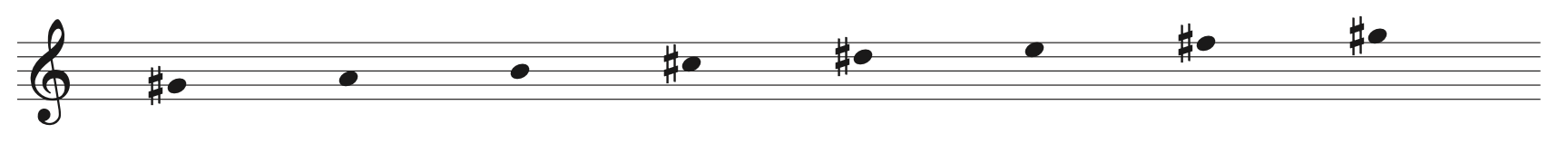

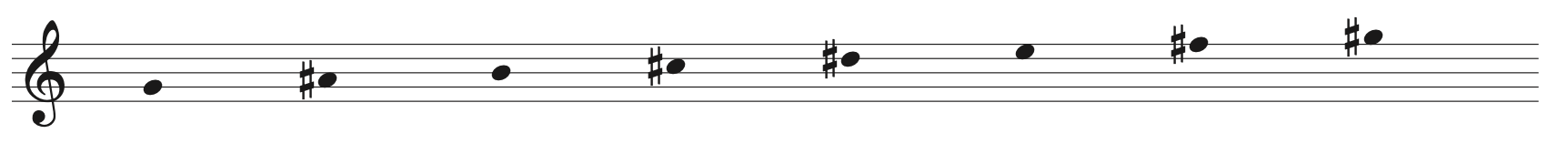

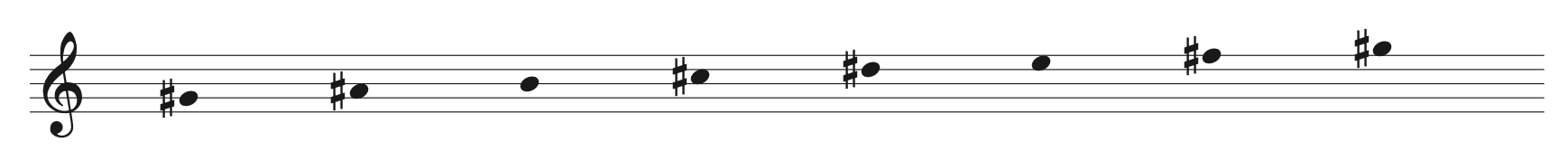

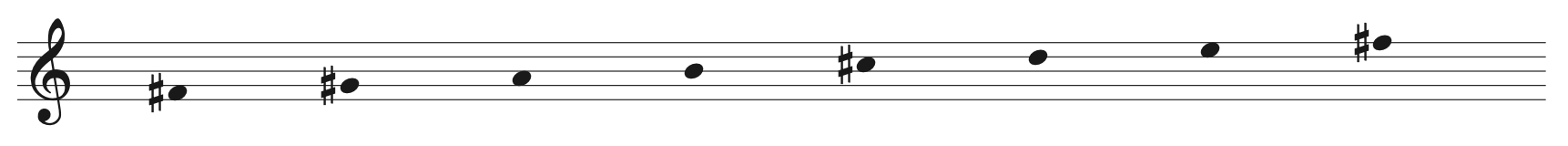

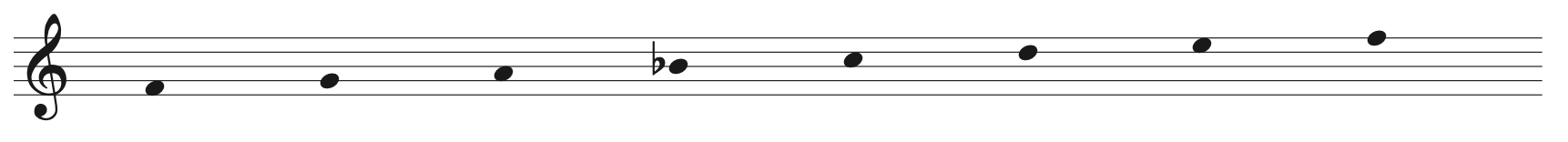

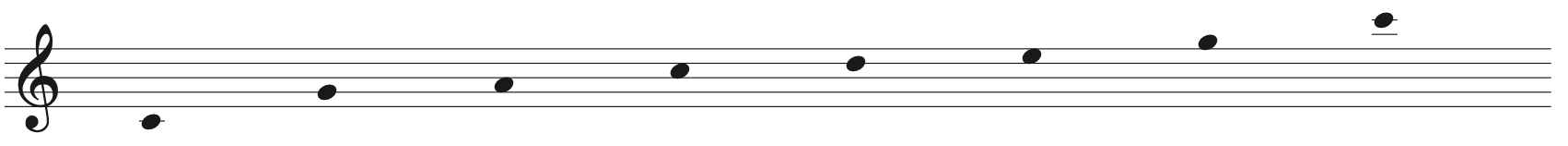

Take time to learn large intervals. I guarantee you that if you don’t do this, you’ll have scooping and sliding as people attempt to sing intervals which they haven’t learned well enough. Here are some ideas which may be useful:

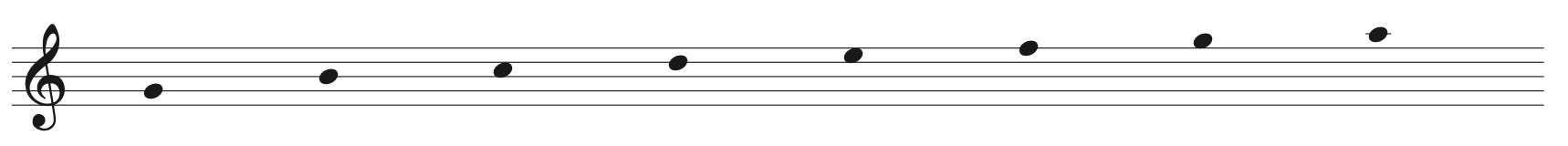

Learn the intervals “on the stick,” or at least below written tempo. You shouldn’t be taking the music any faster than the fastest tempo at which you can sing it correctly! Have patience, and this initial time investment will pay handsome dividends.

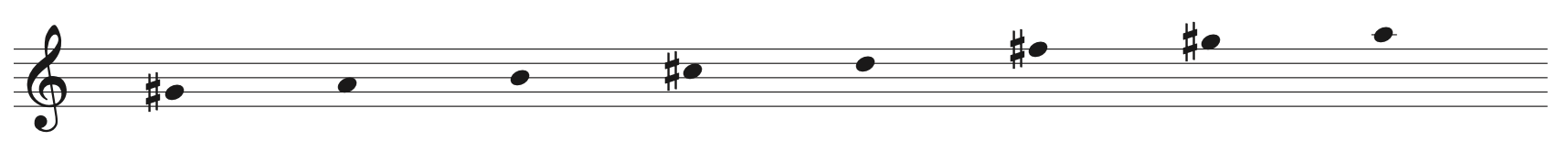

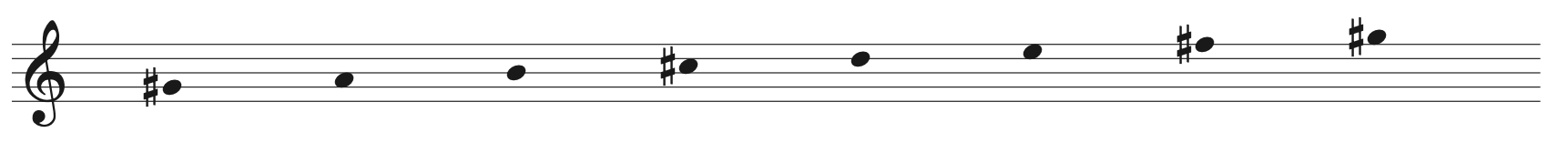

Sing only as loudly as you can hit pitch correctly. Sometimes intonation problems on large intervals are a result of people trying for too much volume (notably, I’ve found this to be true particularly with tenors on high F# and sopranos on many notes above high F). Remind them to sing no stronger than the maximum volume at which they can maintain the correct pitch.

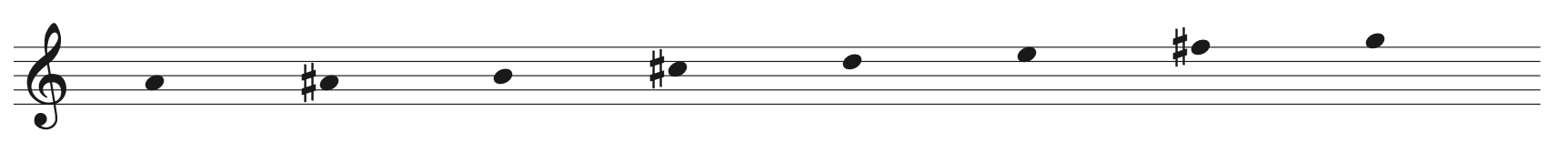

Use (unvoiced) consonants to avoid sliding between pitches. Sometimes pitch problems are due to having voiced consonants (e.g. “d”, “g”, “b”, “m”) between pitches. Voiced consonants can throw intonation out of kilter because they have a pitch of their own and involve a different vocal apparatus configuration than the adjoining vowels. The difficult solution to this problem is to ensure that every singer can transition between pitched consonants and vowels accurately. However, there’s a far easier solution: Just have everyone sing the unvoiced form of the voiced consonants (“harden the consonants” is another expression I use); for example:

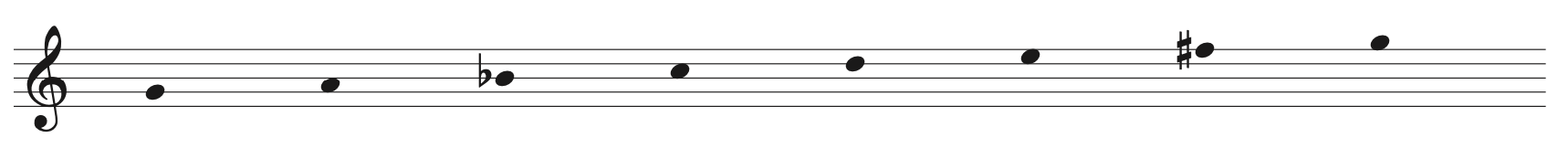

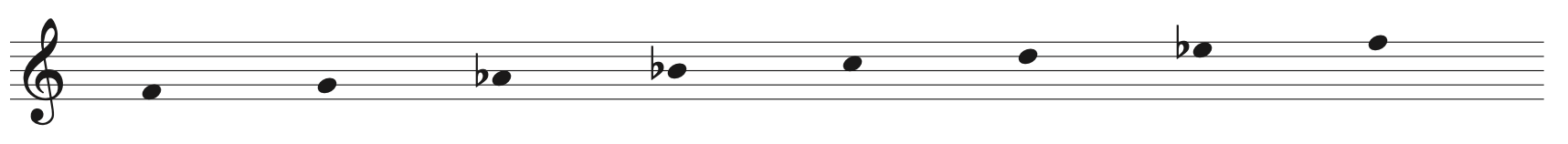

“b” becomes “p” “z” becomes “s” “d” becomes “t” “g” becomes “k”

(and so on).

Initiate breath support before singing, and maintain it until well after cutoffs. Failure to support in time is a reason for many initial “scoops,” and failure to continue breath support (but not sound!) into rests is a reason for flatting at the end of phrases.

Think the pitch before you sing it. This, perhaps, is the soundest technical advice you can give with respect to intonation because mental disposition affects everything else.

“Relax into pitches”: This is an important key to proper intonation because singing ultimately must sound completely natural. To reach this point, you must relax! By this, I don’t mean to ignore all muscular control; I’m just saying that having a choir which is permeated with tension and stiffness is the other extreme of poor quality. I remind my choir of this frequently, especially on passages which go to high pitches or which have large intervals.

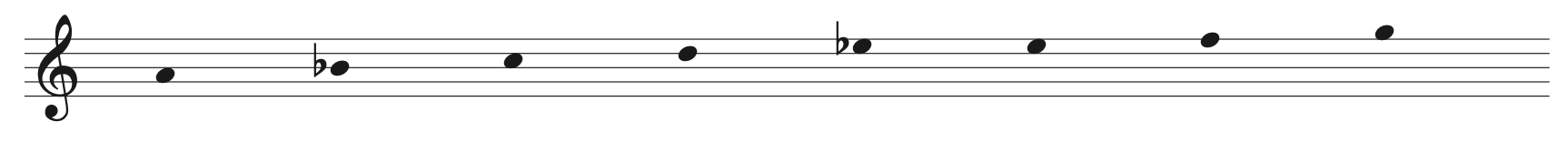

To isolate rhythm:

Clap in time: Clapping the rhythm of a passage frequently reveals rhythmic inaccuracies on the part of even one person. It’s a little embarrassing to be the one who’s out of sync, but as long as you, the director, remind everyone of the purpose of the exercise – to find and fix problems rather than to pillory those who make errors – your singer should take it well. Remember to address this with a careful bit of humor too (“If you learn to laugh at yourself, you’ll never run out of material”).

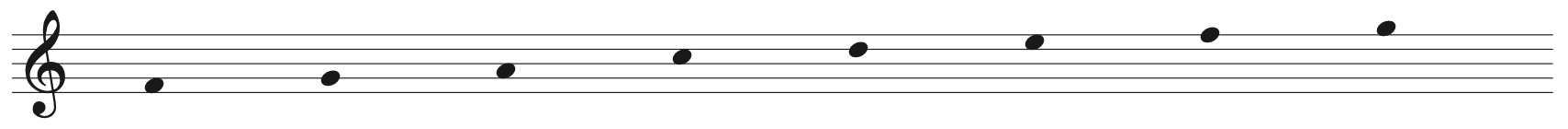

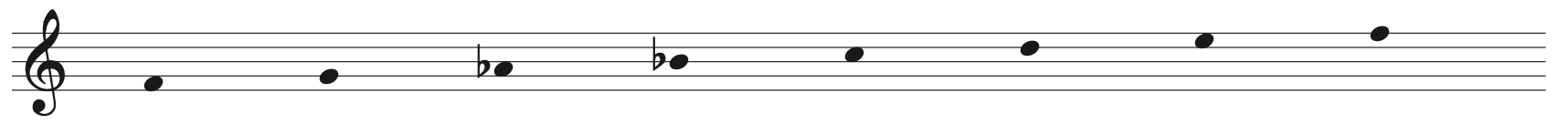

Use beat subdivision: Rather difficult rhythms can be made more understandable by subdividing them into the longest time value which evenly divides all the notes. What that last long sentence meant was that if you can find a “unit note” by which the music can be counted, you can use it to analyze a rhythmic pattern. Some ways to do this are:

Count the pattern according to the time signature (e.g. if the unit note is an eighth note in 4/4, count the notes using “1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and …”).

Sing a single syllable on the unit note, accenting the ones which begin notes as written in the score. For instance, quarter notes in 3/4 would be counted using an eighth note unit thus: “ta ta ta ta ta ta.” If you use this method, I recommend that you choose a syllable with a hard consonant (“ta,” “pa”) so that you can know easily whether everyone is starting their pitches at the same time.

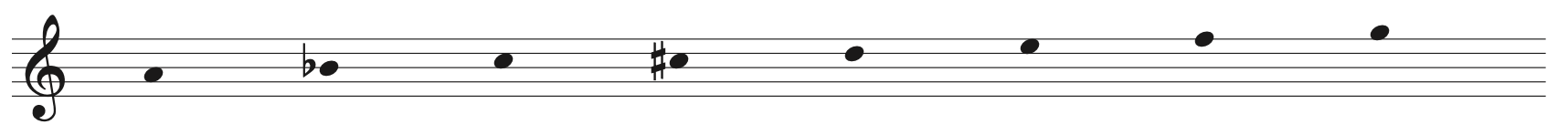

“Perturbation theory:” Okay, I borrowed this terminology from quantum physics, but the general principle is the same. The idea is to start from something which is familiar and close to what you want to achieve, then to change it (gradually?) to what you want as an end result. For instance, a dotted eighth-dotted eighth-eighth rhythm can be treated as a mild time distortion of eight note triplets.

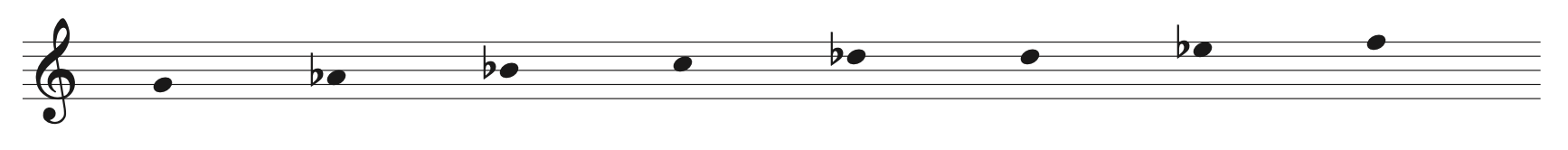

To isolate diction:

Work individual words or even phonemes: Diction as a whole can’t be correct or clear until you’ve worked out the smallest elements. One person pronouncing one vowel or consonant incorrectly (perhaps read “differently”) can affect the blend or diction of the whole group. In some sense, it’s more important to ensure that everyone is using the same diction, but in this context it also is essential that the dictional patterns used make the text understandable.

Explain dictional requirements of text: Often I find that problems with diction are attributable to a very few general technical difficulties, so I occasionally will take a few minutes during rehearsal to explain the dictional concepts involved, followed by some work with them. The bottom line is that sometimes you just have to take the time to explain things so that you can guarantee that everyone’s on the same page – and I realize that while this may rankle some of the “talk little, sing much” types, I endorse this practice if it’s used with wisdom simply because it saves so much heartburn over the long haul.

“BTTTT” as required: BTTTT is the notation I put on my rehearsal notes to indicate “Below Tempo, Then To Tempo.” It means that I’m planning to work a passage slowly (until we get it right), followed by resinging it at gradually increasing tempo until we’re up to whatever the score says the tempo should be. Often I’ll work significantly beyond tempo, especially on passages demanding dictional clarity over rapid syllables; if we can sing the passage faster than required, we certainly can handle the diction at tempo. Just so you know, I’ve worked with my choir up into the 300-syllable-per-minute range on occasion with this approach.

Balance dictional elements (particularly sibilants) properly: Sometimes it also is necessary to ensure that the consonants and vowels are in proportion to each other. For instance, I sometimes find it necessary to remind everyone to lower the intensity on their “S”‘s so that the rest of the text isn’t damaged.

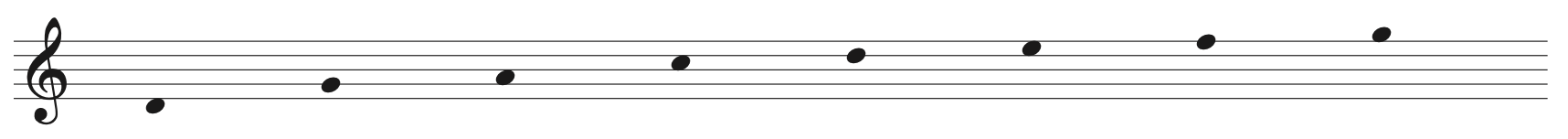

To isolate timbre:

“Resonance center” and placement: I imagine that everyone has their very own way of teaching about vocal production and timbre… My way is to present the concept of a “resonance center.” It’s where the sound of your voice is focused. Nominally, the resonance center should be at “middle position,” that is, centered between both cheeks and halfway between the tongue and palate. From here, you can adjust timbre by having the whole choir (or even individual voices) move their resonance centers.

Example: One time we had a section of an anthem where there was a soprano-alto harmony duet above a men’s unison melody; both parts also had somewhat different rhythms. Because it was difficult to hear the men’s melody, I had the tenors and basses move their resonance centers downward slightly and had the sopranos and altos move their resonance centers upward slightly (about an eight of an inch in both cases). The result was two timbres sufficiently different to hear both parts, but close enough to each other so that the parts also blended. The general concept is to match timbre to unify, and mismatch (almost always only slightly!) to distinguish.

Matching timbre with other people: People usually respond very well to a descriptive approach (as long as the description is understandable!). Often you’ll have one singer whose voice closely matches the sound you want from the whole section or even the whole choir, so try telling everyone involved to sing “like (fill in the lucky person’s name).” Here’s a time when knowing the voices that you lead is very, very useful: You can even accomplish this adjustment by appointing one person in each section to be the “key voice;” another alternative which works well is to have the tenors sing their written notes as if they’re basses, and to have the basses sing their written notes as if they’re tenors – and all of a sudden, your intersectional blend will usually improve!

Guiding Principle III: Integrate the technical aspects

Once you’ve dealt with the individual technical aspects, you need to reintegrate them into the whole choral expression. I suspect that many directors tend to go straight from the “single-concept-isolation” phase to doing everything at once; this works well with excellent choirs, but can be rather difficult for less skilled/experienced people. So it’s important to have a few wayside stops between the two ends of the process.

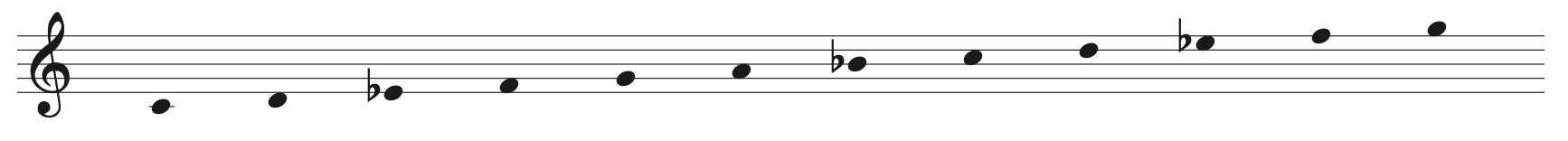

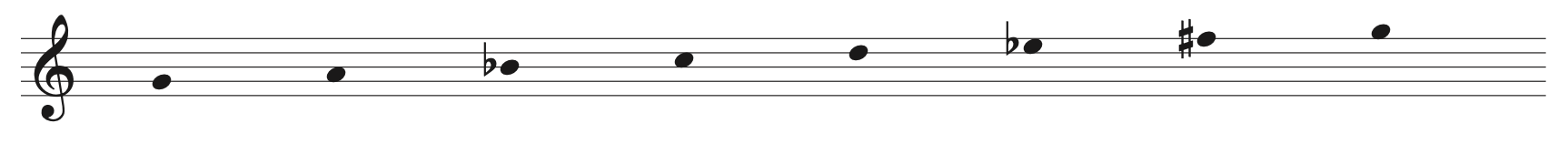

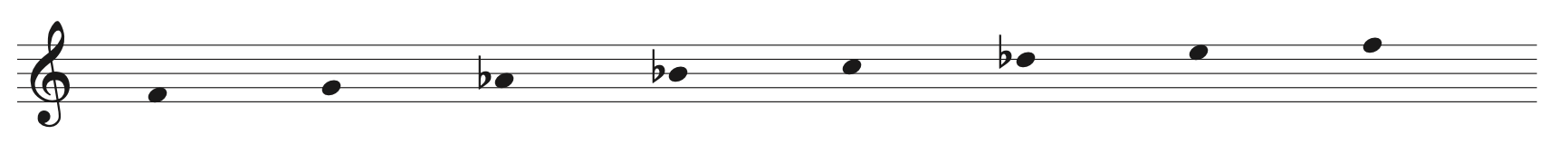

Integrate intonation and diction: The reason it’s important to integrate intonation and diction is that some of the consonants are voiced (B, D, and Z, for instance). It turns out that singing a voiced consonant next to a vowel tends to produce a pitch change because the level of breath support changes when opening or closing the mouth. There are a couple of ways to deal with this:

Control the pitch of the voiced consonants (difficult): This involves being cognizant of the consonant pitches as well as the vowel pitches around them. The bottom line is that this approach requires exceptional control of breath support, and takes a long time to learn.

Substitute unvoiced consonants for voiced consonants: For instance, you can sing T instead of D, K instead of (hard) G, and P instead of B. The obvious first effect is to circumvent the diction-pitch problem by separating diction from intonation. And while you might think this will make the text sound weird, this is not the case: It turns out that the very, very slight dictional imprecision (on the order of a few milliseconds) which exists between individual singers in even the best choirs serves to lengthen the consonants without voicing them – and so the congregation hears the voiced consonant and never knows the difference!

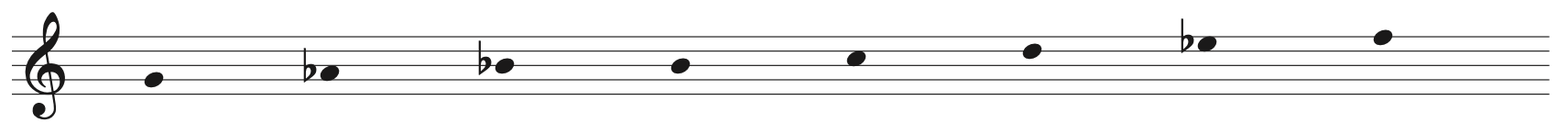

In the same breath, use unvoiced consonants to negotiate large intervals. The problem with large intervals is that they require a lot of muscle coordination, hence the scoops and slides which we hear with some frequency. Believe it or not, all you have to do is have everyone use unvoiced consonants rather then voiced one at the junction between notes, and you’ll have this one licked (note: If there isn’t any consonant between the syllables, use a tiny (H) to accomplish this!

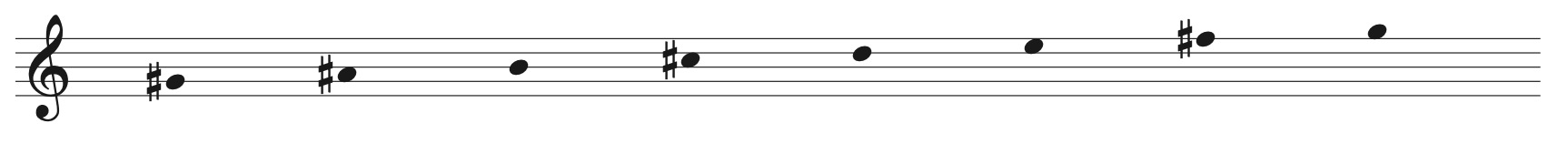

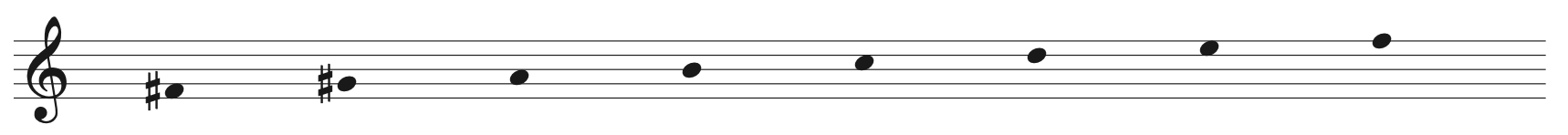

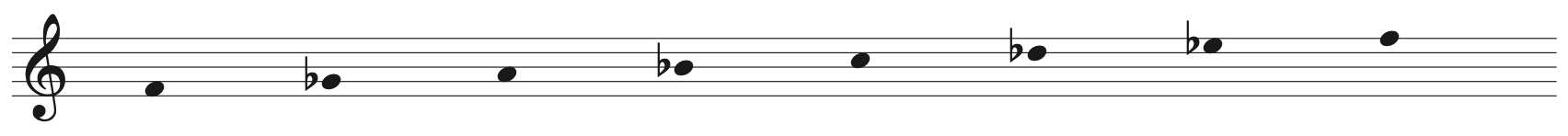

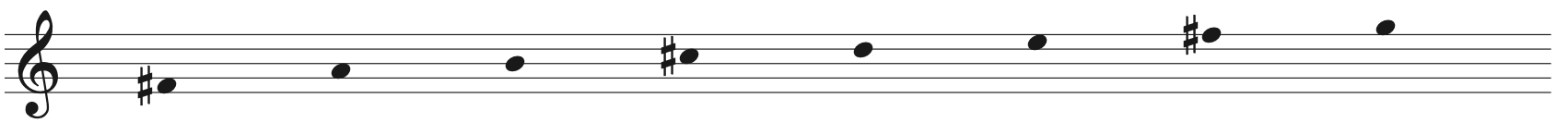

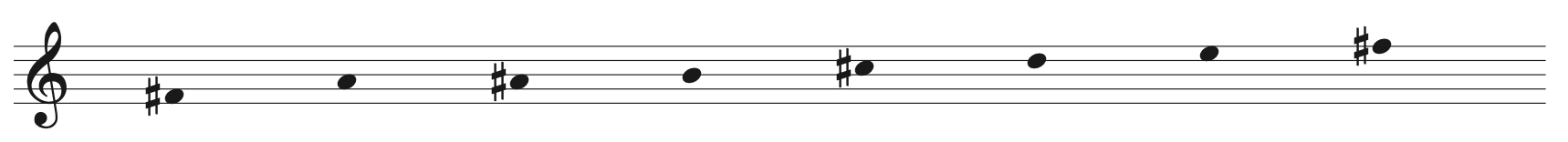

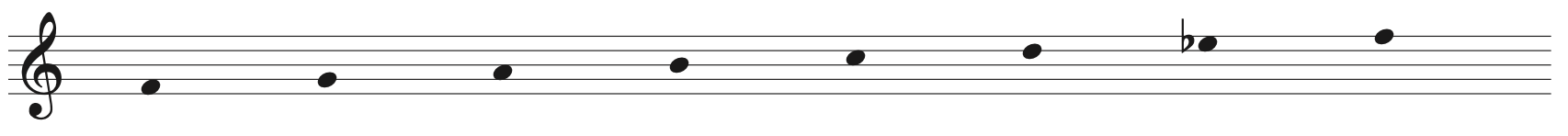

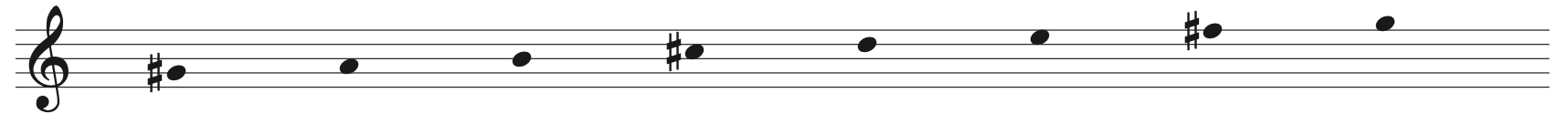

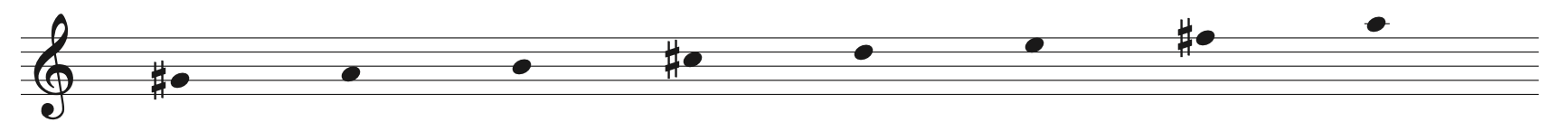

Integrate intonation and timbre: Integrating intonation and timbre occasionally is difficult simply because the vocalist’s ability to maintain pitch control changes with tessitura. This is particularly true of the “break points” between ranges; for most people, the first major voice break is around high Eb; I also find that I shift registers at Ab above that, and at C# above that.

Aside from the voice breaks, another minor subtlety is that a singer’s timbre also changes within each register. Physics explains this more than adequately, as what you hear is a combination of natural vibrational characteristics, musculoskeletal configuration, and surroundings. For instance, I think my own voice sounds better in an old chapel with lots of reverberation, which actually means that I can still sound like I know what I’m doing even when the same sound production in a “dry” room might sound trashy.

Here are some ideas you can use in the choral setting:

Balance intonation and timbre. You need to be in tune and to have a vocal tone quality appropriate to the music you’re singing. However, individuals have limitations, and so you need to compensate for them. A key concept here is to remind everyone not to sing outside their abilities (well, unless the music calls for it, which occasionally will happen). Some directors use the idea of maintaining a “covered” tone to keep intonation and timbre under control; my analogy for this is to remind everyone to “sit on the notes,” which implies that they’re reaching down to get them rather than straining upward.

Balance individual chords (separately). During rehearsal, you can tune individual chords by “freezing” on them one at a time. You just can’t evaluate the blend of a chord unless you take the time to listen to it! I find this to be particularly effective when I finish a phrase and have my singers freeze on the first note of the next phrase – in addition to improving intonation, it also improves their entries.

There’s another side benefit to this: If you direct the music off-tempo (for instance, using one motion per note/beat with subsidiary cues for moving lines), you’ll also get your choir in the habit of watching you. And subconsciously, they probably will also develop an understanding of which chords are most important to you.

Account for uniqueness of your ensemble’s voice combination. Unless you’re one of the very privileged few, you just don’t have a Shaw Chorale or Mormon Tabernacle Choir in front of you. Most of you probably have ten or fifteen singers. But don’t worry about the other directors: God has given you a very special musical family in that choir. You work together, play together (what? you don’t? shame on you! get out there and have dinner together!), and in some sense you even live and die together – at least figuratively in performances.

Part of your job as the director is to learn the individual voices in your group. My best, most memorable, most wonderful performances are those in which I sense that I have enough control of what we’re doing (and everyone is paying attention closely enough) not to the point where I can adjust the volume or timbre of each section as necessary, but so much contact and communication that I know exactly which single voice needs to be adjusted to make things sound “just so” – and can make those adjustments (there’ll be a whole section nonverbal signals later on…).

Encourage awareness of other voices. Bottom line: No matter how skilled you become, and no matter how skilled each singer becomes, you can’t do anything up to potential unless you’re all listening to each other (what an illustration of I Corinthians 12-14 – you and your choir are an object lesson for the congregation every week!). So you need to encourage everyone to listen to what’s happening around them, and to understand the context in which they’re ministering.

Here are a few ideas you can use to build this habit (and mark my words, you shouldn’t be satisfied about this until it really is a habit):

Have singers impersonate each other’s voices. But remind everyone that it’s all in fun, and that it’s okay to laugh at yourself. This could a hilarious experience… but be sensitive to those who aren’t as used to having fun as you are…

Remind them to listen to each other. This, too, must become a habit! Also, remind them that blend works best when you make your timbre the average of the timbres around you.

Reconfigure the choir. Move the sections around, or have everyone stand in a circle and sing to each other, or have everyone mix up, or configure in quartets and sing that way. The idea is to help everyone get used to singing anywhere, anytime (and if you have an extra dose of bravery, you might even try having everyone sing a part other than their own…).

Integrate rhythm and diction: The key concept here is that consonants and vowels define rhythm. They mark the beginnings and endings of notes, and therefore must be placed precisely.Vowels start when the note does. It turns out that our perception of words and their timing is based on when we hear the vowels: If the vowels starts after the note in the score, the word is perceived as being late. So this means that the leading consonant must be pronounced just ahead of the note.

If no initial consonant, use (H). Singing a vowel by itself generally has a bit of a “fade-in” effect because you’re trying to generate breath support while your throat and mouth are open. The breath support must be there for a solid attack! I tell my singers to use (H), a glottal stop – not a pronounced consonant – to build support before they release and sing the leading vowel. Incidentally, this also will help maintain proper intonation because it guarantees consistent breath support.

Vowels end when the note does… At the end of a phrase, place the final consonant where the rest after the phrase starts. If there’s no terminal consonant, use (H) – which, once again, is more of a diaphragmatic punch than an actual consonant.

… well, sort of. In the middle of a phrase, however, you can’t place terminal consonants after the note and initial consonants before the note because the words will overlap! The compromise which virtually all directors endorse is placing the consonants between vowels before the next note. Most directors will also teach that terminal consonants before initial consonants should be blended together – I add my own refinement to this by stating that this is acceptable if the meaning of the text is clear. If not, separate the consonants with a very quick (H). An example of where this is important is the lyric “Friends come and go…” (the proof is left as an exercise for the student…).

“Sing” only consonants. This is a method which my friend Doug Lawrence uses on occasion. It’s a little hard, but it really does work if you can learn to do it.

And that’s pretty much it in terms of integrating technical aspects unless you want to integrate three or more aspects at once (tough to do, great if you can manage it). I haven’t yet found a good way to integrate intonation and rhythm or rhythm and timbre – if you come up with something let me know…

Guiding Principle IV: Allow enough time.

People, you and me included, take some amount of time to learn everything we undertake. This means that your choir is no exception, so you need to be humane and understanding of them by giving them time to absorb what you’re teaching them. You must allow for the following to develop:

Mental understanding: They’ll need to comprehend what exactly you want them to do as they sing, so you have to communicate this. Even more, you have to communicate so that they understand and even endorse what you’re teaching. As any teacher will tell you, this is usually a dicey proposition at best…

I usually approach this sort of thing using an “explain and do” approach; I’ll explain the concept and then have everyone put it to work. For instance, we were once having some difficulty with a “J” followed by a rather jump upward. This problem generally manifests itself as a pitch distortion, usually as a “scoop” up to the note after “J”. So I asked the choir to pronounce the “J” more like a “CH”, and immediately had them sing the passage – and the problem was solved.

A word to the wise: The principle of “talk little, sing much” is very, very valid! Keep the explanations brief, and give them time to learn and experience the music. If there are many issues you want to tackle, tackle them one at a time; work them separately so that your choir’s mental focus is unimpeded. If I have several things to do in a single passage, I’ll start with one and add the others incrementally as they master each technical point.

Muscle memory: Singing is a muscular endeavor which involves the whole body, so you must provide for everyone to get a (fairly large) number of repetitions on each part of the music. The idea is to embed the song in muscle memory so that it’s natural and free.

This means that you’ll need more repetitions on some passages than others, so do them! Don’t just sing through everything once and leave it at that. Your choir can be much, much better for having gotten solid practice and education as they sing together… so don’t deny them this and they’ll love you for it!

“Second nature”: You want to build a musical experience which will demonstrate the life of Christ in your choir and its ministry, so ideally, you’ll want to learn each song until singing it becomes second nature. This means:

You need to allow for everyone to learn the music. Provide them the repetitions they need and they’ll exceed your expectations every time. Work suitably small passages – even one measure or one chord – before integrating them into the whole.

You should be content to learn part of a song each rehearsal. Learning all the nuances of one song is exhausting and frustrating work. It’s better to learn what you can handle comfortably (no more than about fifteen minutes’ worth of solid work on one song, perhaps) than to push beyond the limits of mentality and patience. For this reason, I’ll work on one verse or a couple of pages of one song and then lay it aside till next week, sometimes without even singing the anthem through.

You need to plan ahead. I’m suggesting that you give each song an adequate amount of time, say, about six weeks at about fifteen minutes per week. For more difficult works, allow eight, ten, or even more weeks (depending on how long you think it’ll take). For easier anthems, you can allow fewer weeks, but I’ve found it’s infinitely safer to start six weeks ahead and skip them for a rehearsal if they’re going well.

An interesting little thought for you “survival mode” fans out there: When you take the “six week approach” to rehearsing songs, you’ll be spending about 90 minutes learning each of them. Funny thing, this is just about the same amount of time you’re spending on the one anthem you learn frantically each Thursday evening… except without the up-tightness and anxiety which you might currently consider to be a way of life.

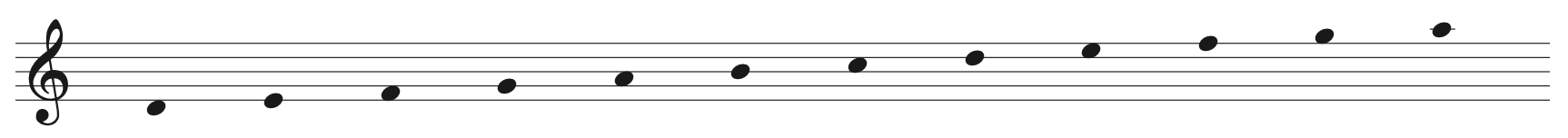

Question: How do I get out of “survival mode”? This is a tough question to answer! It takes a certain amount of time to learn each anthem, and so you might have to make the transition at the expense of somewhat lower quality for the six or eight weeks it takes to make the change. The ideal circumstance would be for your choir to be willing to add fifteen minutes per week for the transition period, to wit (assuming a 90-minute rehearsal:

Week 1:

90 minutes for this week’s anthem

15 minutes for next week’s anthem

Week 2:

75 minutes for this week’s anthem

15 minutes on each of the next two anthems

Week 3:

60 minutes for this week’s anthem

15 minutes on each of the next three anthems

Week 4:

45 minutes for this week’s anthem

15 minutes on each of the next four anthems

Week 5:

30 minutes for this week’s anthem

15 minutes on each of the next five anthems

Week 6:

15 minutes for this week’s anthem

15 minutes on each of the next six anthems

And voila’! You are now out of survival mode! Now you can go back to normal 90-minute practice sessions. But look ahead to Guiding Principle VI: Plan your rehearsals…

Guiding Principle V: Infuse an understanding of “message.

Bottom line: The choral ministry is a teaching/leadership part of worship, and therefore you must – not should, must – communicate the message of your music! Otherwise, the choir is no better than, as the apostle Paul wrote, “a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.”

As Dave, our adult choir director, says, there are about eight or ten different technical aspects we directors must be coordinating / facilitating in every anthem. Let’s see… intonation, timbre, rhythm, breath support, diction, eye contact, volume,… All of these play together as part of the expression of our message, and if we don’t attend to each one properly, the message will suffer.

But it’s not enough to think only of the quantifiable things around our singing. There’s a corporate ethos which much take hold of our choirs so that we can be sensitive to our Lord, our message, our music, each other, and our listeners. We must communicate!

We must understand our message. When I use “message” in this section, I mean the whole choral experience as a medium of communication. If we don’t understand what we’re singing, then we can’t communicate it.

We must believe our message. Insincerity has a way of broadcasting itself clearly. Be sure that you and your choir agree to what you’re singing! and if you don’t, try to iron it out one way or another.

The surest way to avoid this is to be careful in selecting the music you sing, of course. It’s a little embarrassing to have people call out during rehearsal that the anthem you’ve picked isn’t doctrinally accurate. So plan ahead by being very discriminating in your choices.

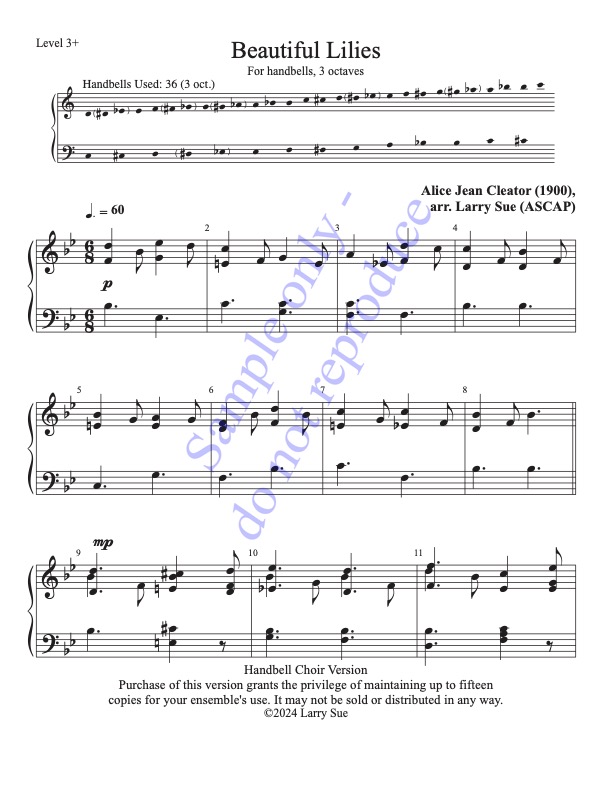

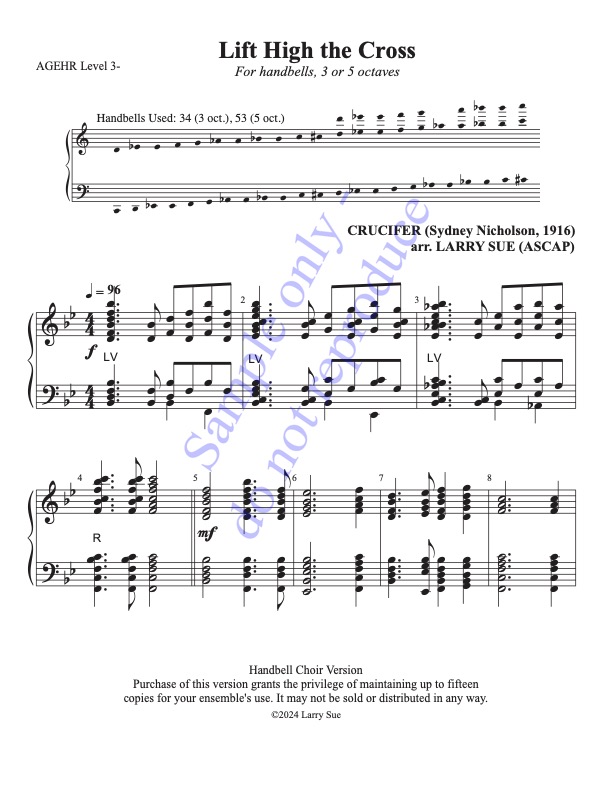

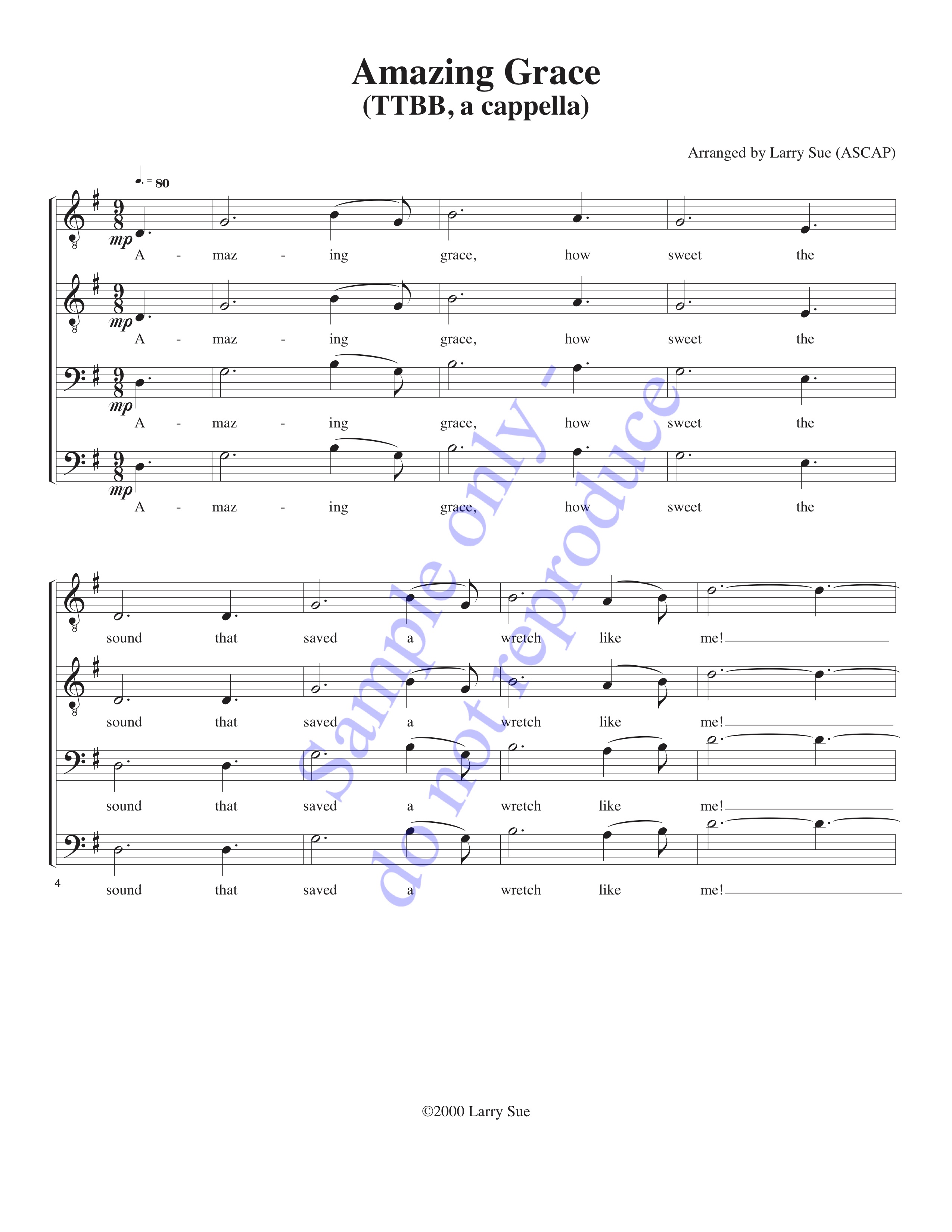

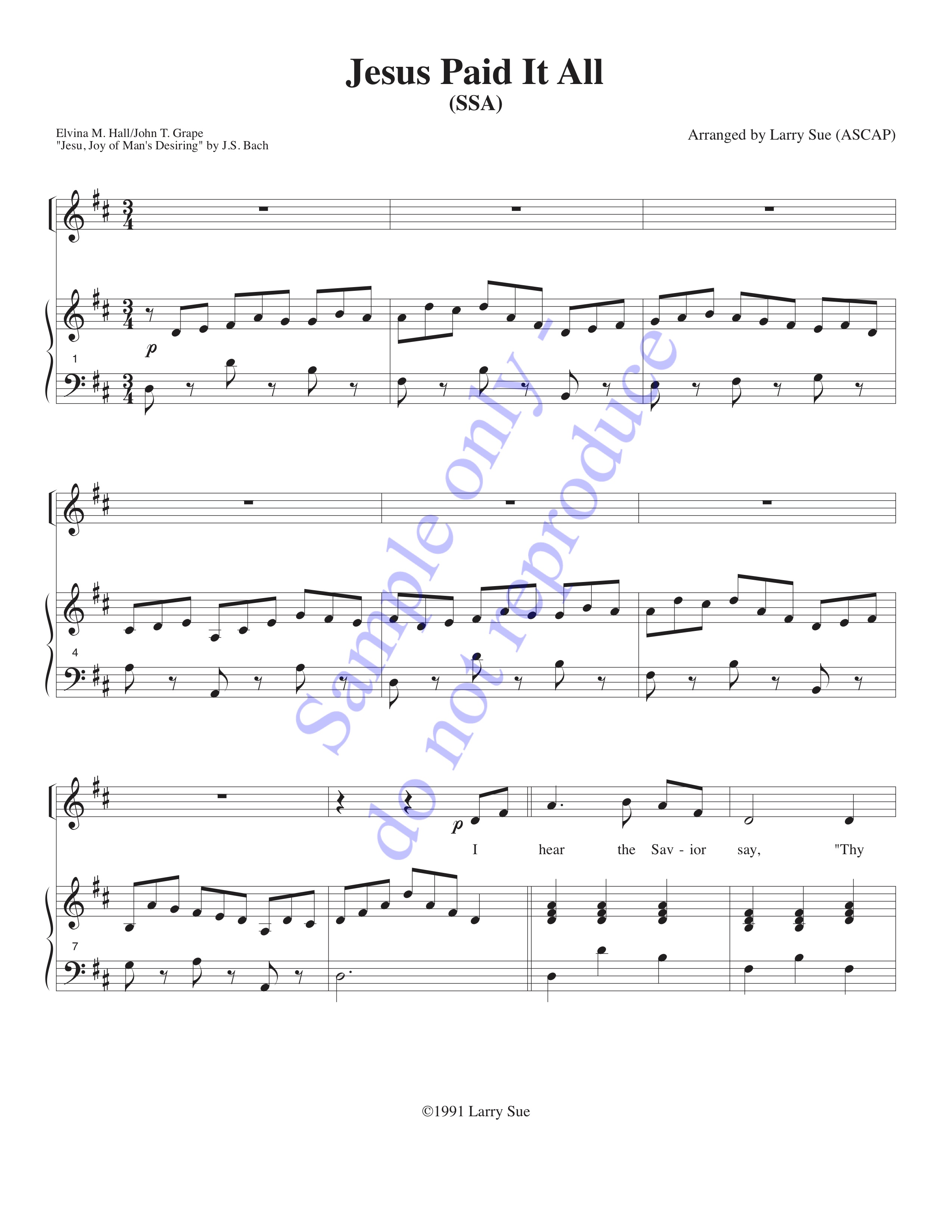

How I do it: I usually take sample music and, without piano, without tapes, without singing to myself, read the lyrics. Only then do I start to consider the music by playing through the accompaniment on the piano, checking for musicality and message integration. Only then will I consider any purchases. I find it unfortunate that, as of this writing, the “lyric review” stage eliminates about 90% of the music I receive, and the “musicality check” cuts the remainder by another 80% – so I find that I have an interest in only about two percent of the music I review (which is part of why I started my own music company, but that’s another story).

We must present our message clearly. This goes hand-in-hand with and augments technical excellence. We can be the best singers on the planet, but if we don’t present our message so that our congregations can understand it, worship by it, and be brought closer to God by it, we’re not doing our job.

We must live our message. You, as well as I, know how prone human nature is to brand a hypocrite. How much more when that person is in front where he or she is supposed to be setting an example! This doesn’t mean that you should require that your choir members attain a state of absolute sinlessness before joining (or else everyone, including the director, will have to leave), but it does mean that each person in the ministry should be setting an example of Christian living in their life.

We must be our message. I’ve prayed this lots and lots of times over the years I’ve been a choir director. Ultimately, it’s not the music, nor the words, nor the instruments, nor the voices which communicate the message, it’s us, and therefore we must be submitting ourselves to God’s leading us so that He can work through us.

Guiding Principle VI: Plan your rehearsals.

This, of course, follows hard on the heels of the bit about “getting out of survival mode.” It’s essential to plan your rehearsals – the work you put into being ready for choir practice will reflect itself in the way your choir practices! If you’ve never done this before, I recommend you develop the habit because it’ll make your life much more bearable and coherent, and your choir will appreciate your diligence.

Here are some ideas to prepare for rehearsals:

Plan your next rehearsal immediately!

I like to plan what I’ll be doing at the next rehearsal the day after the previous one. That way, I still have a pretty clear picture of what we need to do next time and can put it on paper. Bear in mind that next week’s work is based on this week’s work, so having the details fresh in my mind is essential.

Put your rehearsal plan in writing.

For Living Water, I usually word-process and print my rehearsal schedules (you have to decide if you want to do this), but regardless, I do write them out. It doesn’t have to be anything elaborate, but it should detail what you plan to do so that you’ll have a plan to follow. I also allocate time segments so that I know whether I’m on track during the rehearsal because if I don’t control the time, I won’t usually get everything finished.

Start with easy stuff, put the hard work in the middle of the rehearsal, and then unwind.

Everyone needs to warm up. For some people, this is a physical thing; their voices just need to get into singing mode. For others, it’s a mental thing; they need to put a long, frustrating day of work behind them. So I usually start with easier pieces. By the way, I don’t usually sing vocalises at the beginning of rehearsal any more… I’ve found that a judicious selection of working topics for those initial easier pieces is equally effective, and actually accomplishes something toward preparing us to minister.

Once everyone’s warmed up – and before people start to get tired – I attend to the really serious work. Bear in mind, though, that I don’t usually spend more than an average of about fifteen minutes per song unless we have an extremely tough repertoire for the rehearsal! But it’s time to work, and I’m blessed with a choir who likes to work because they know how it all comes together in their ministry.

After the “hard work” part, the rehearsal usually unwinds with some more of the easier pieces, or with song which we know fairly well. And then we pray and go home.

Use stylistic variety to advantage.

Provide a good mix of musical styles and feels through the rehearsal. concerts, CDs and tapes don’t present musical selections of only one style (in fact, they vary quite a bit most of the time), and neither should you. Some directors take this so far as to make their rehearsals more of a worship service (with lots of work happening…).

Teach sight reading.

If you have a choir which sight reads effectively, you’ll save at least 50% of the time required by a choir which doesn’t. It means that you can use that time to work on diction, timbre, blend, and a host of other things which the other choir may never, ever address because they’re still pounding parts on the piano.

The only way to learn to sight read is to do it (sounds like a Catch-22, huh?). You can lecture about it, but people won’t develop the skills until you give them the opportunity to try. For what it’s worth, I’ve also written a series on sight singing…

Most of the time the first song in Living Water’s rehearsal is a sight read (okay, I lied a little bit a few paragraphs ago). Sometimes it’s something which a few of the members know; other times it’s music which I’ve just written. This is a great thing for me because not only do we work on our sight reading, but I also get to introduce new music at minimal cost: if they don’t like it, they’ll never have to see it again (but then, I hope that you have a choir which is as eclectic in their musical appreciation as I do). I’ve been starting with a sight read for over six years now, and the benefits have been tremendous!

Maintain repertorial recall.

My, my, what fancy words… All that means is to provide a way to ensure that the choir has an opportunity to remember what they’ve sung in the past – by singing it. That way, you’ll also have past repertoire on tap when you need it (maybe your pastor will ask you to sing a concert on three-week notice some day…).

I implement this via “The Last Request.” Each week, one of the members (selected by rotation through the roster) gets to choose anything – literally anything – from our choral library as the last song of our rehearsal. We’ve had quiet, meditative anthems, selections from Handel’s Messiah, and just about everything in between – and I find it exciting because I then know which of our songs have had the greatest effect on our members’ lives.

Love your singers.

Remember, remember always, that love is the essence of Christian ministry. Without love, nothing we do makes any difference in the Church or in the world. And in the same way it’s true outside the choir room, it’s true inside the choir room.

You can remember their birthdays. You can send cards or make phone calls, but perhaps the most effective thing you can do is to sing “Happy Birthday” to that special person during rehearsal. And yes, you can give presents (which I do), but remember that once you give the first one you’re on the hook for life.

Just to fill out the topic,

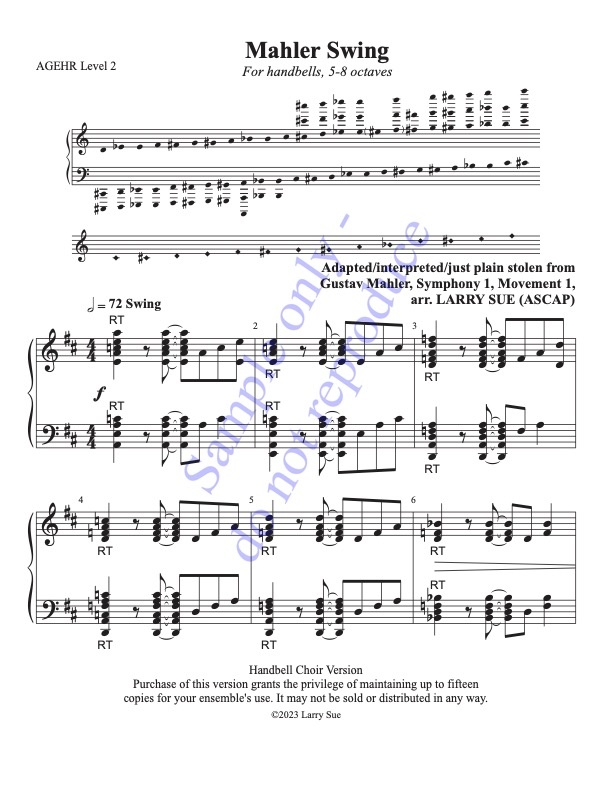

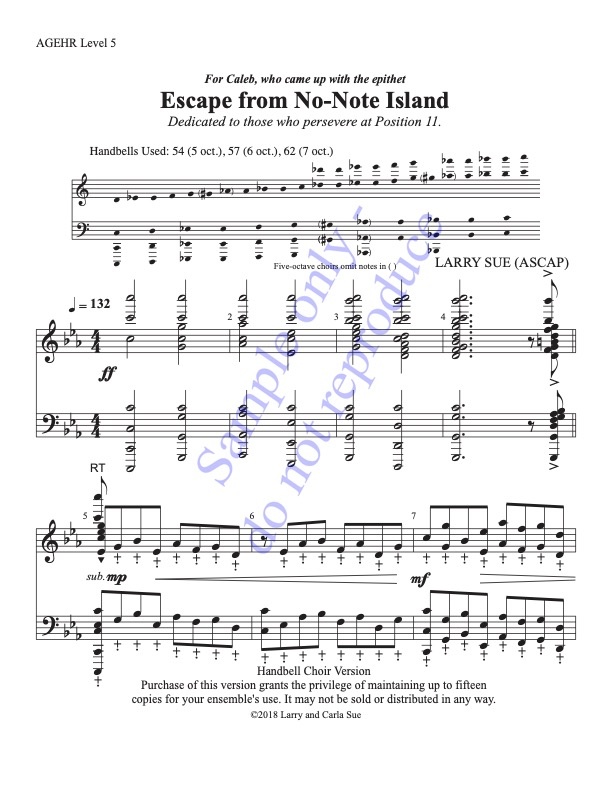

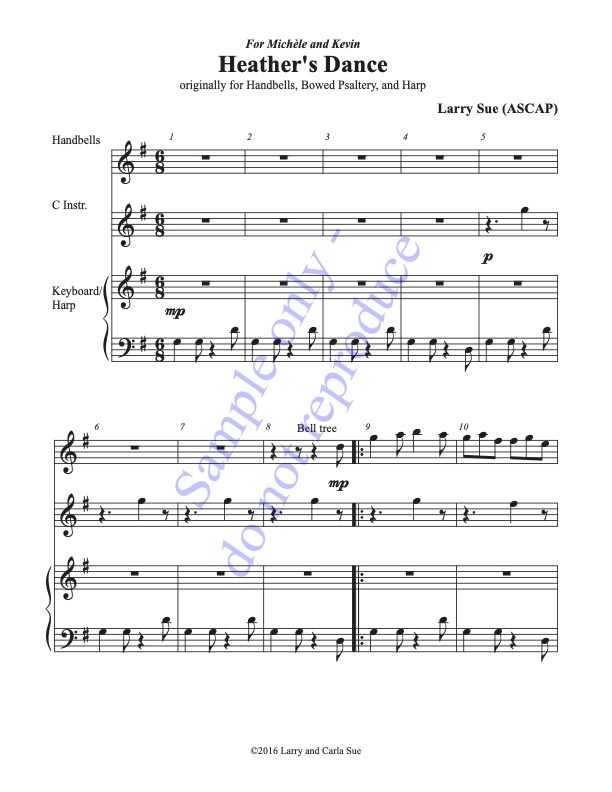

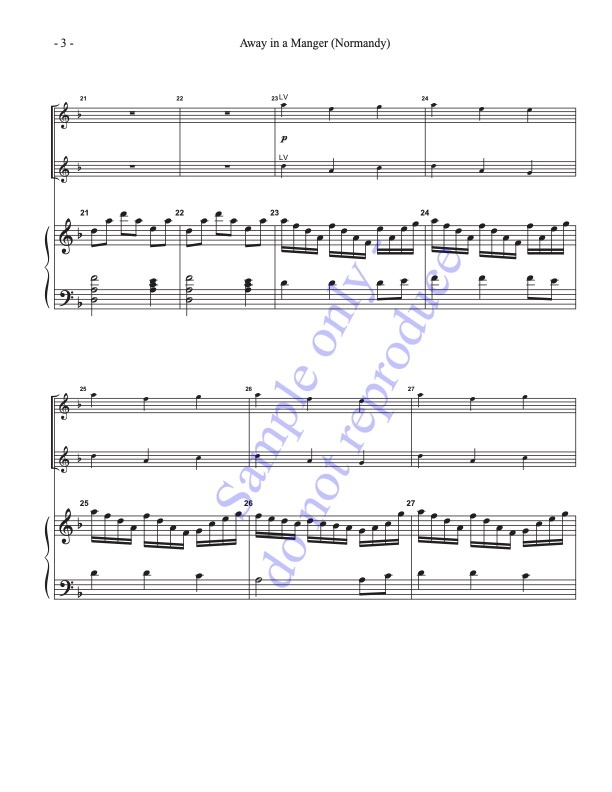

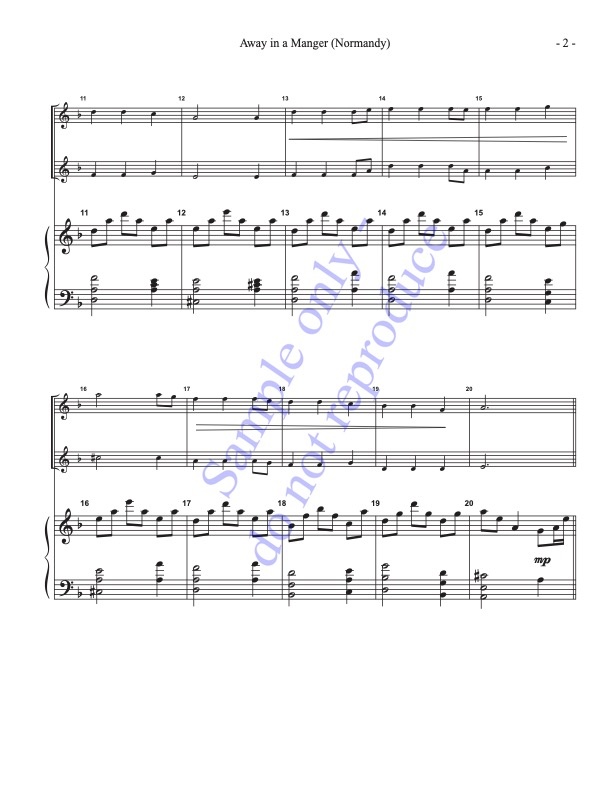

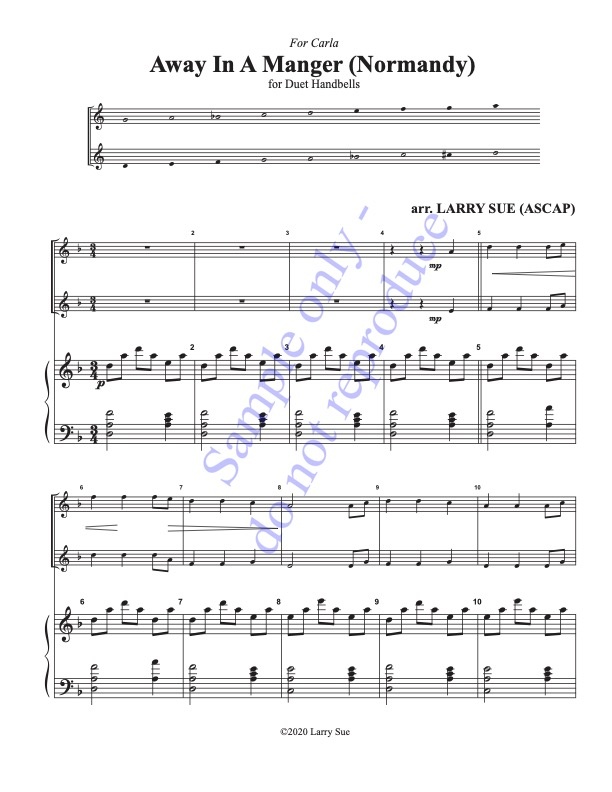

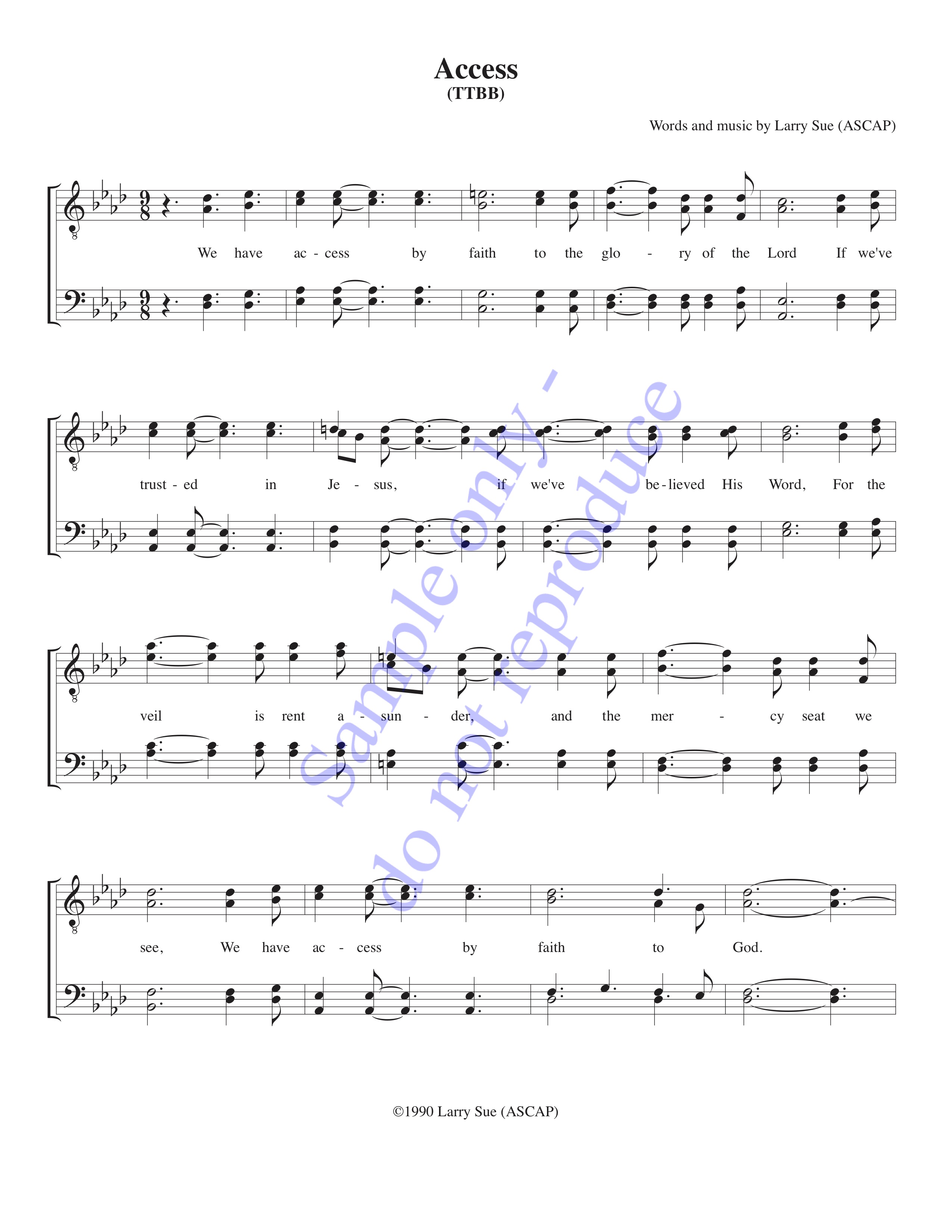

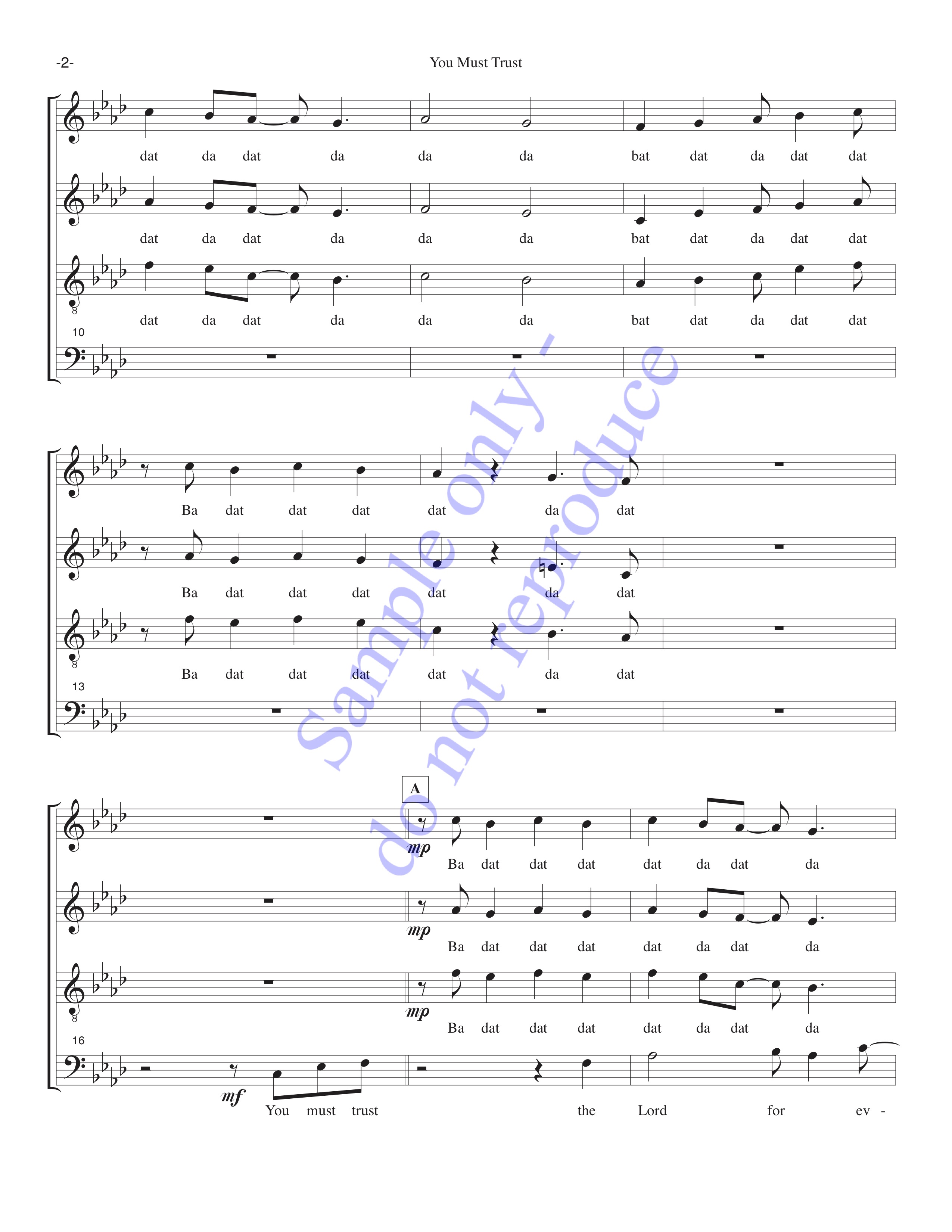

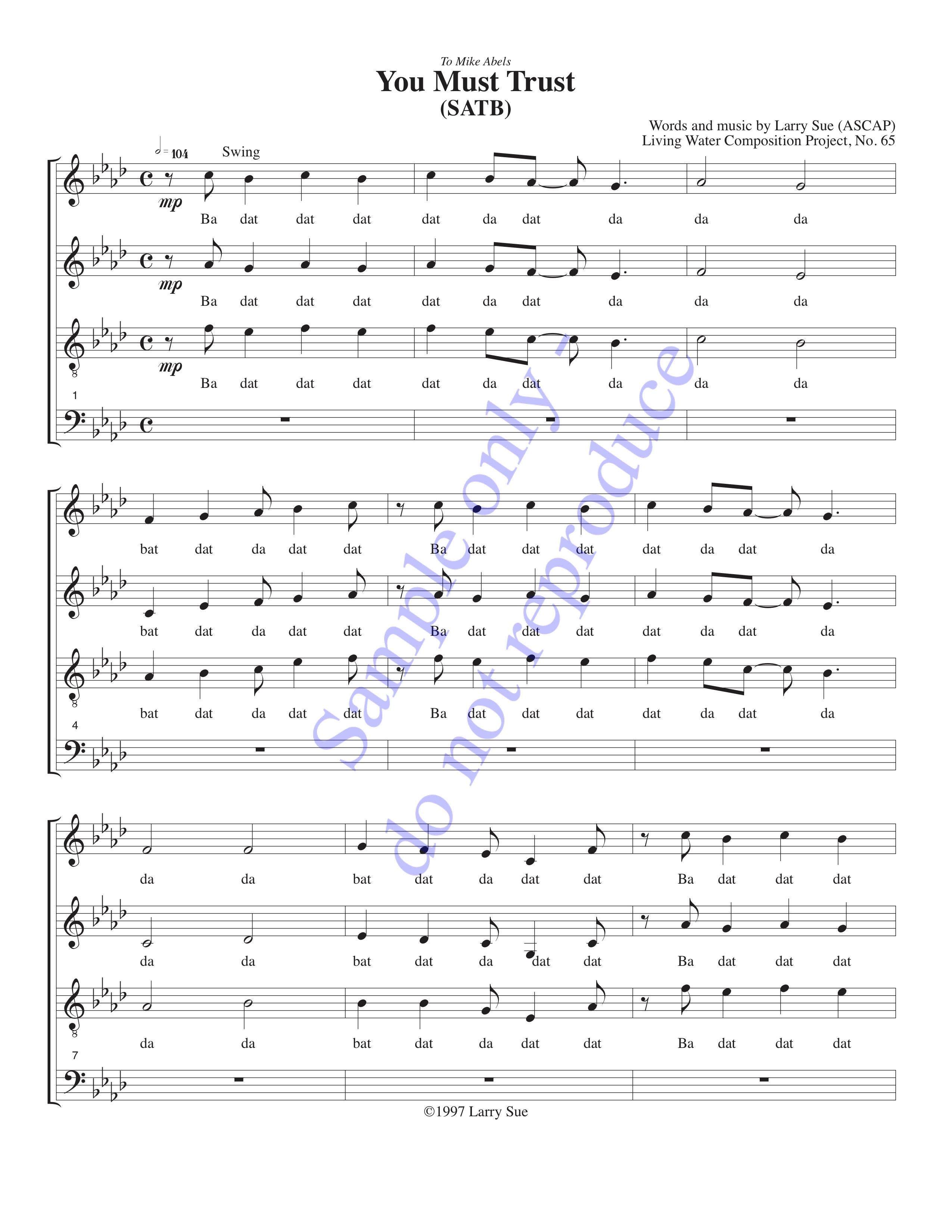

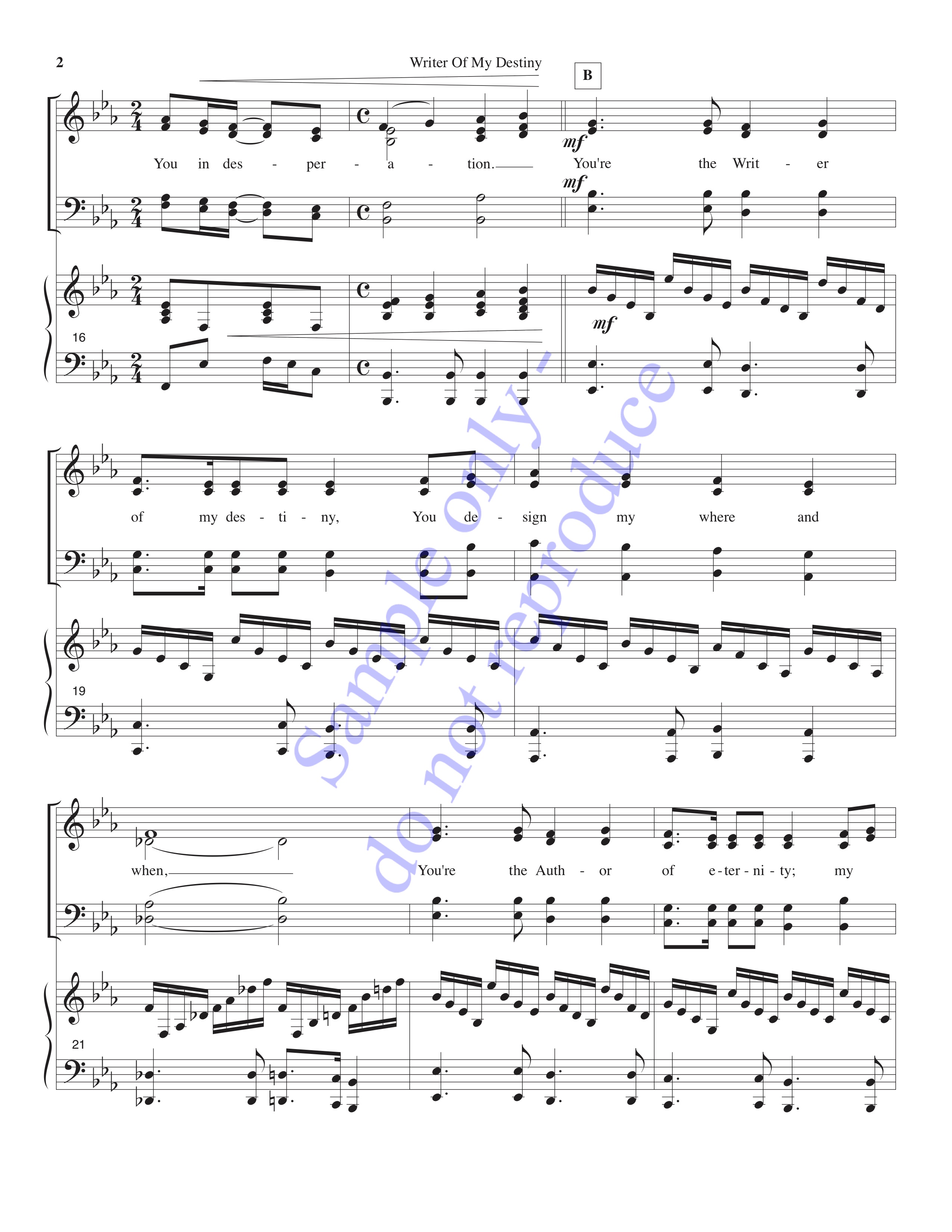

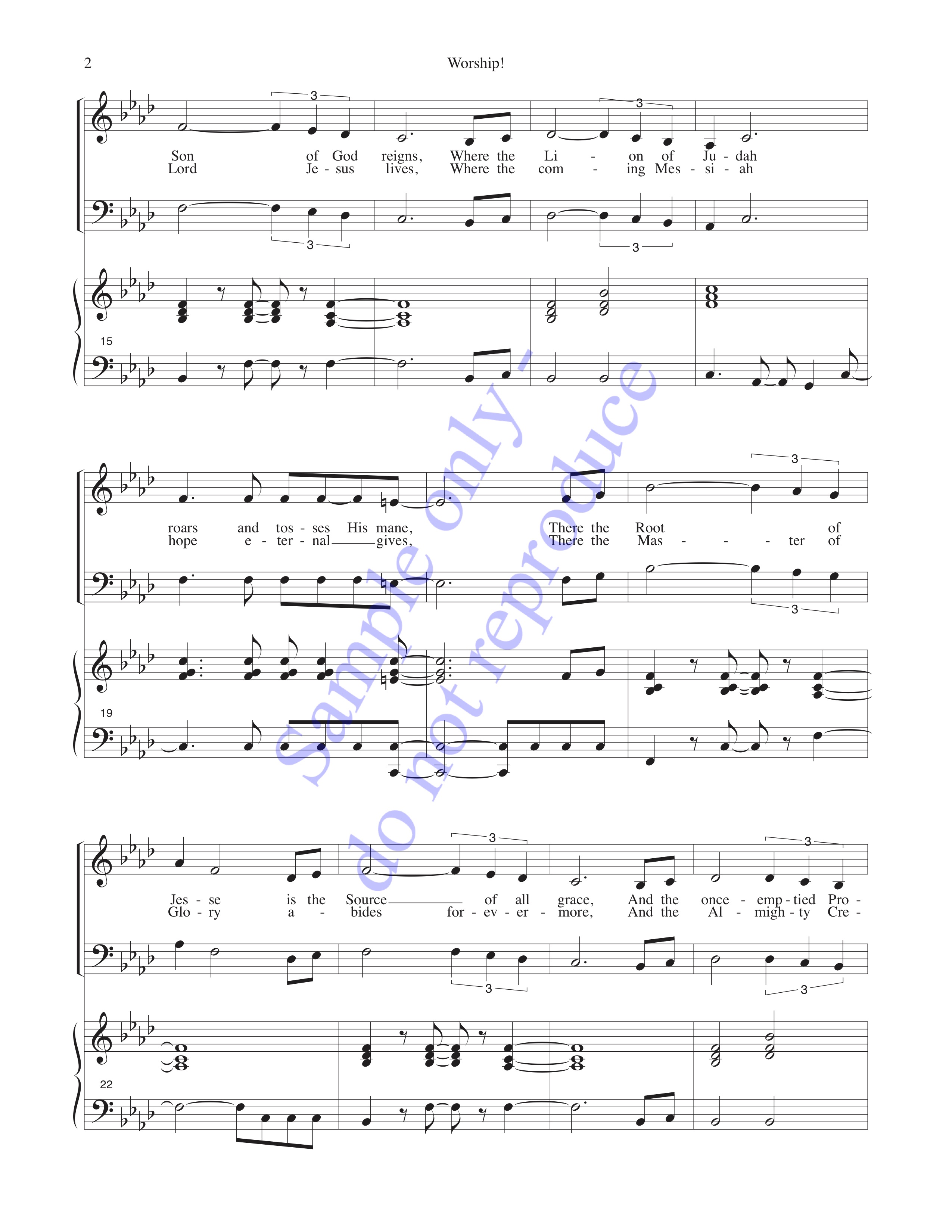

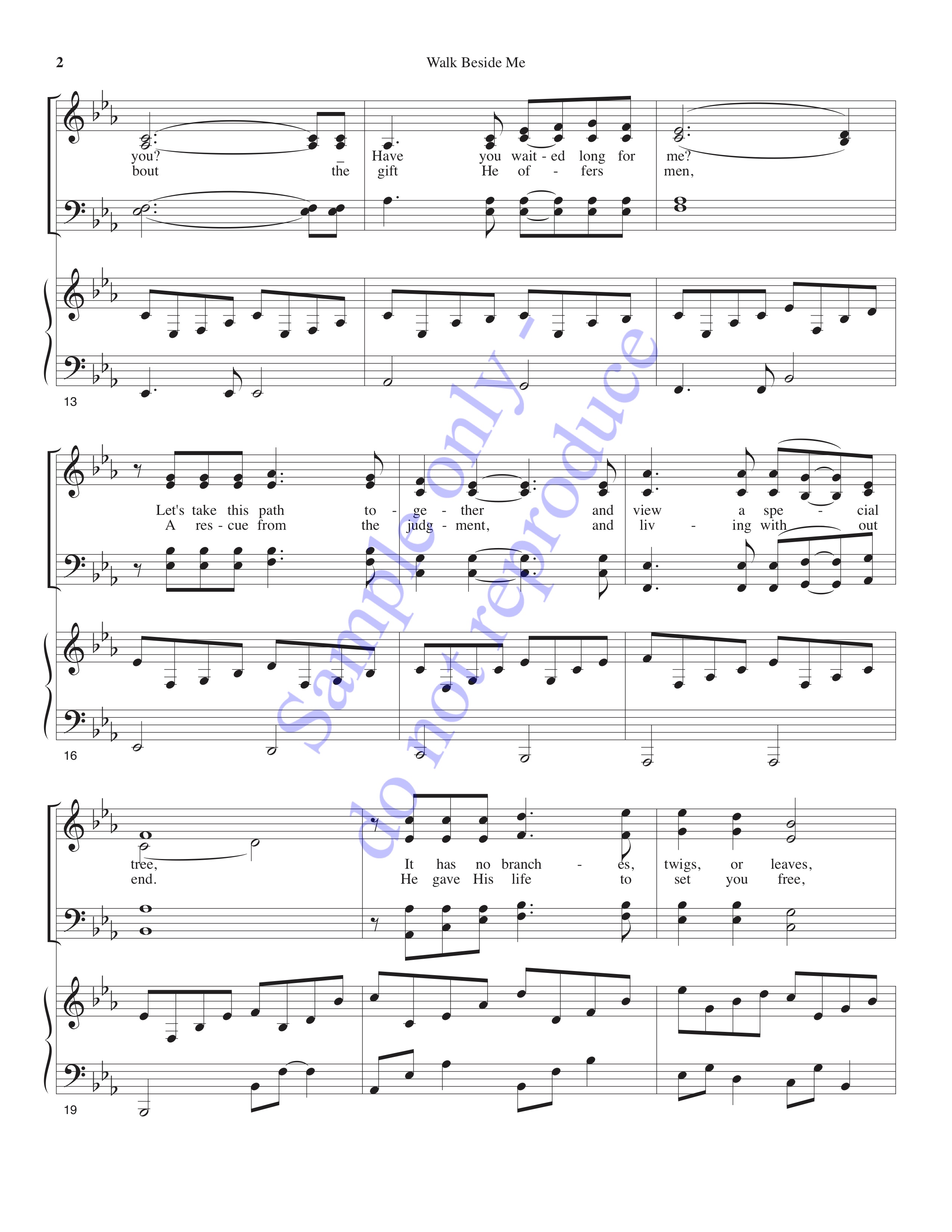

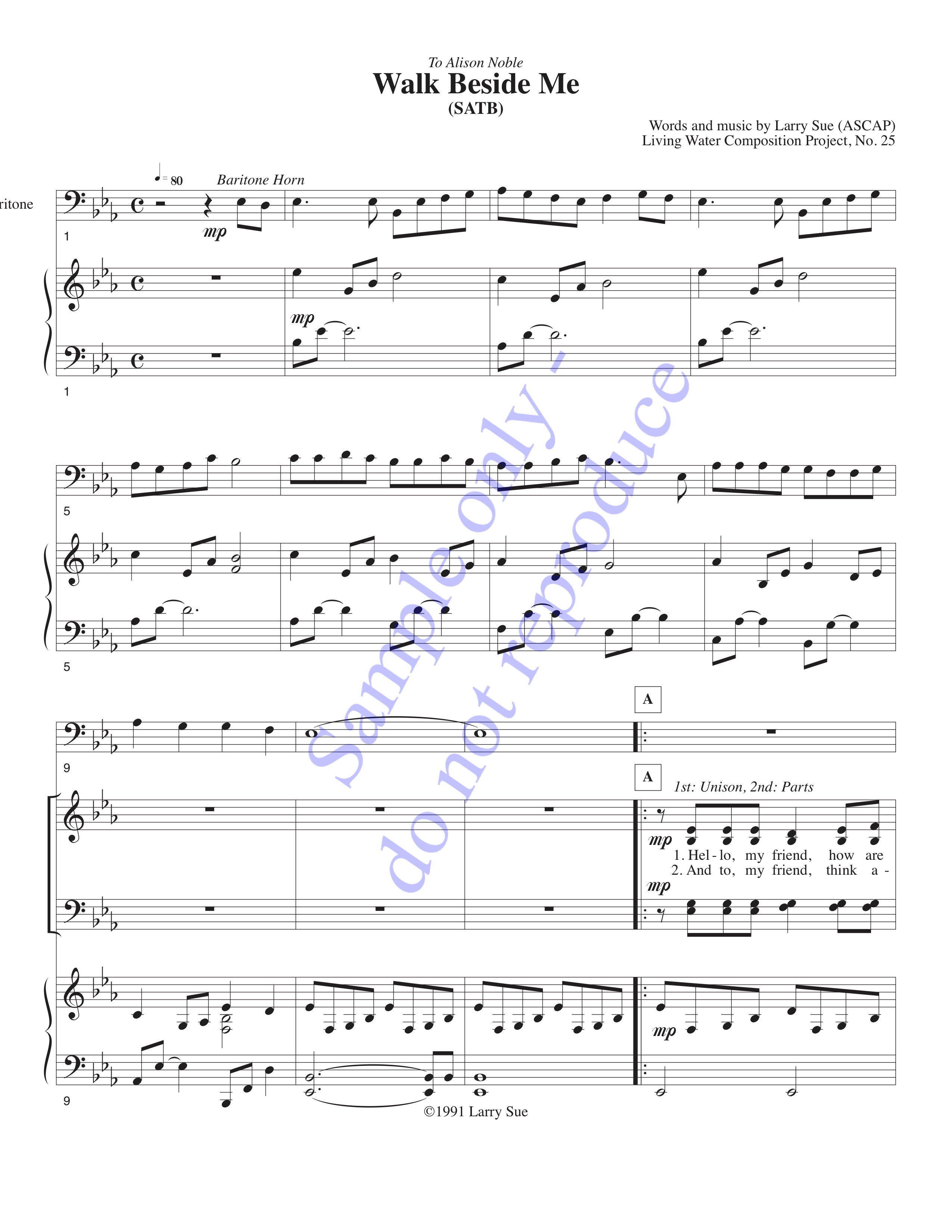

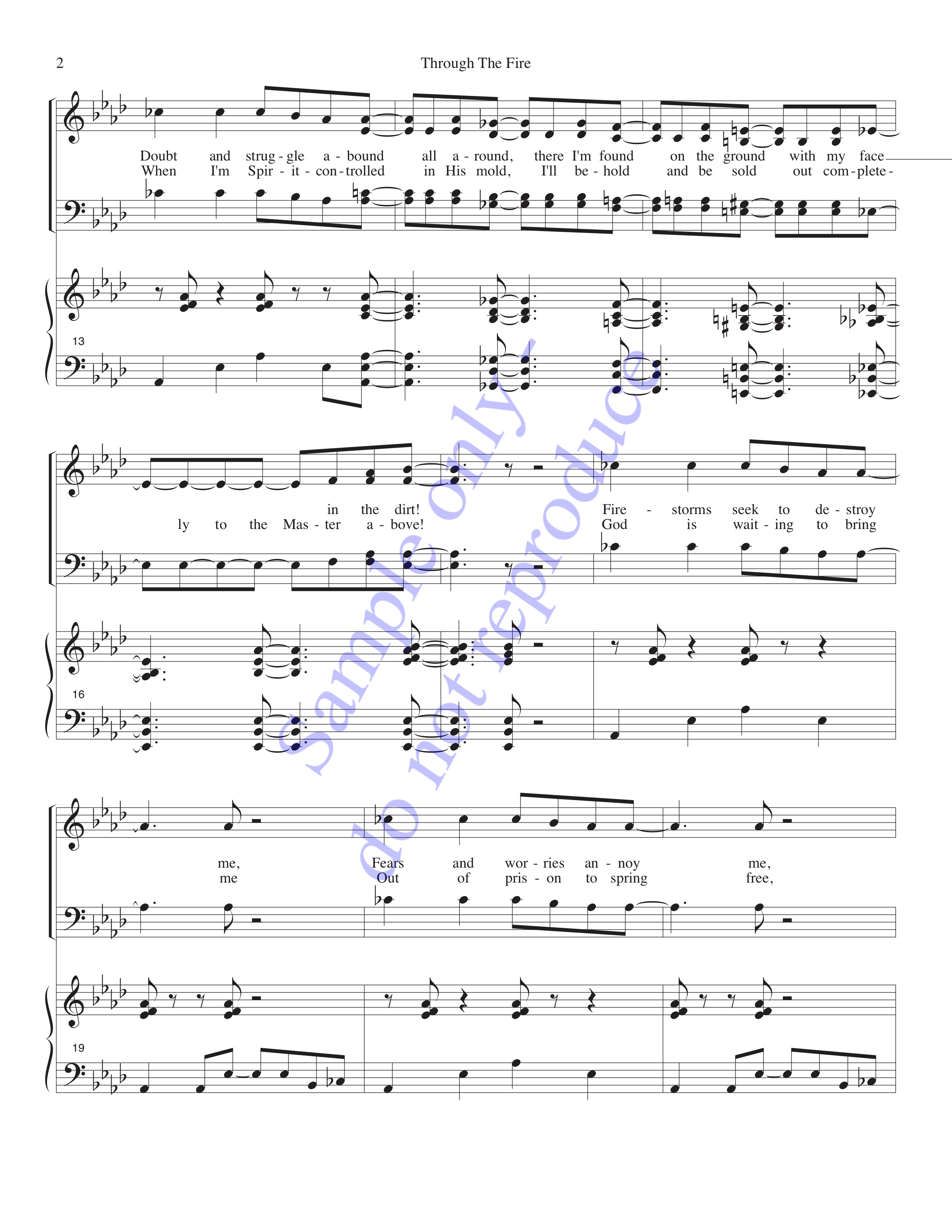

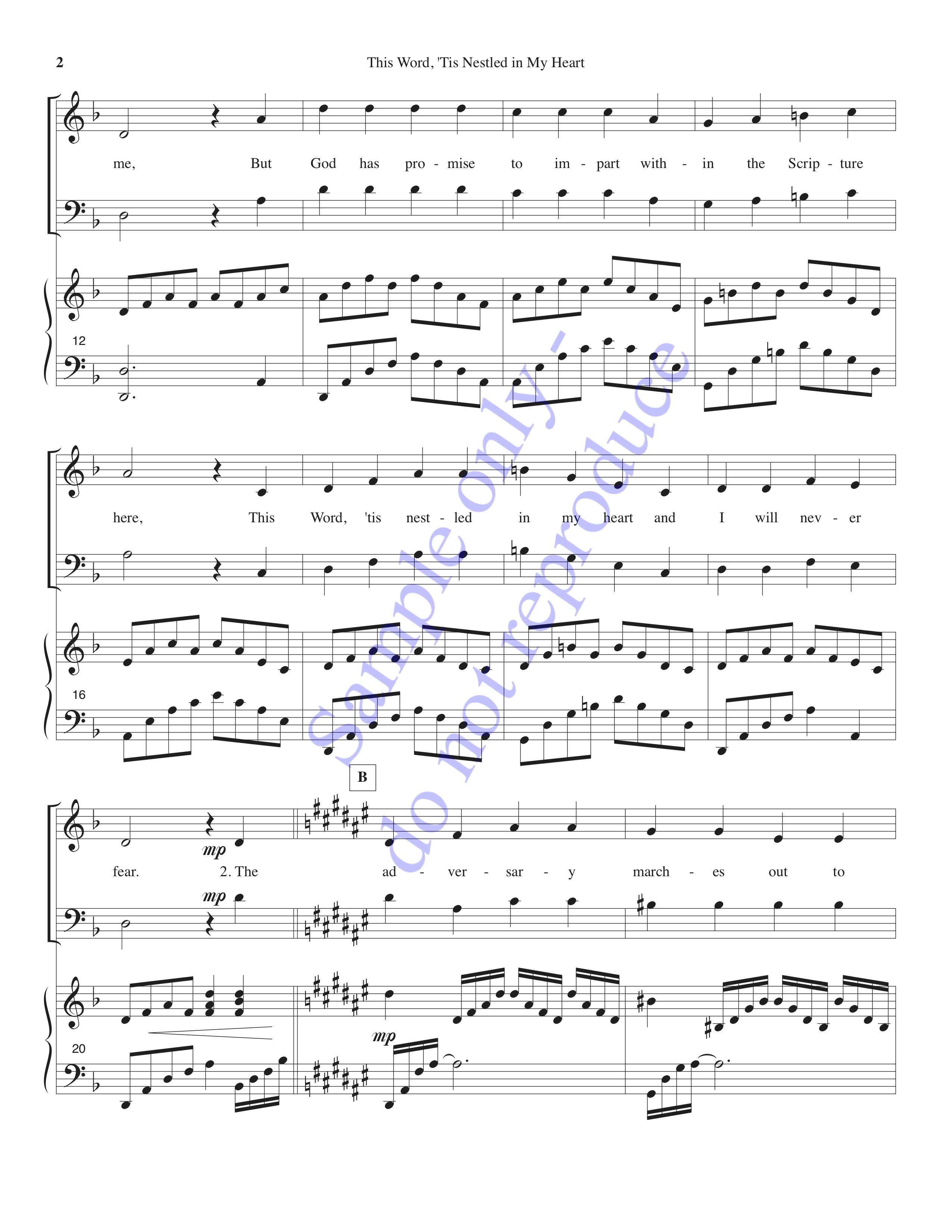

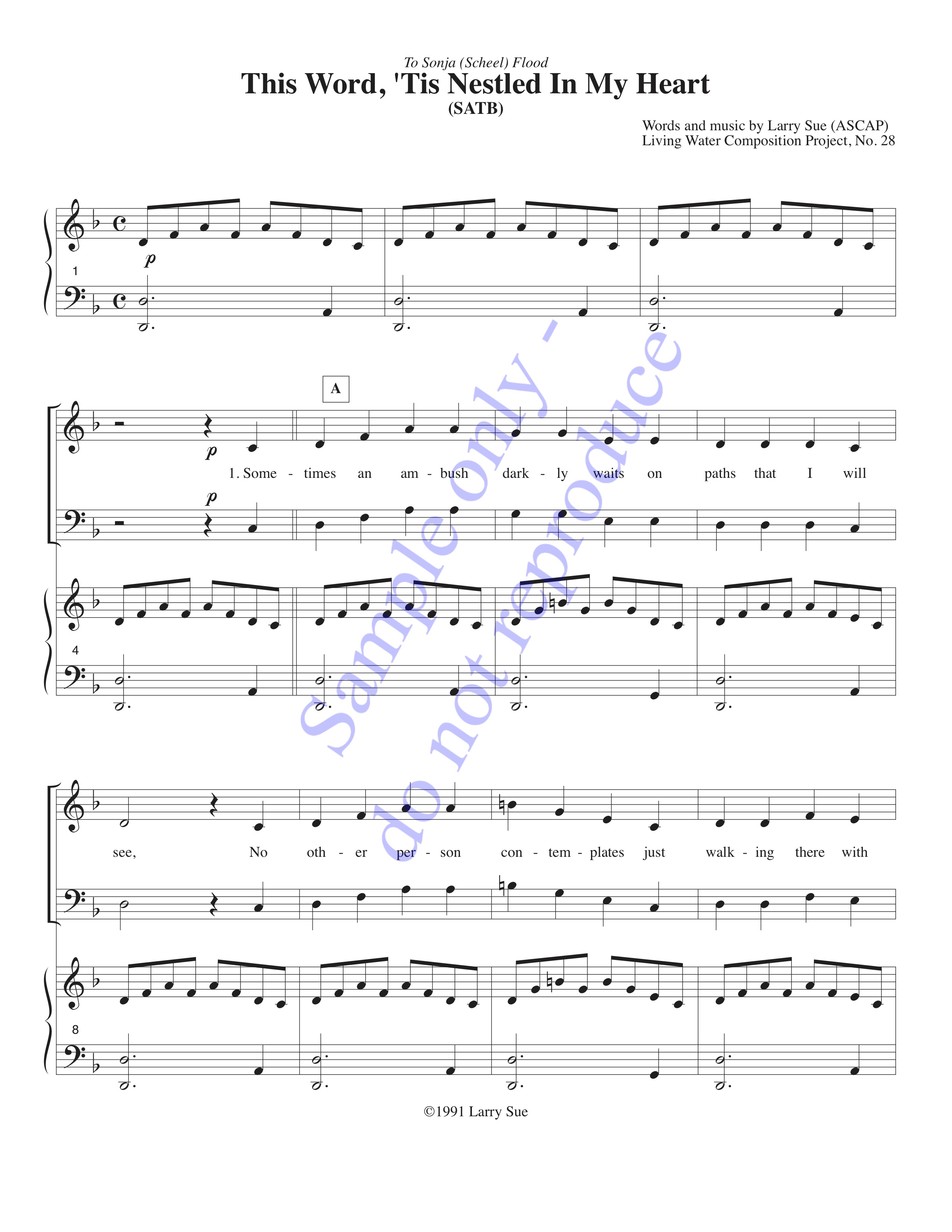

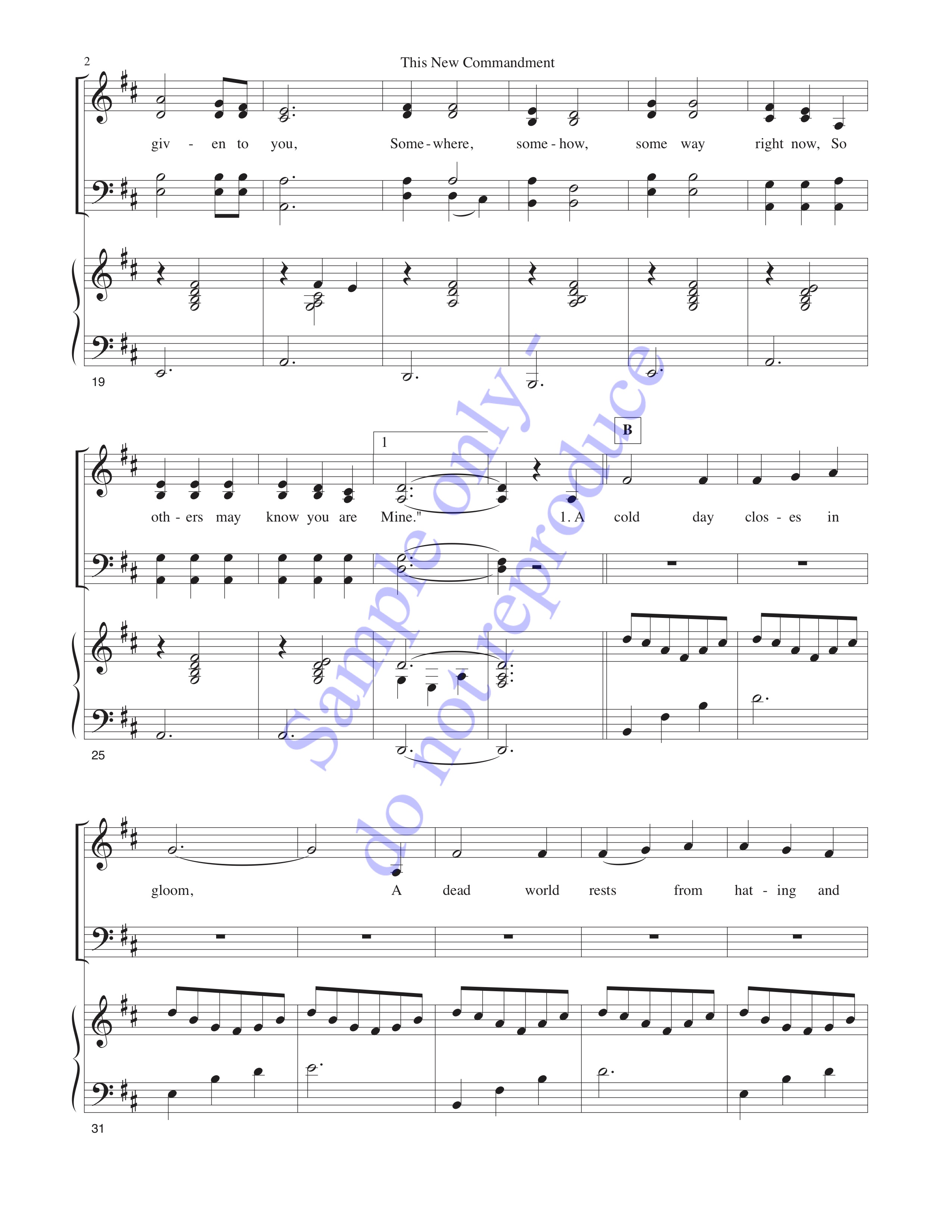

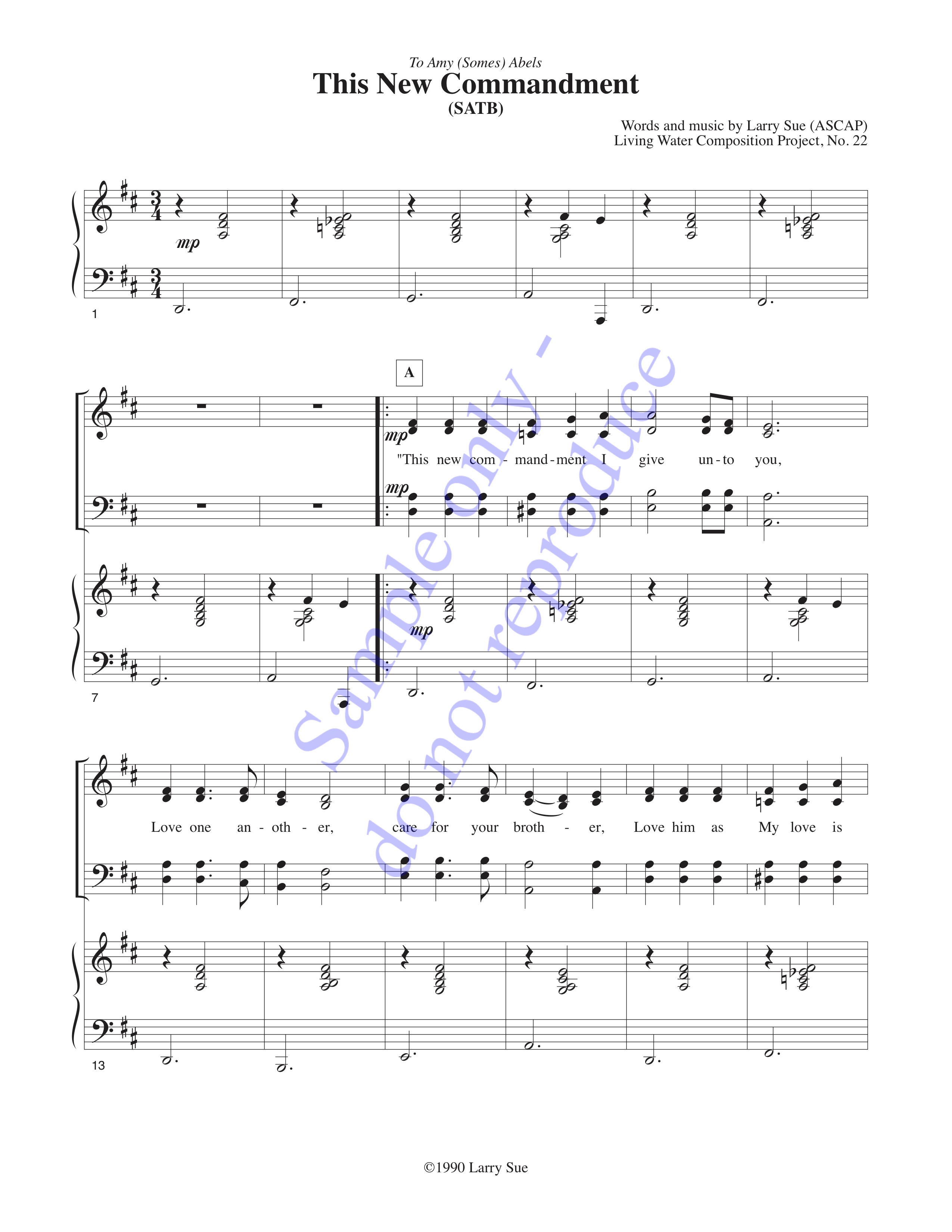

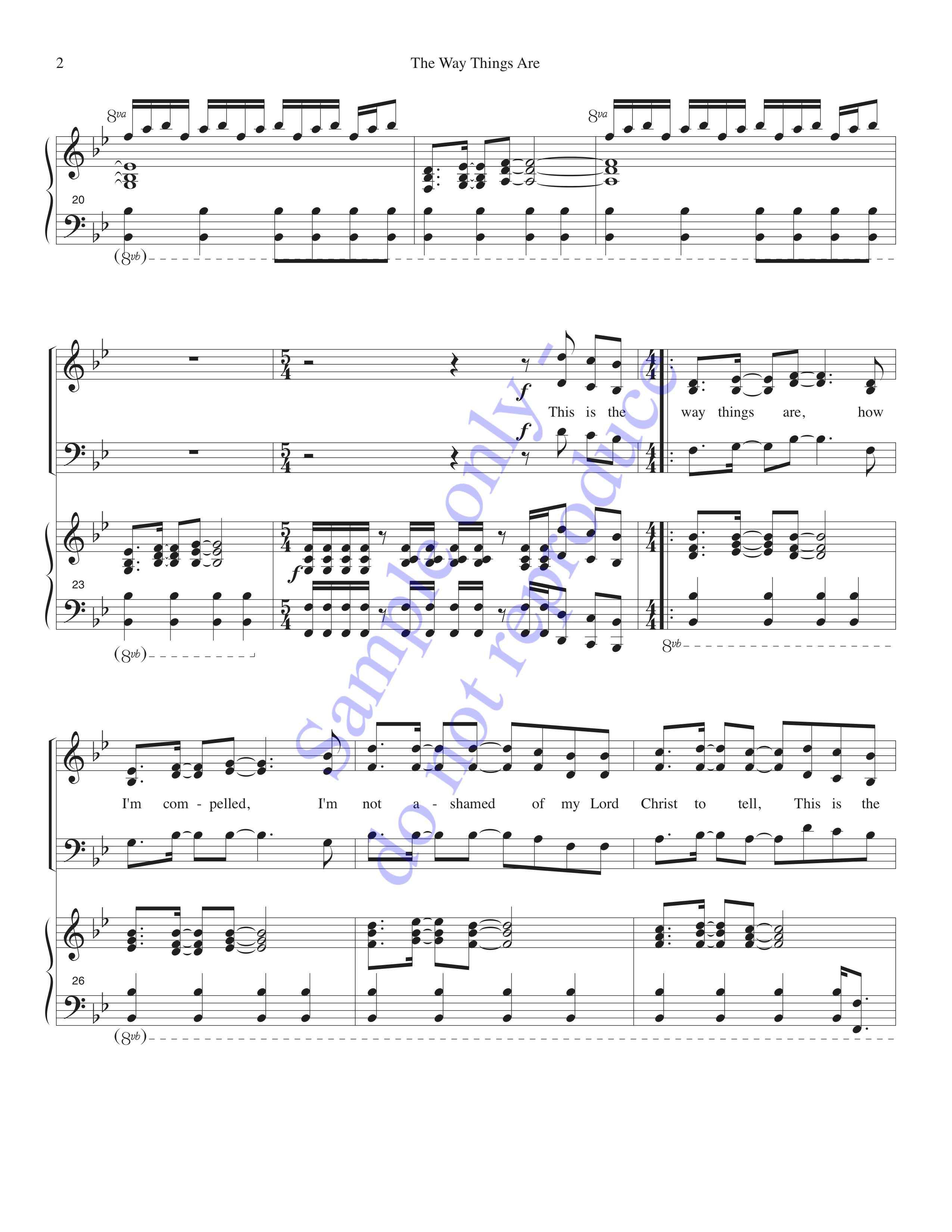

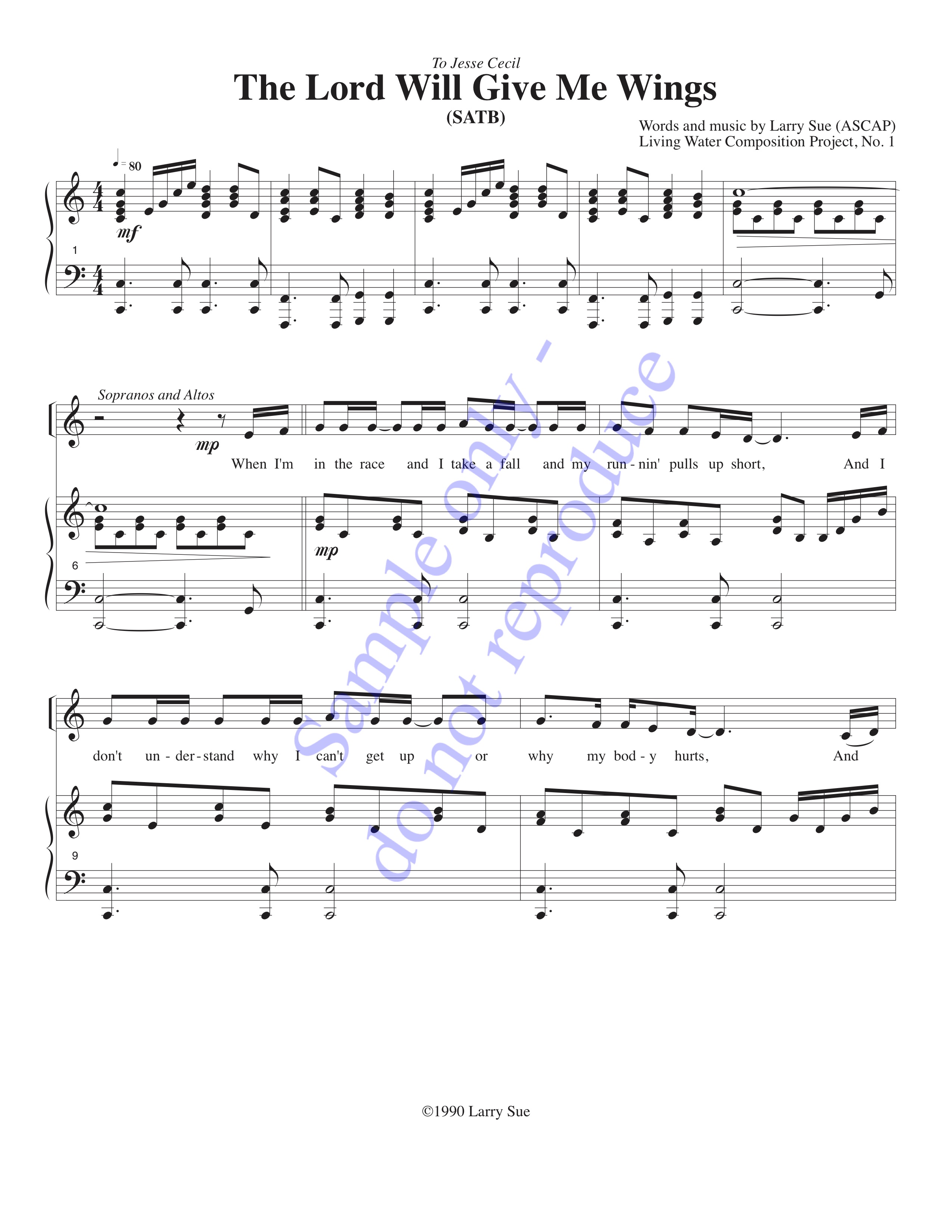

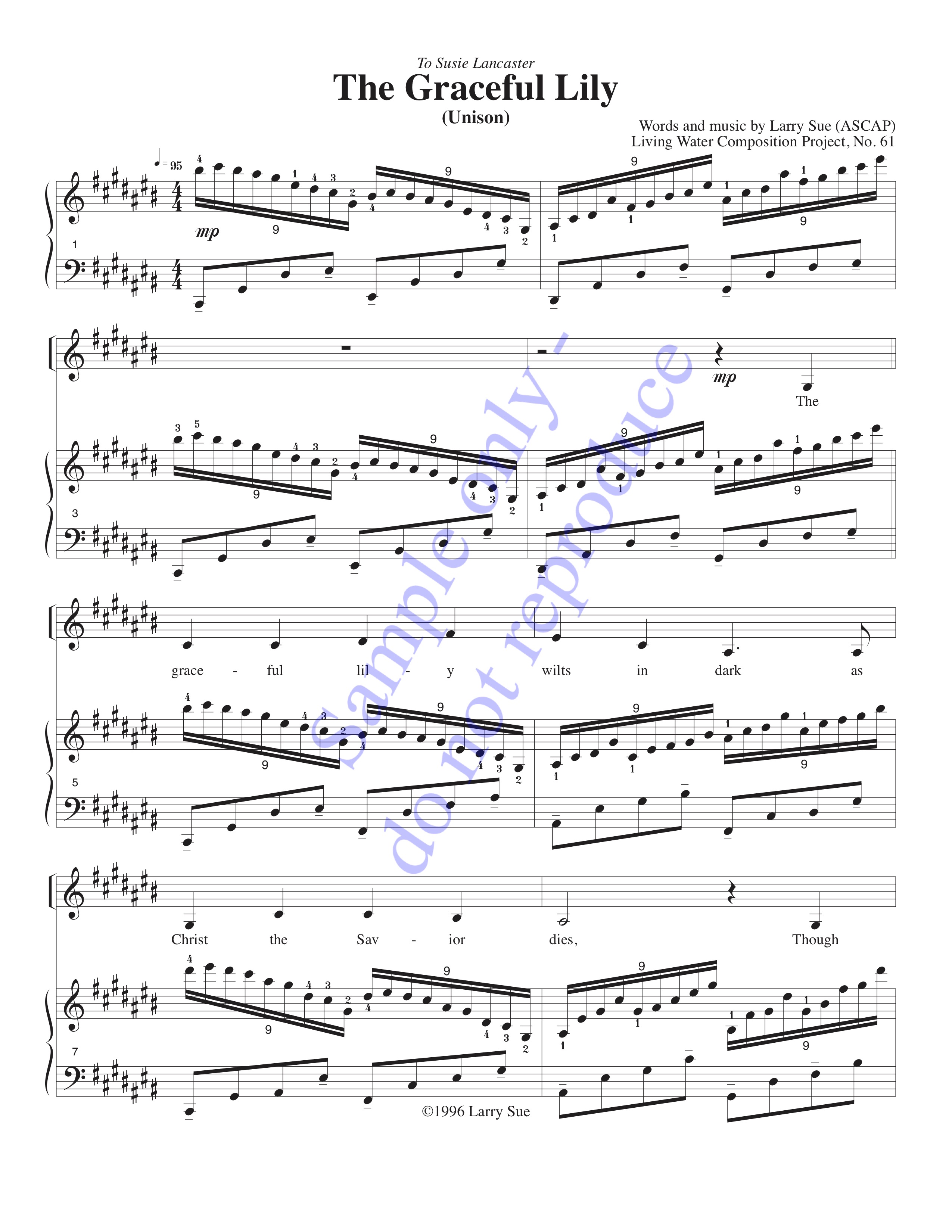

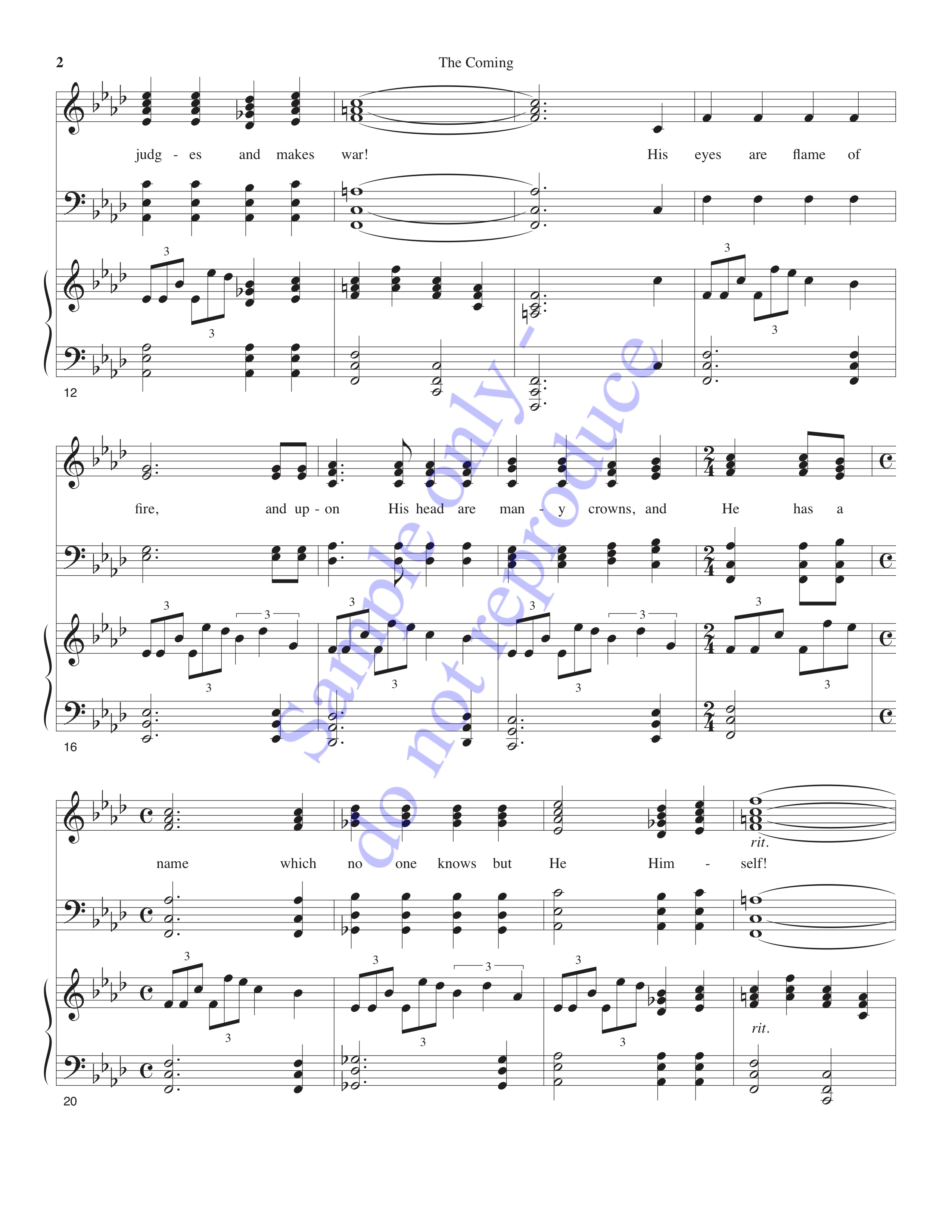

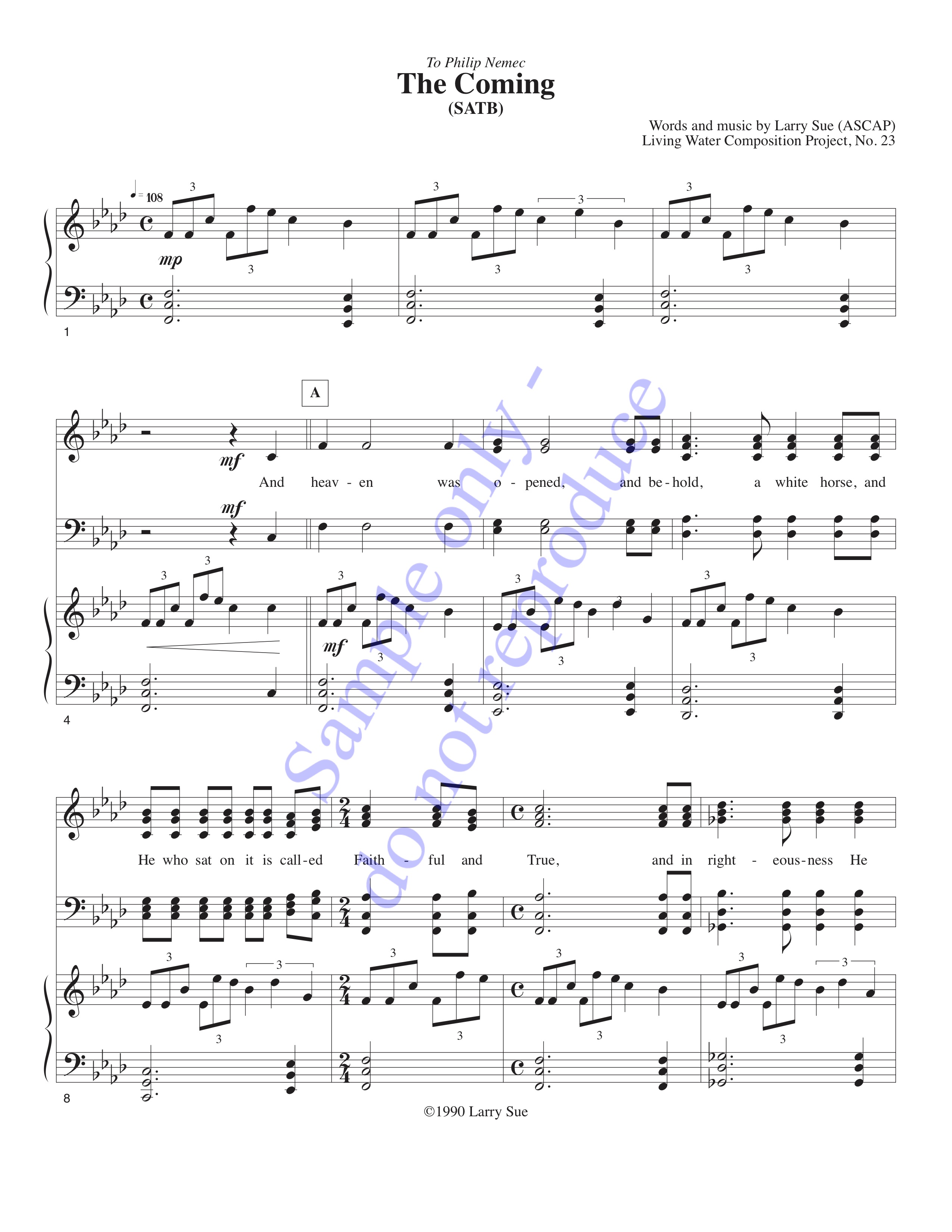

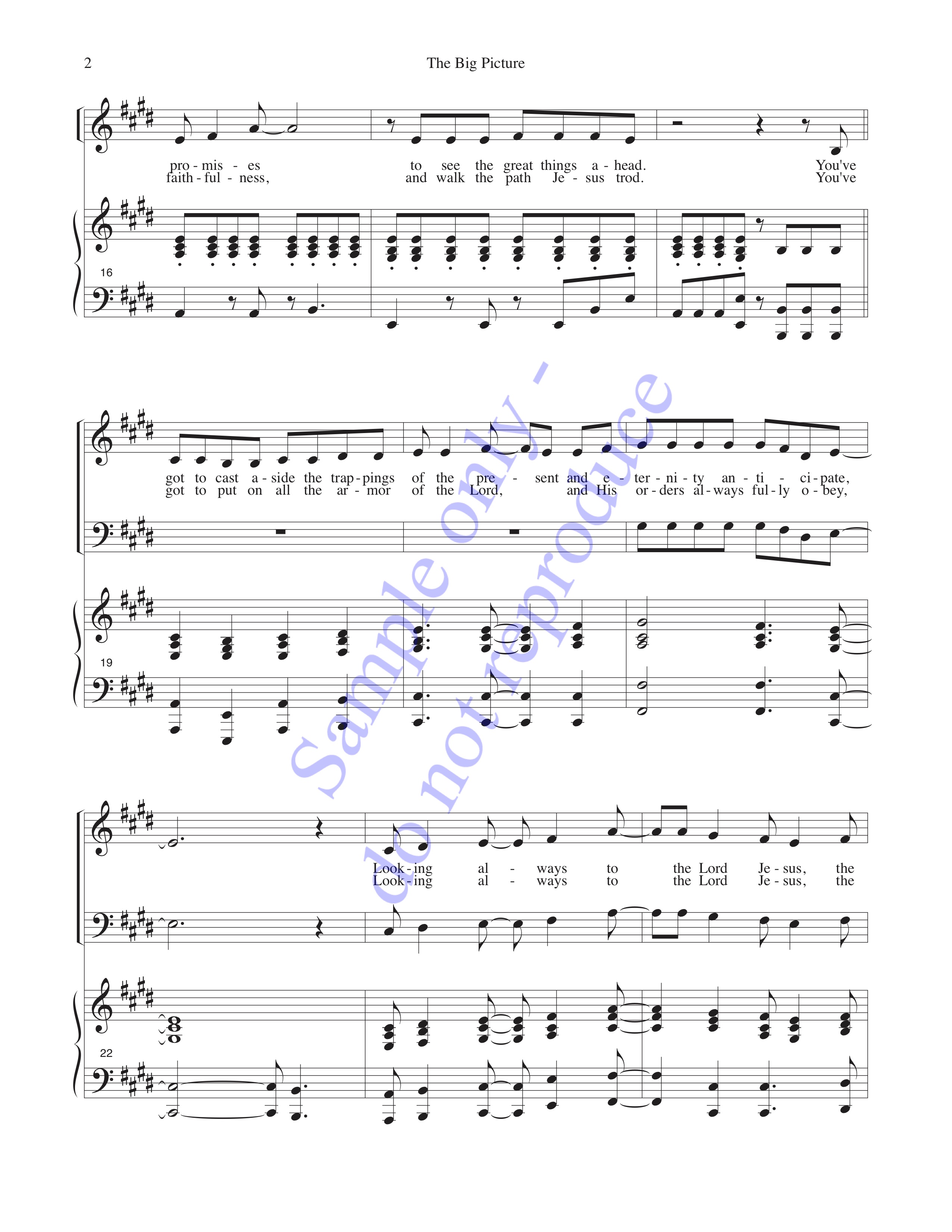

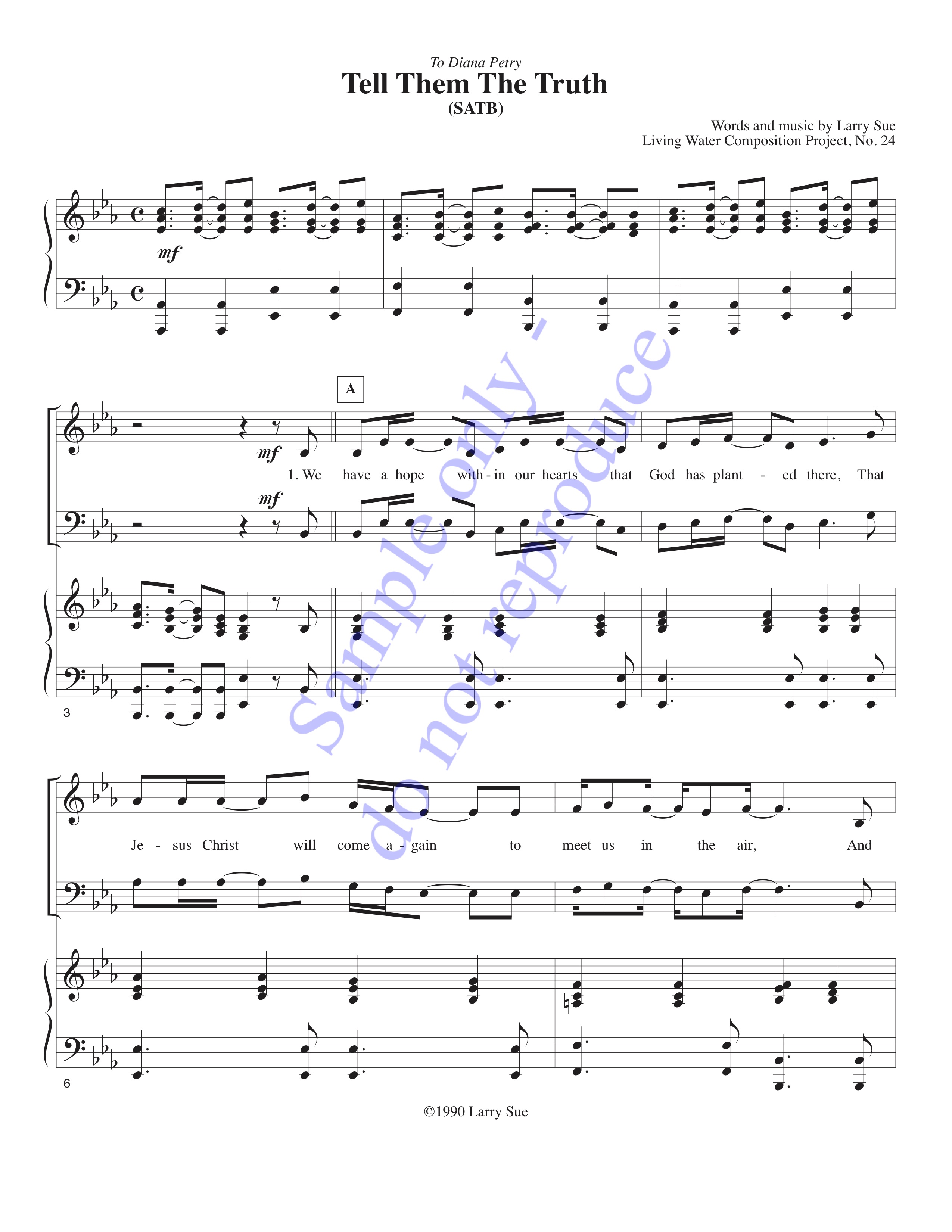

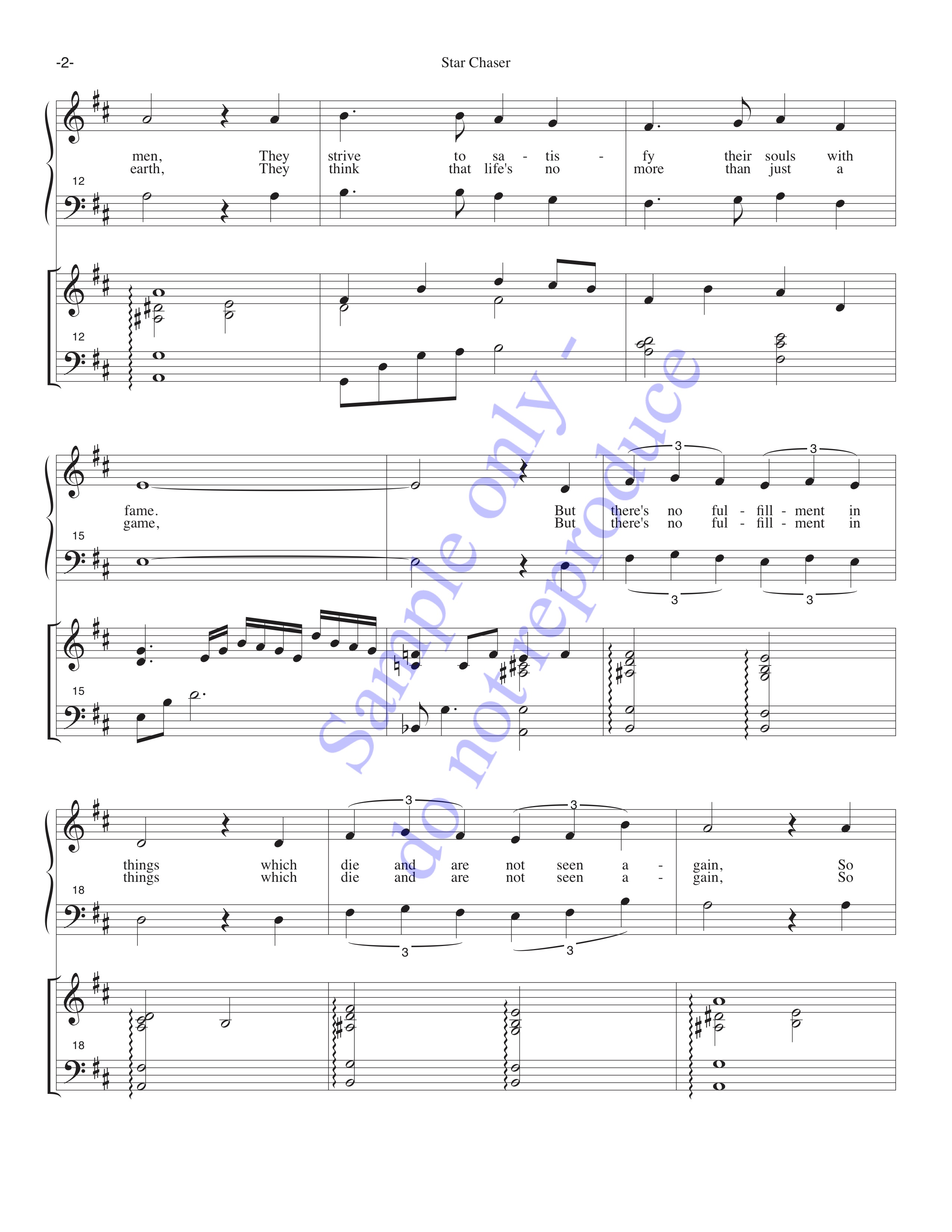

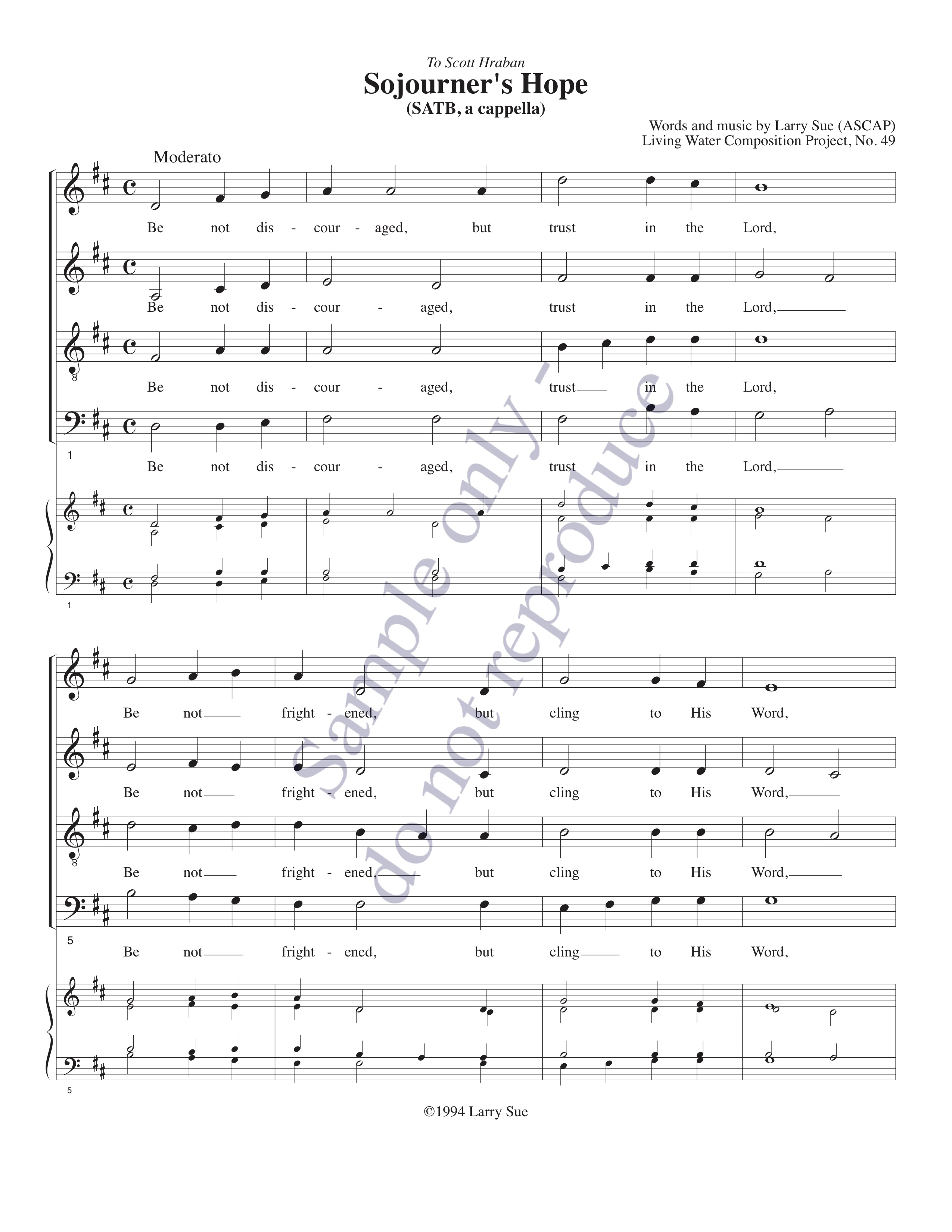

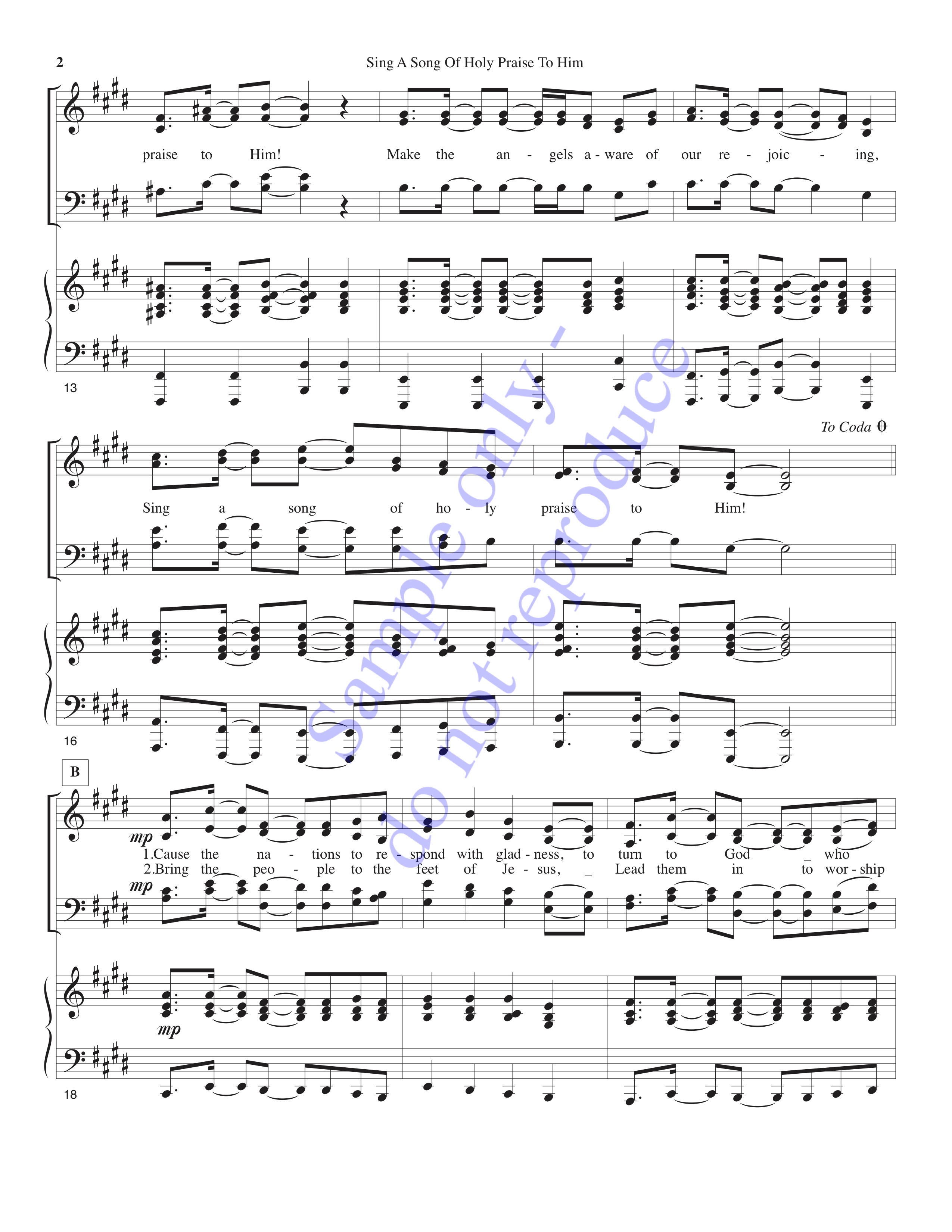

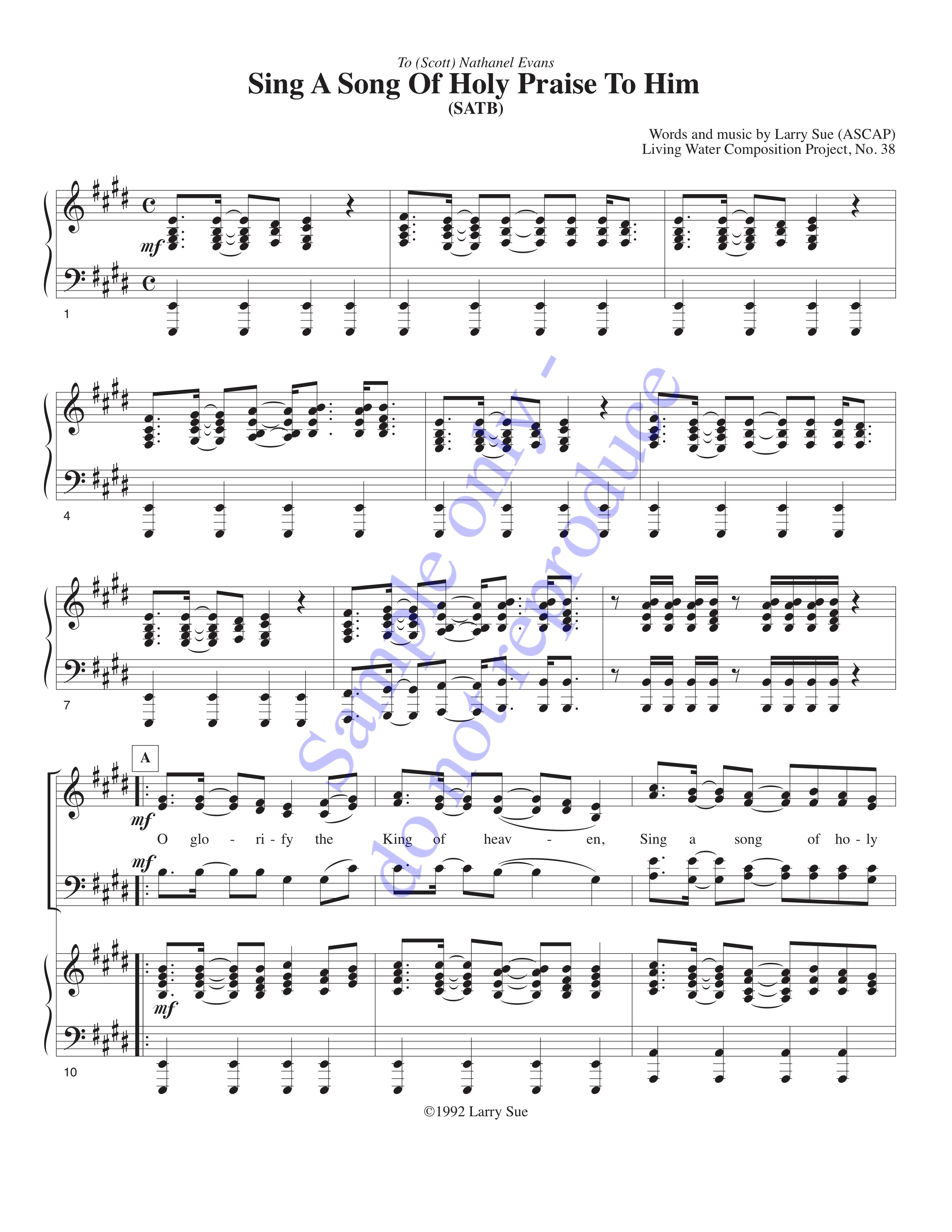

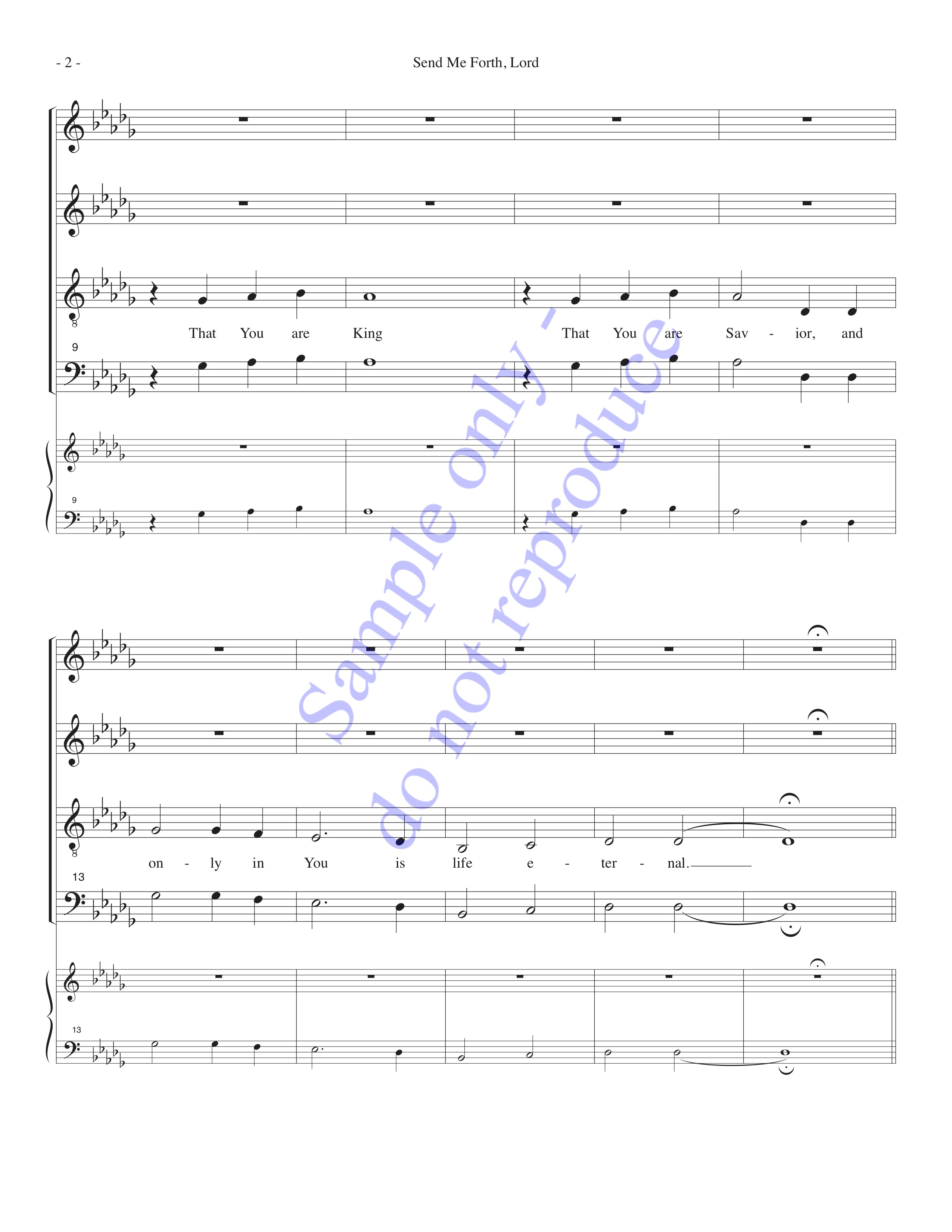

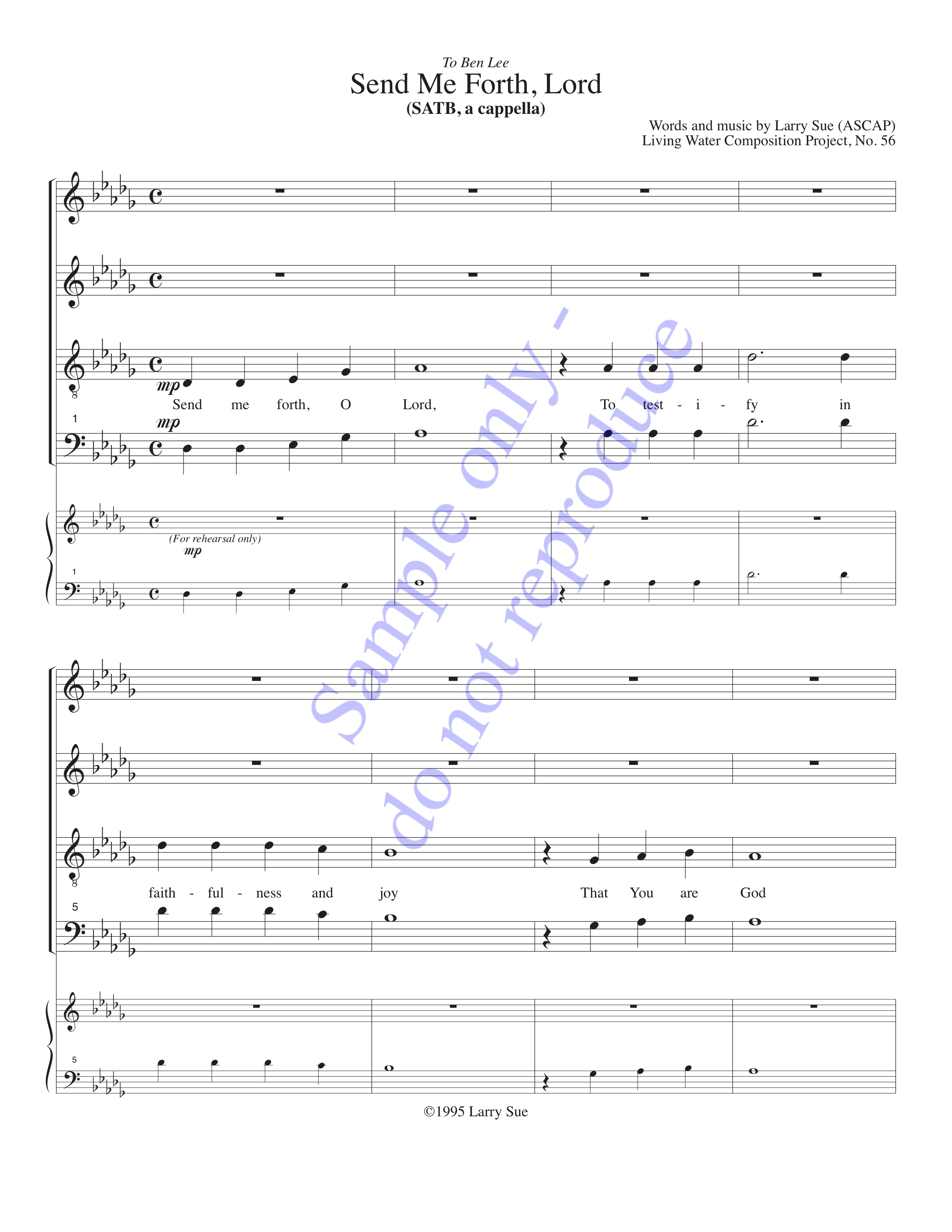

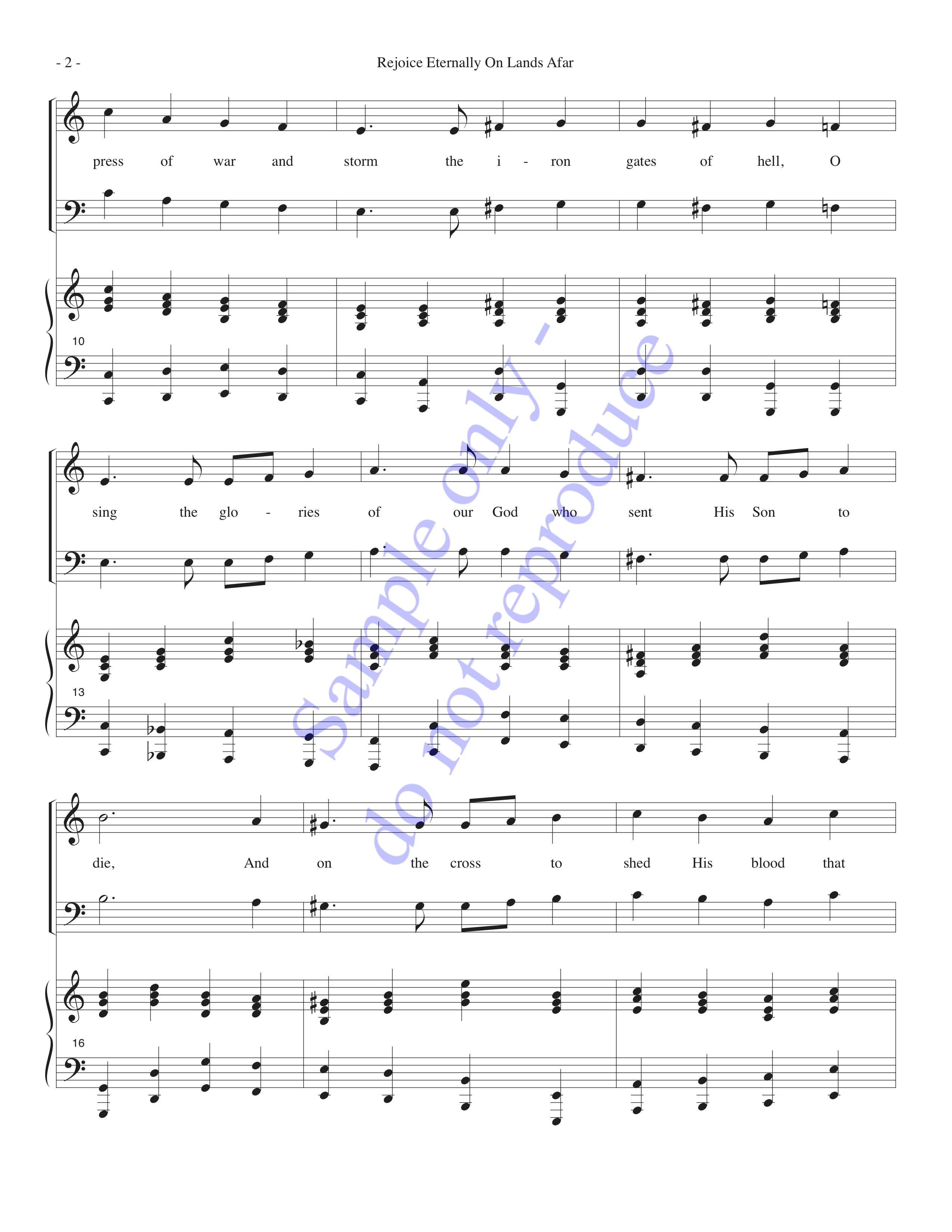

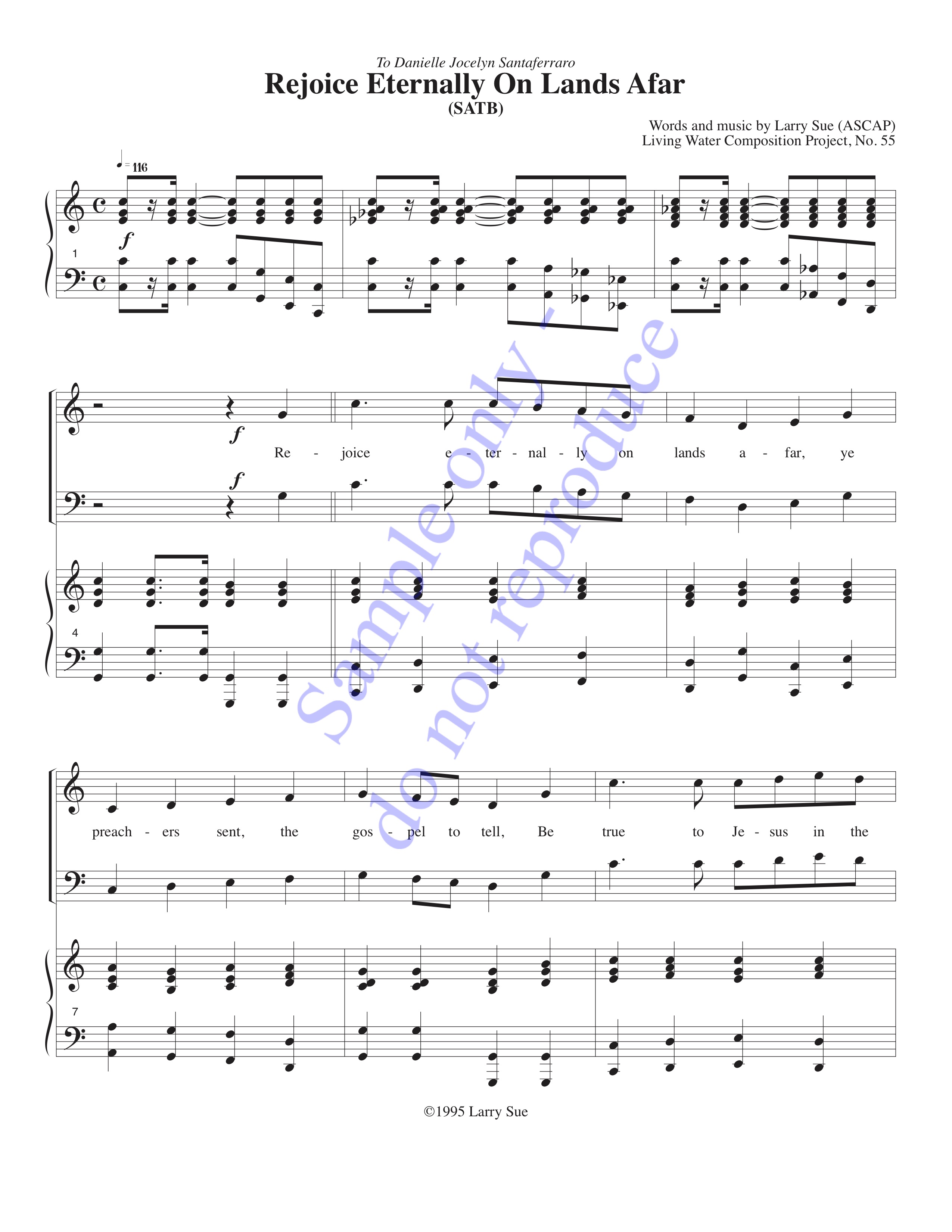

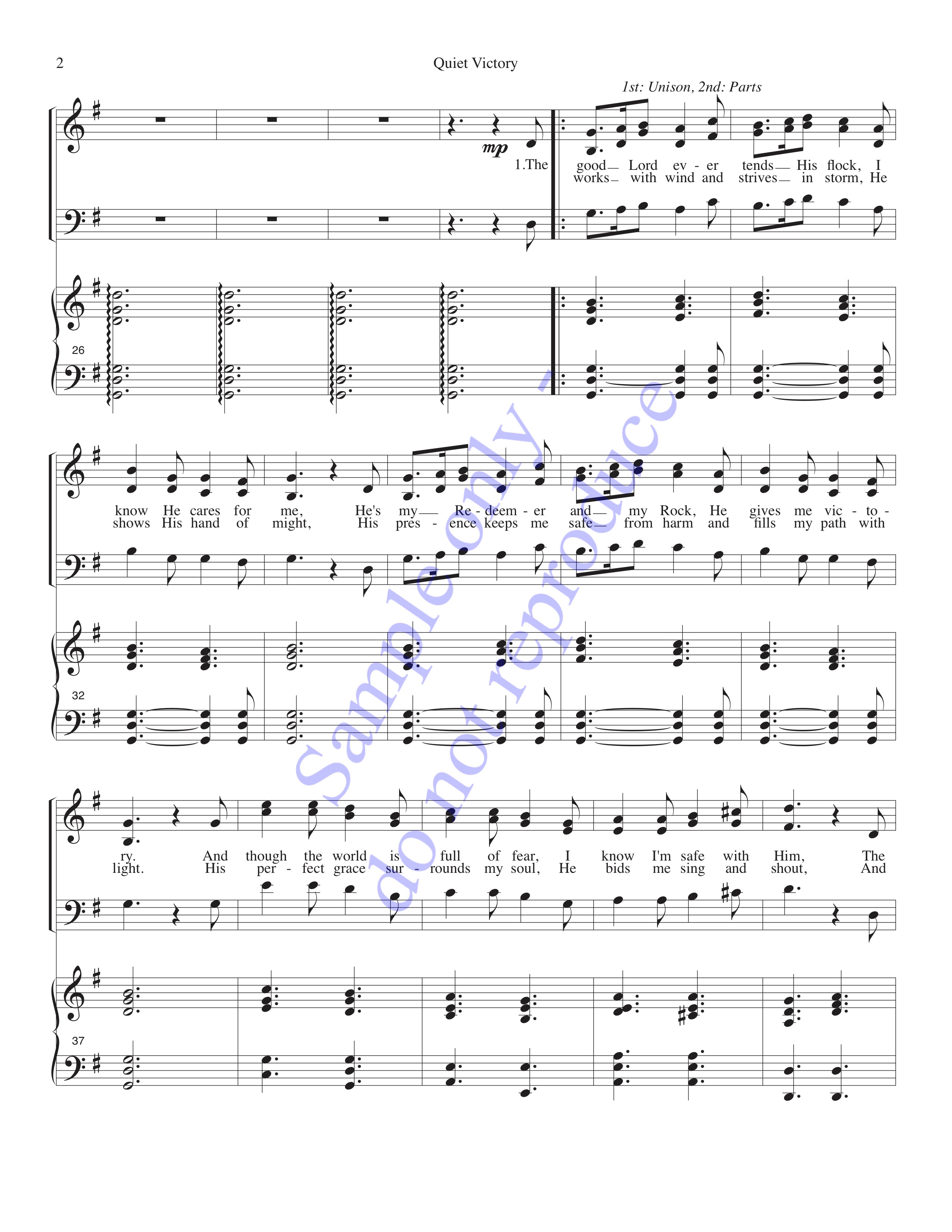

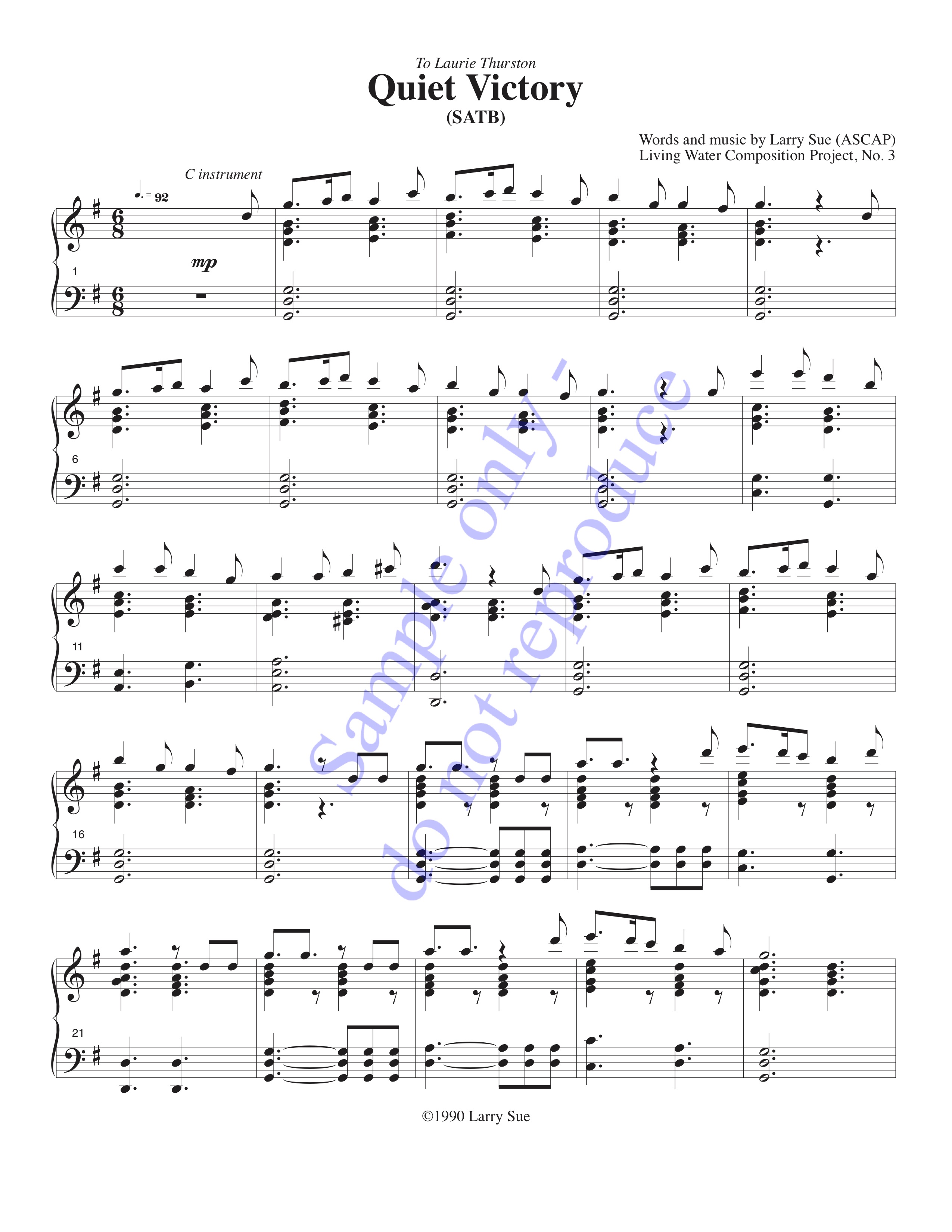

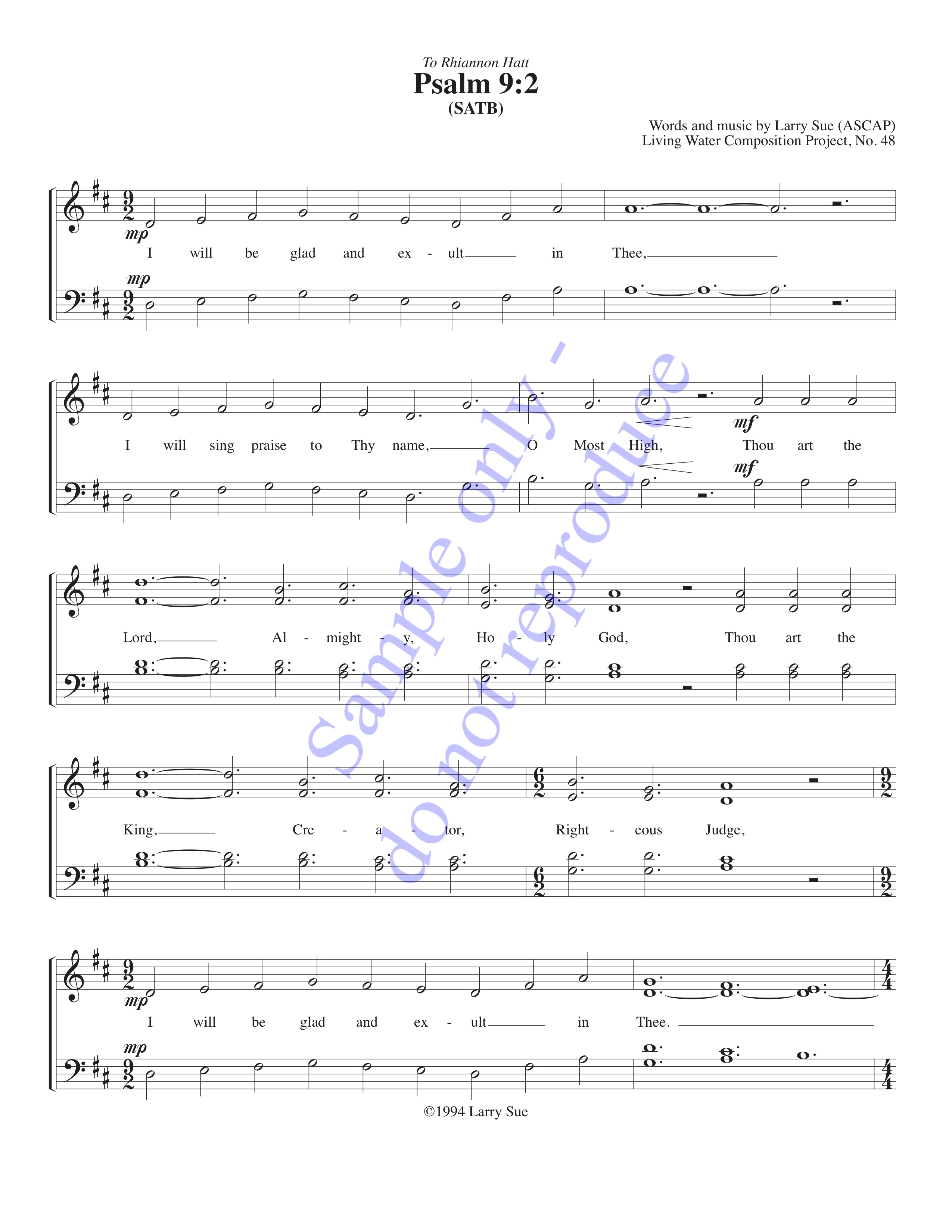

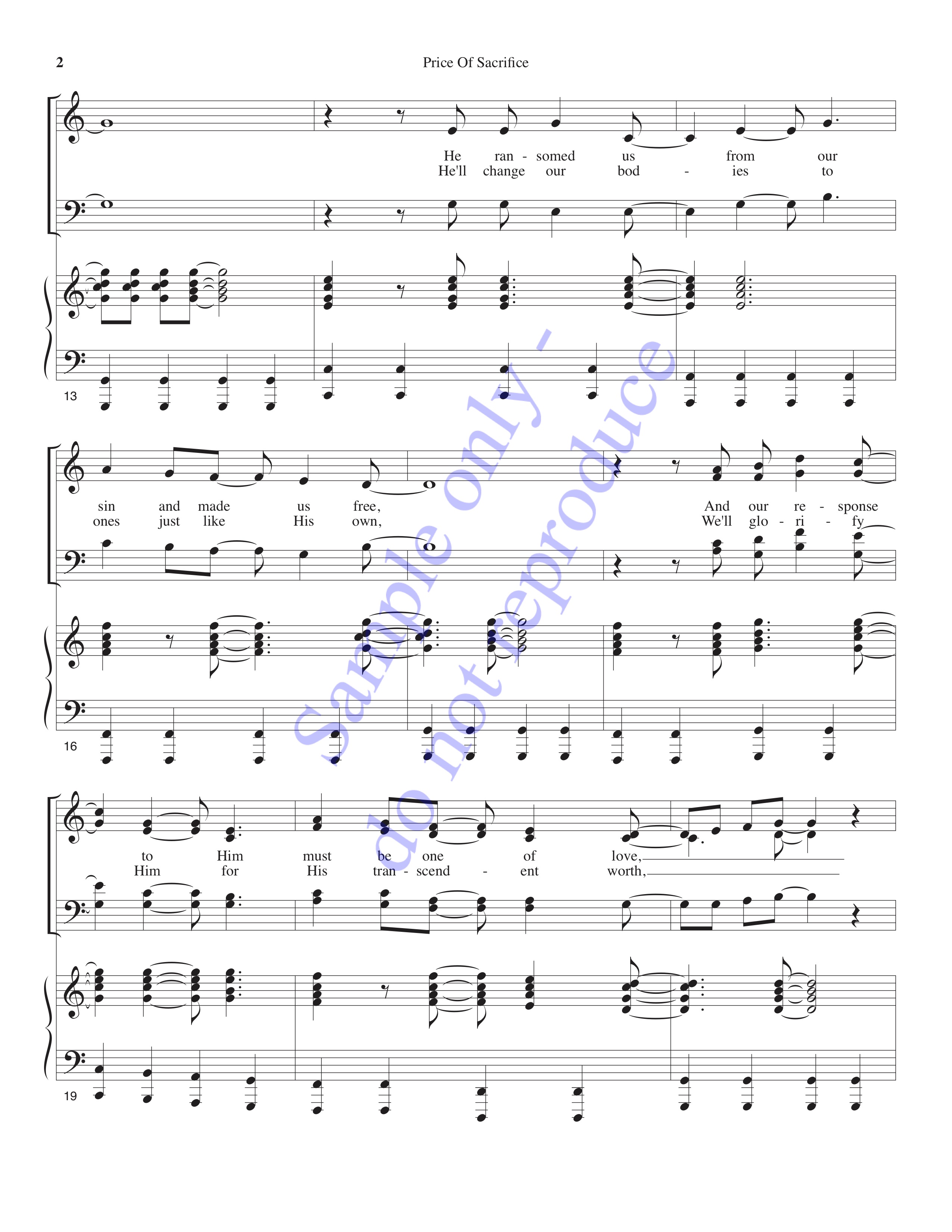

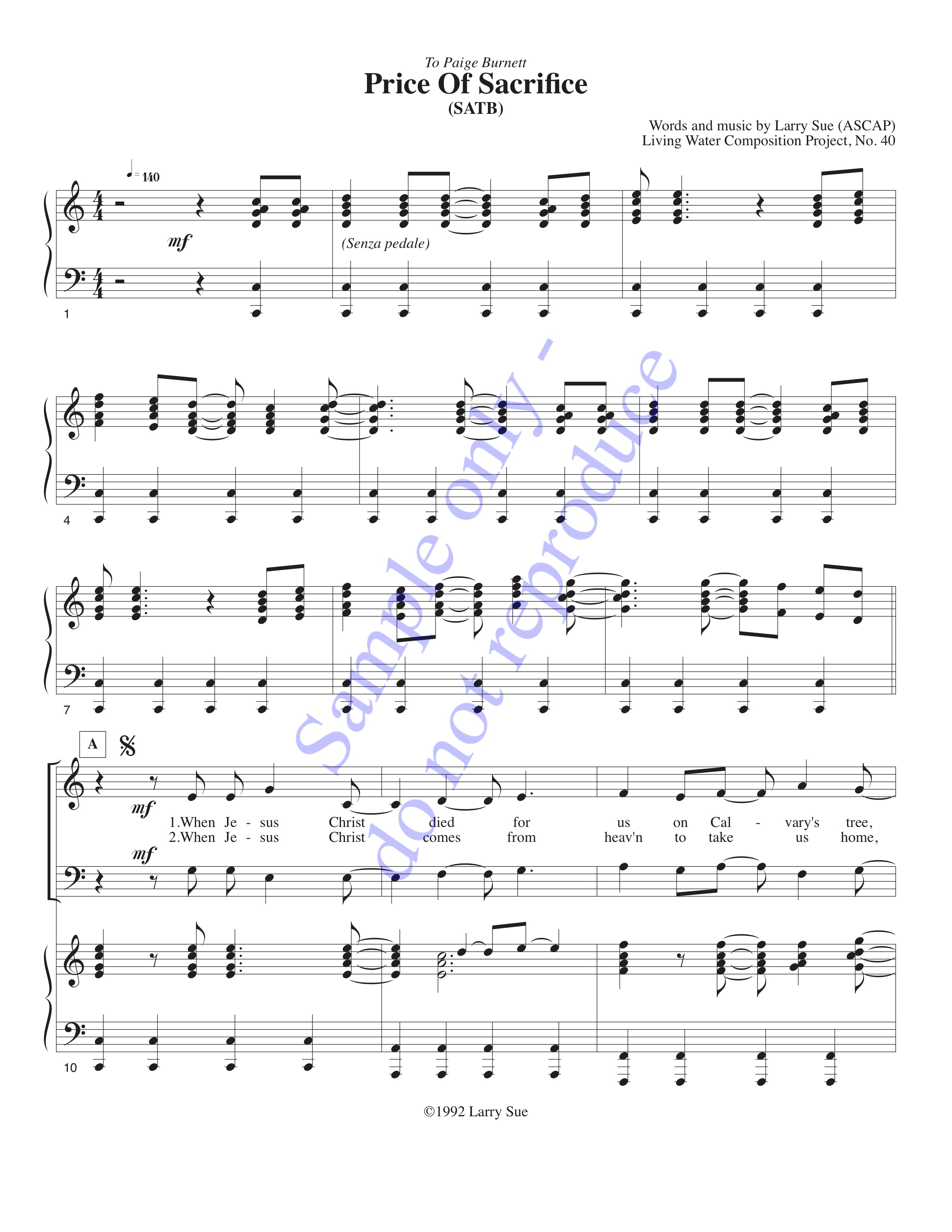

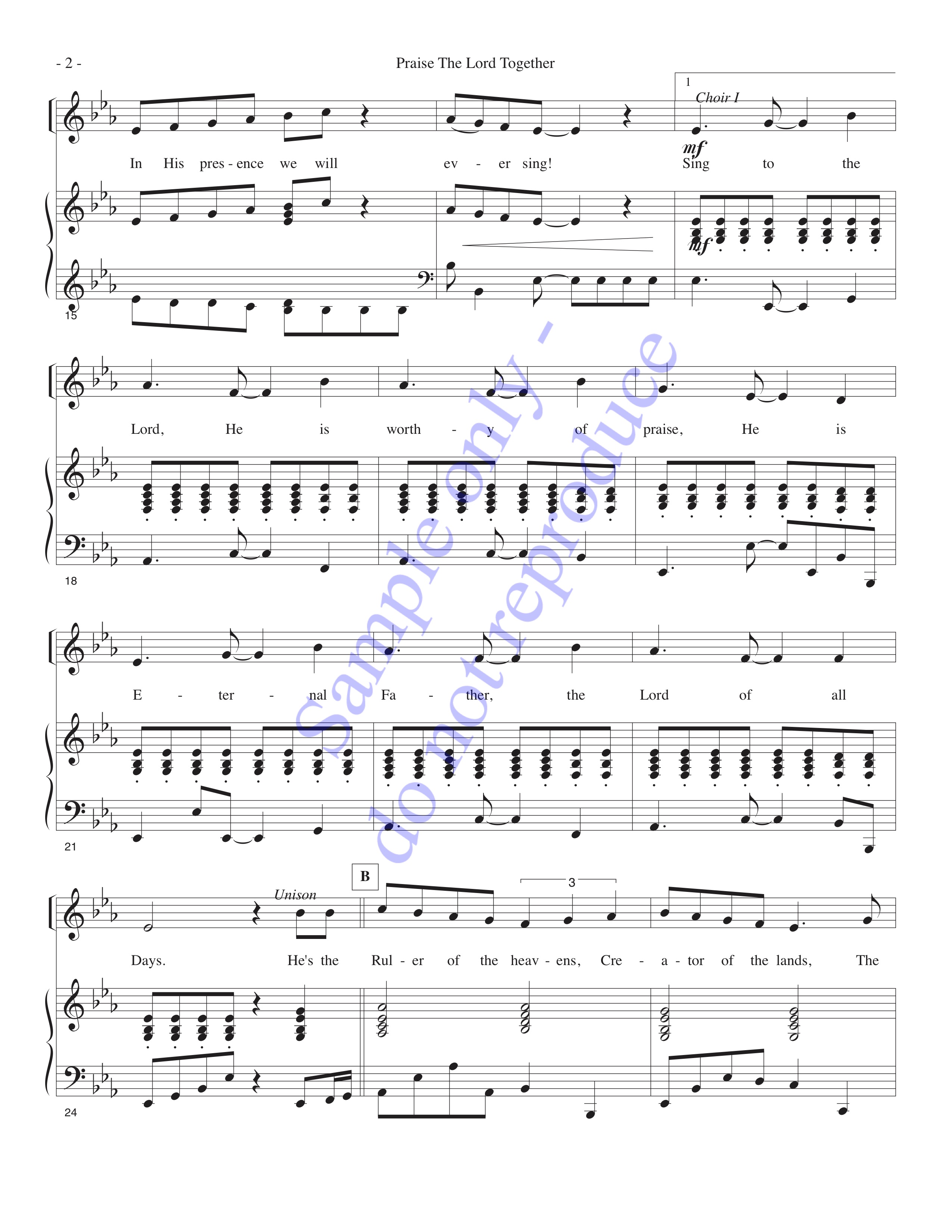

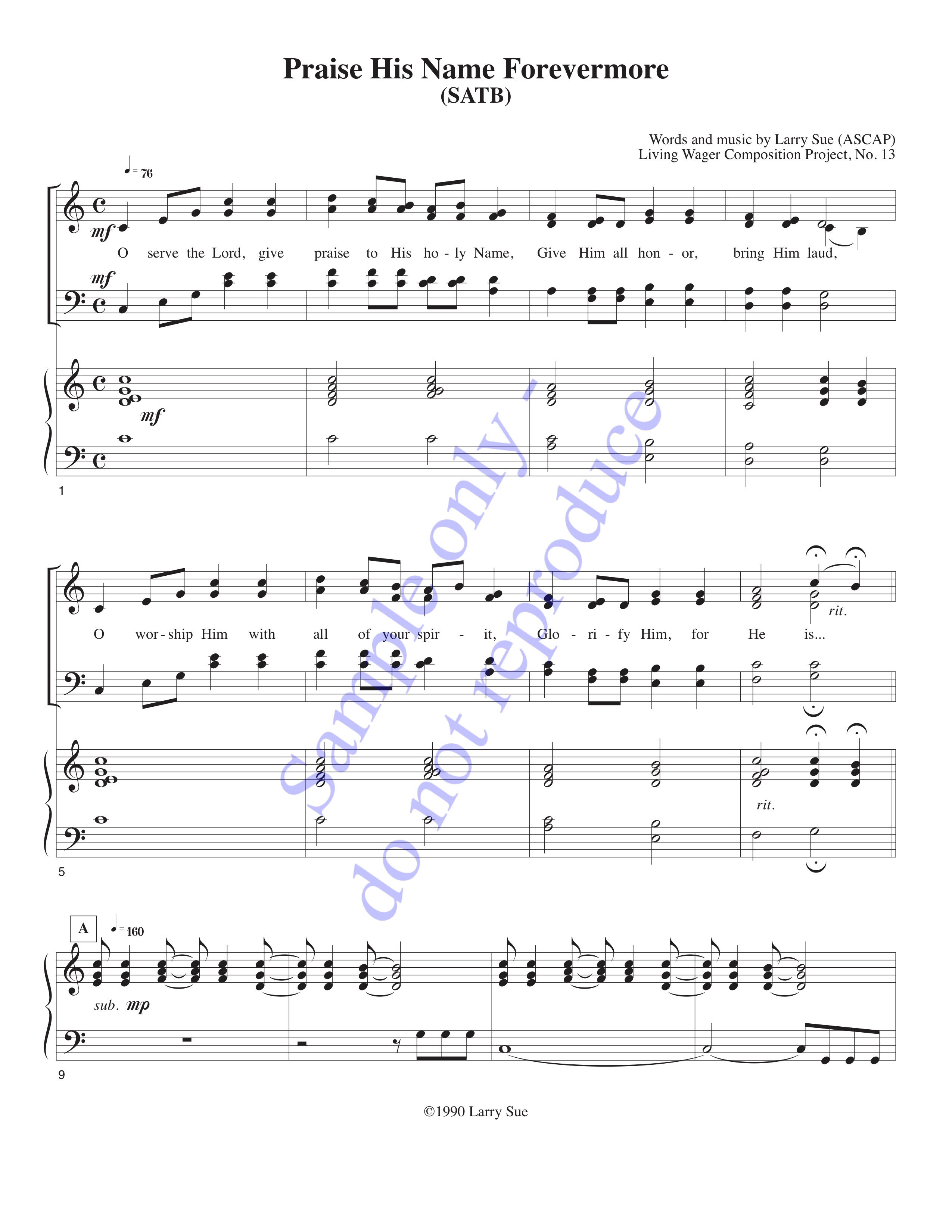

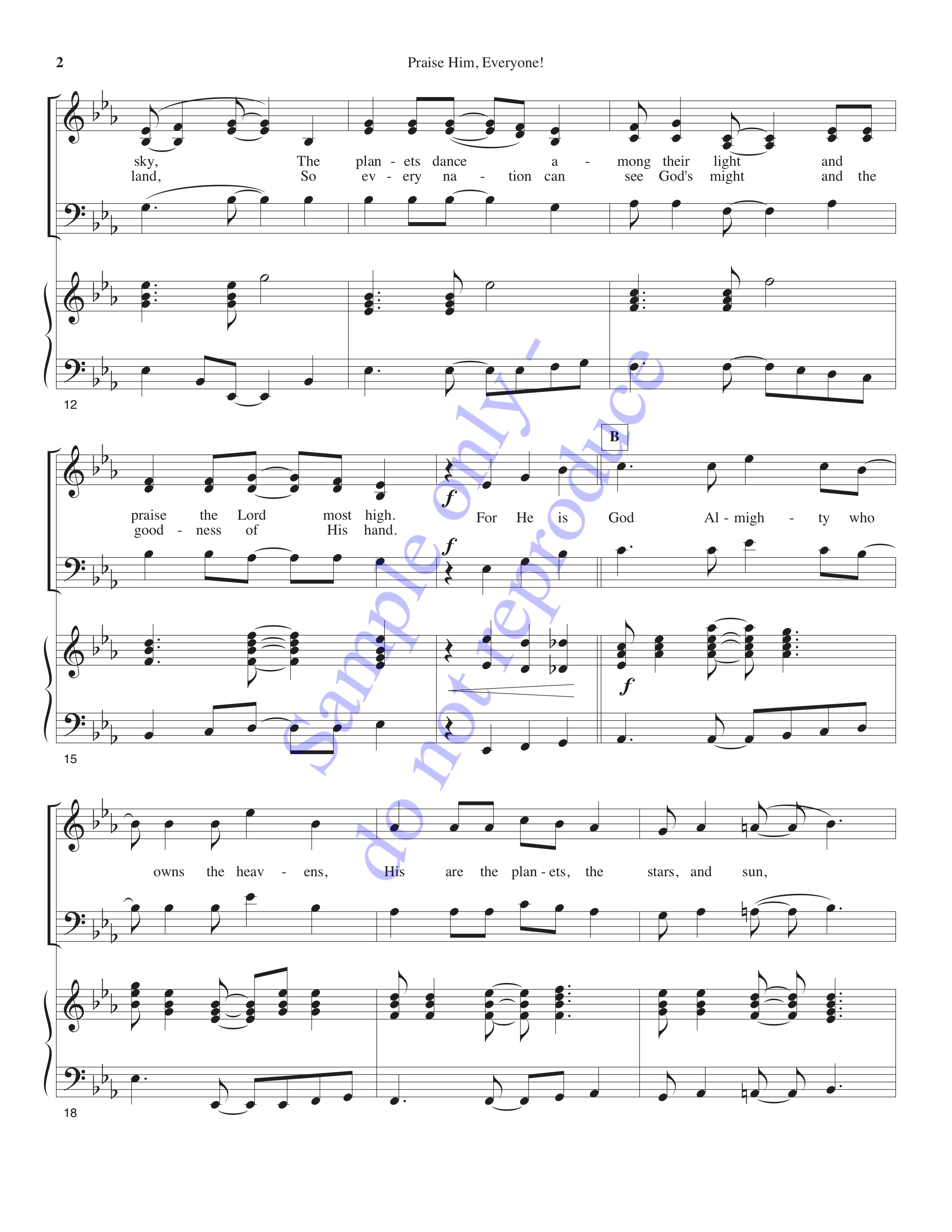

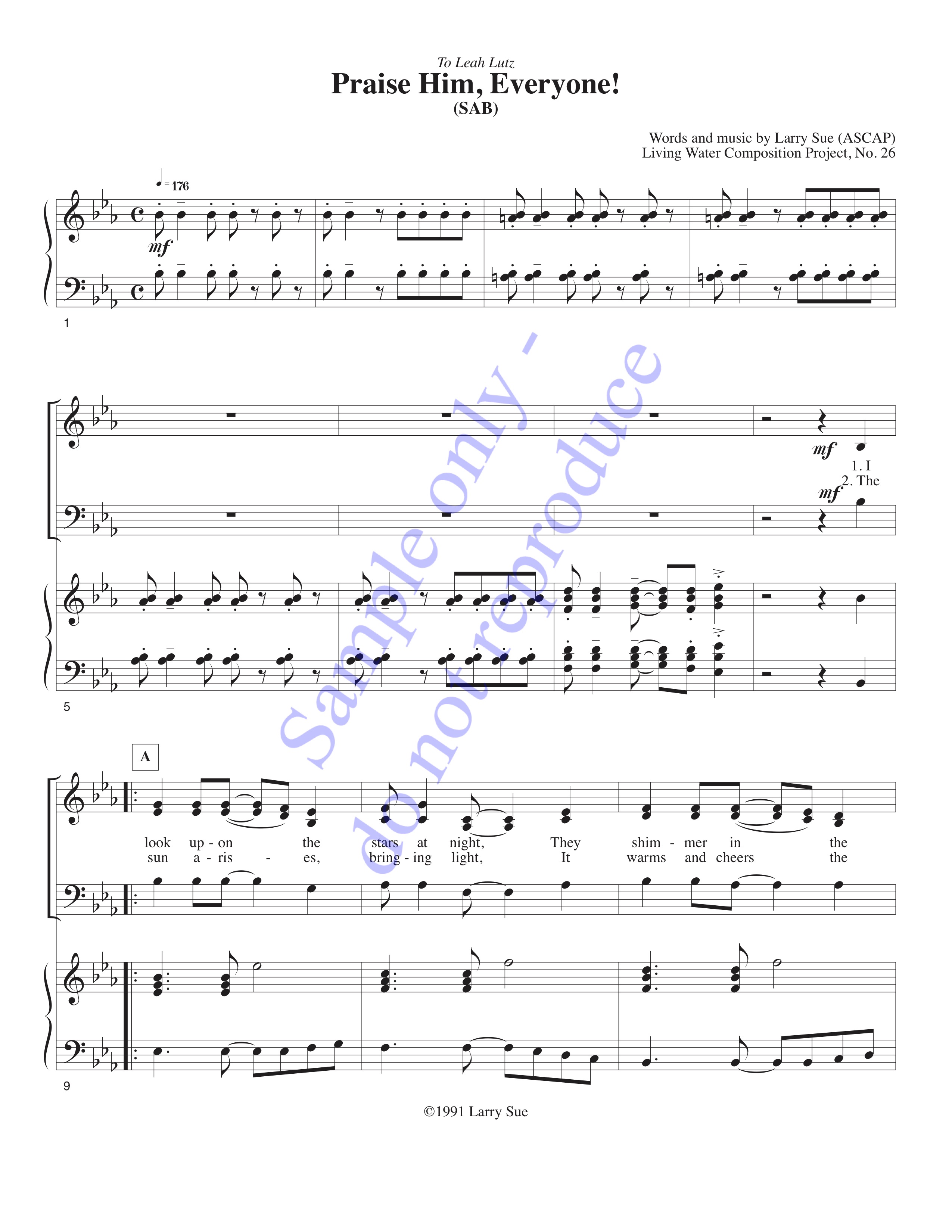

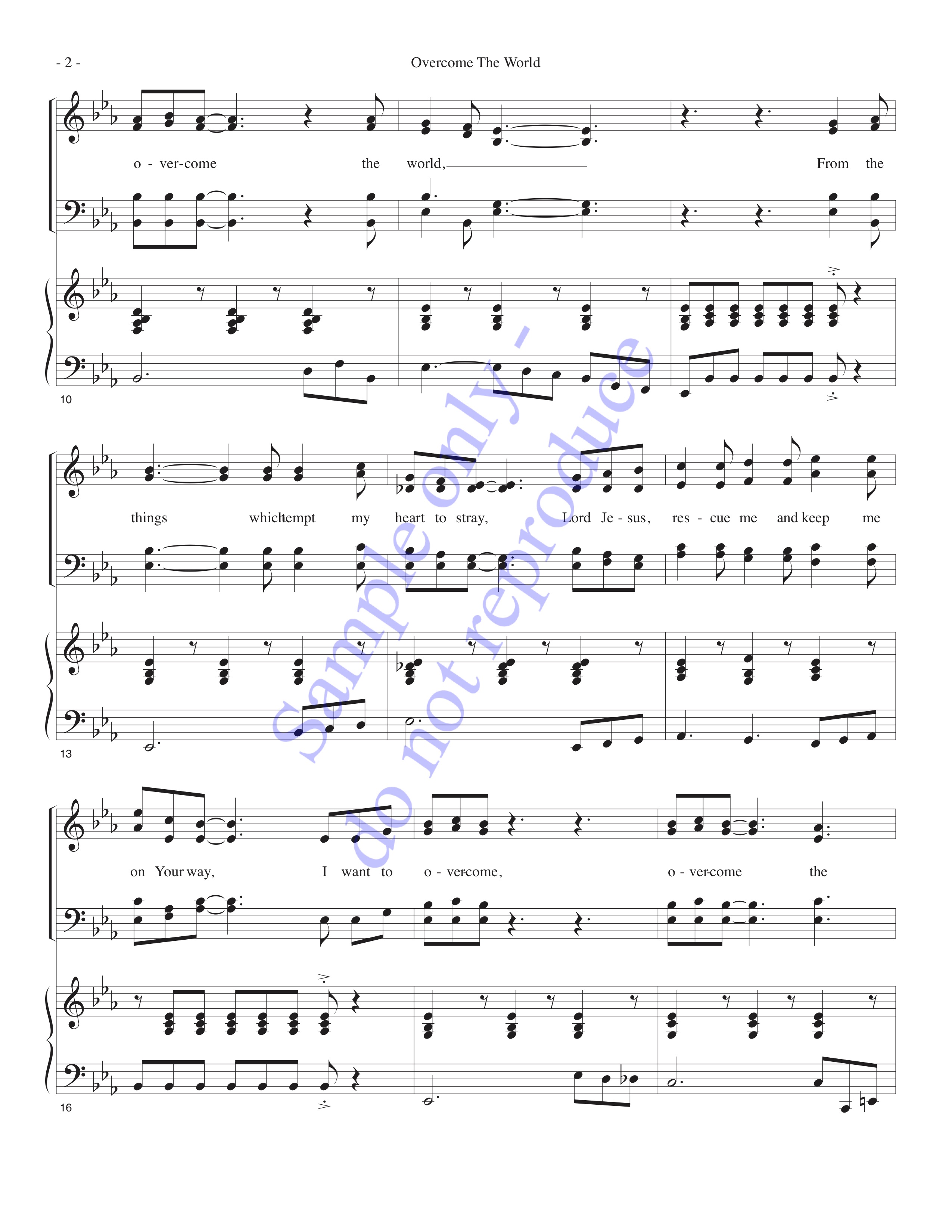

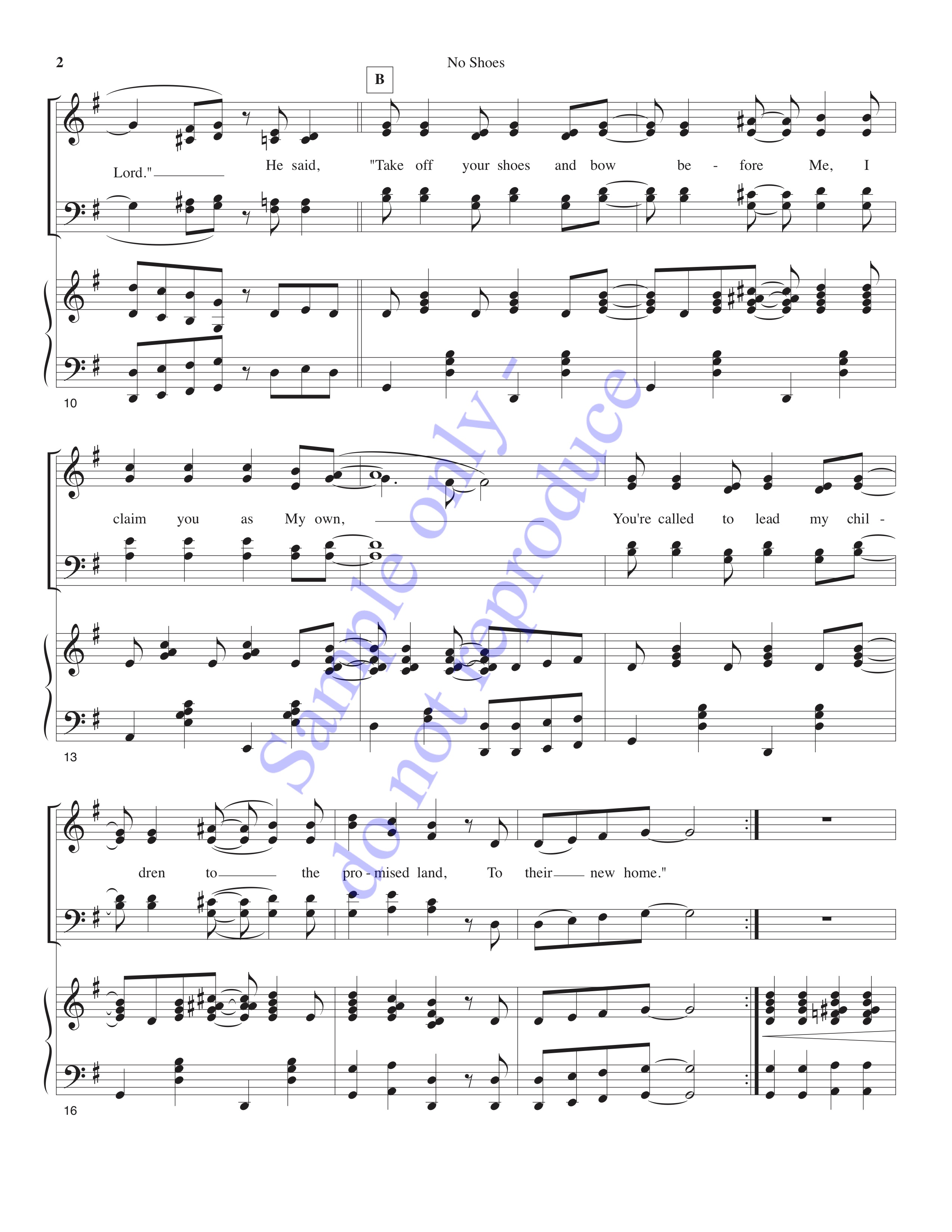

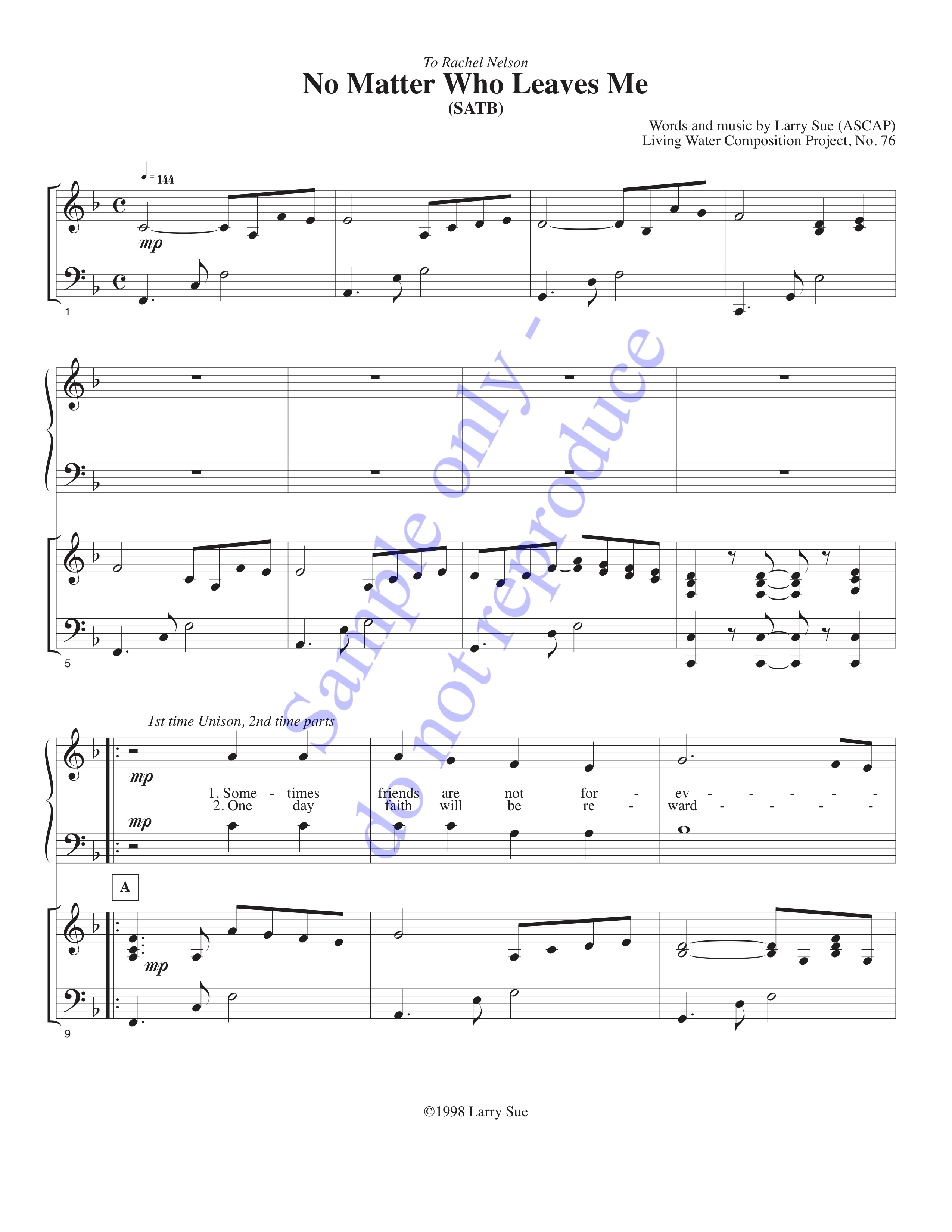

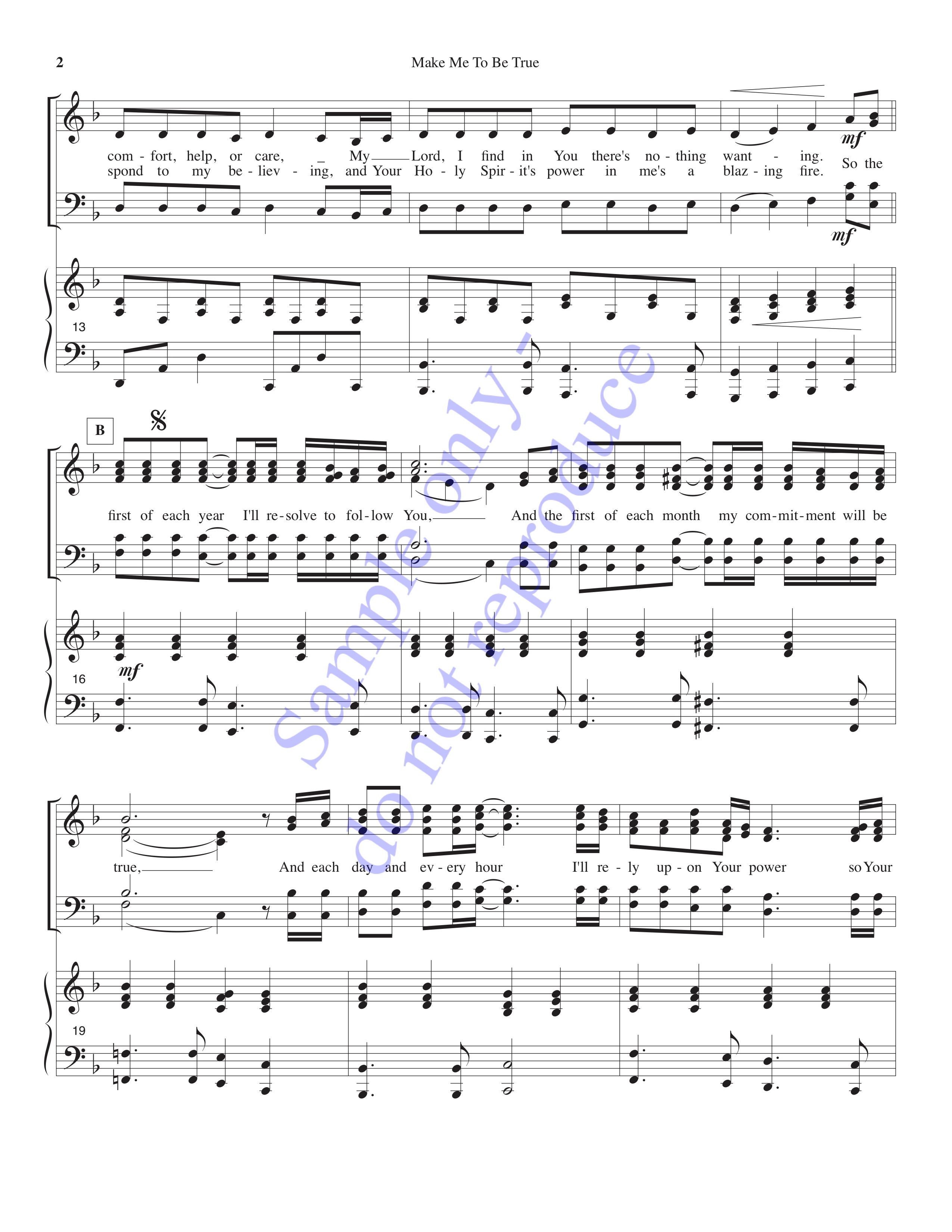

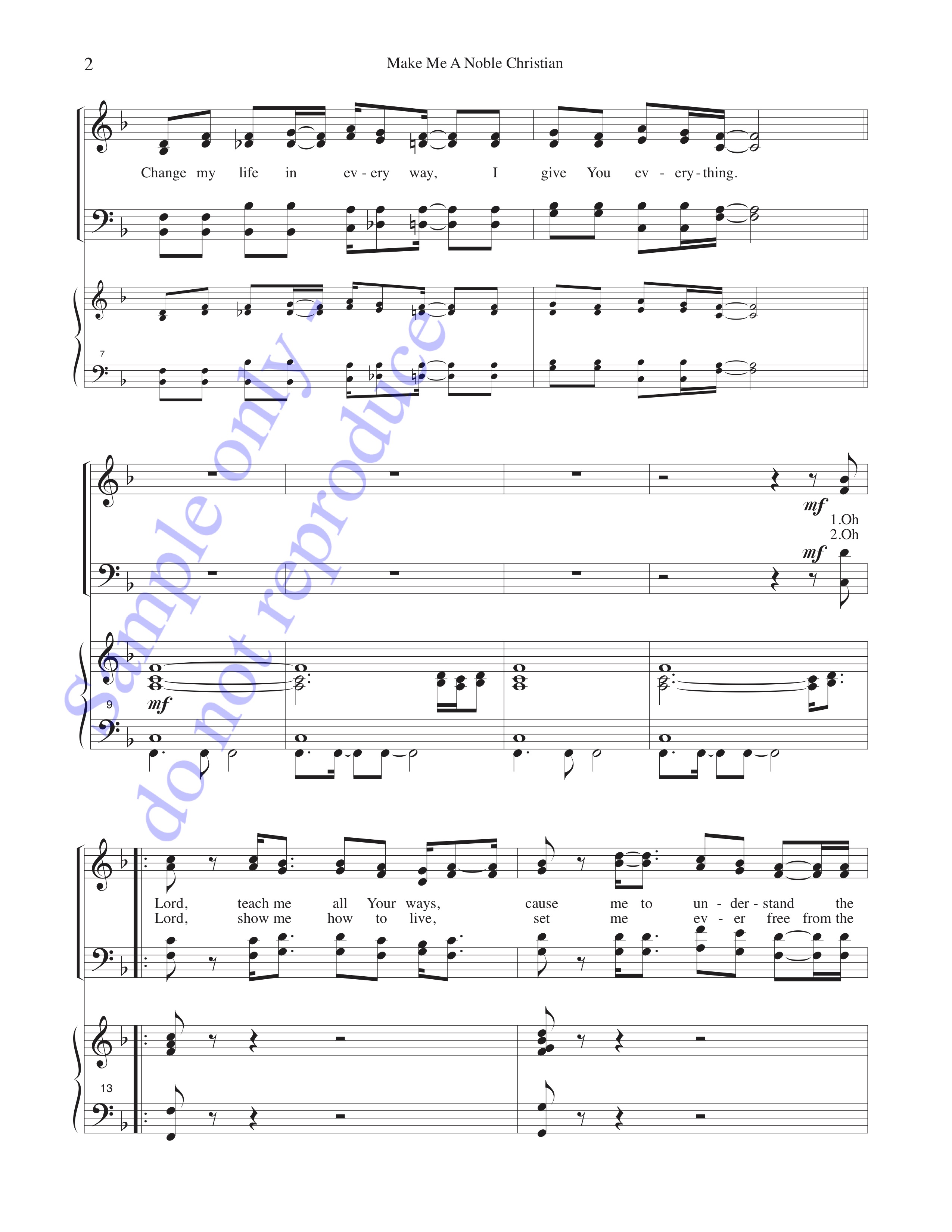

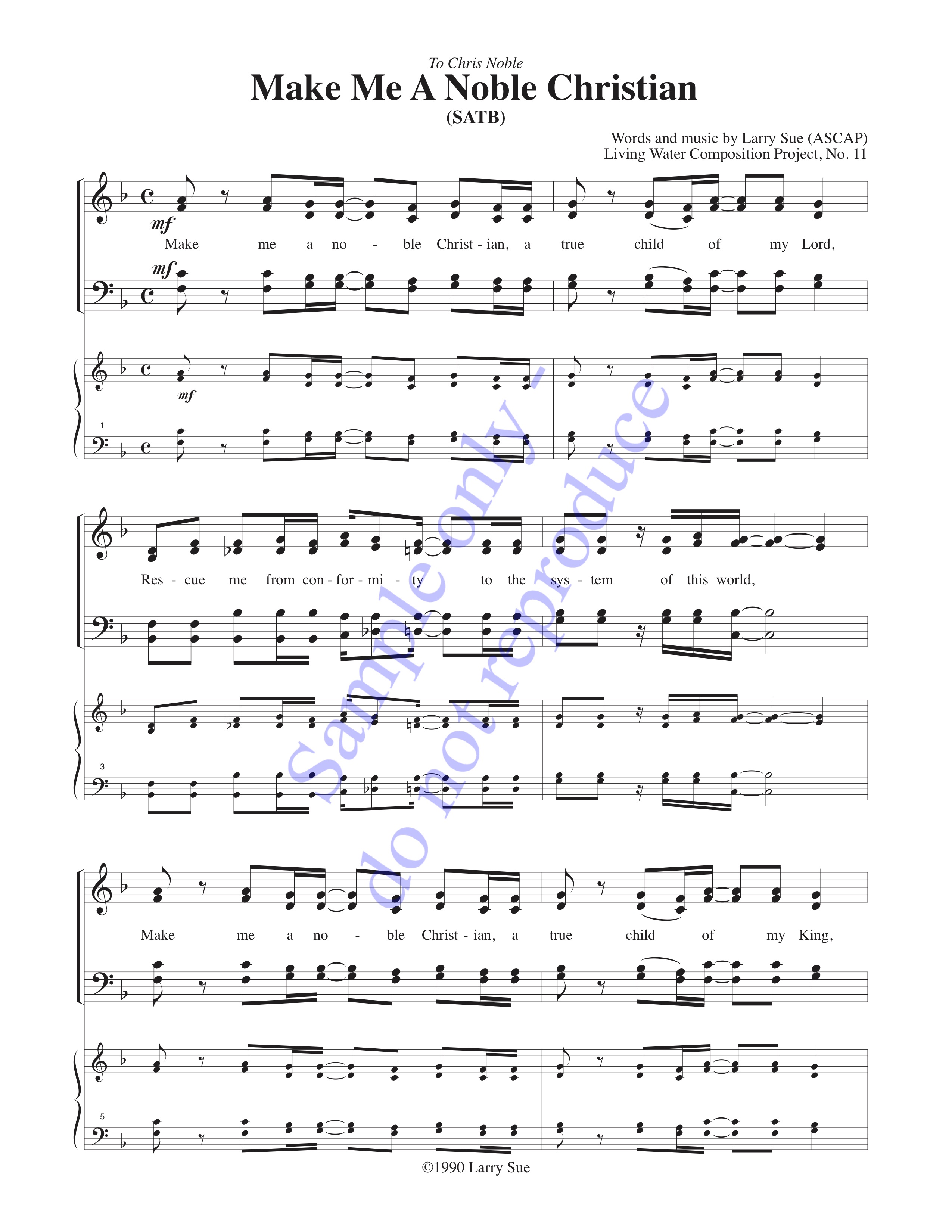

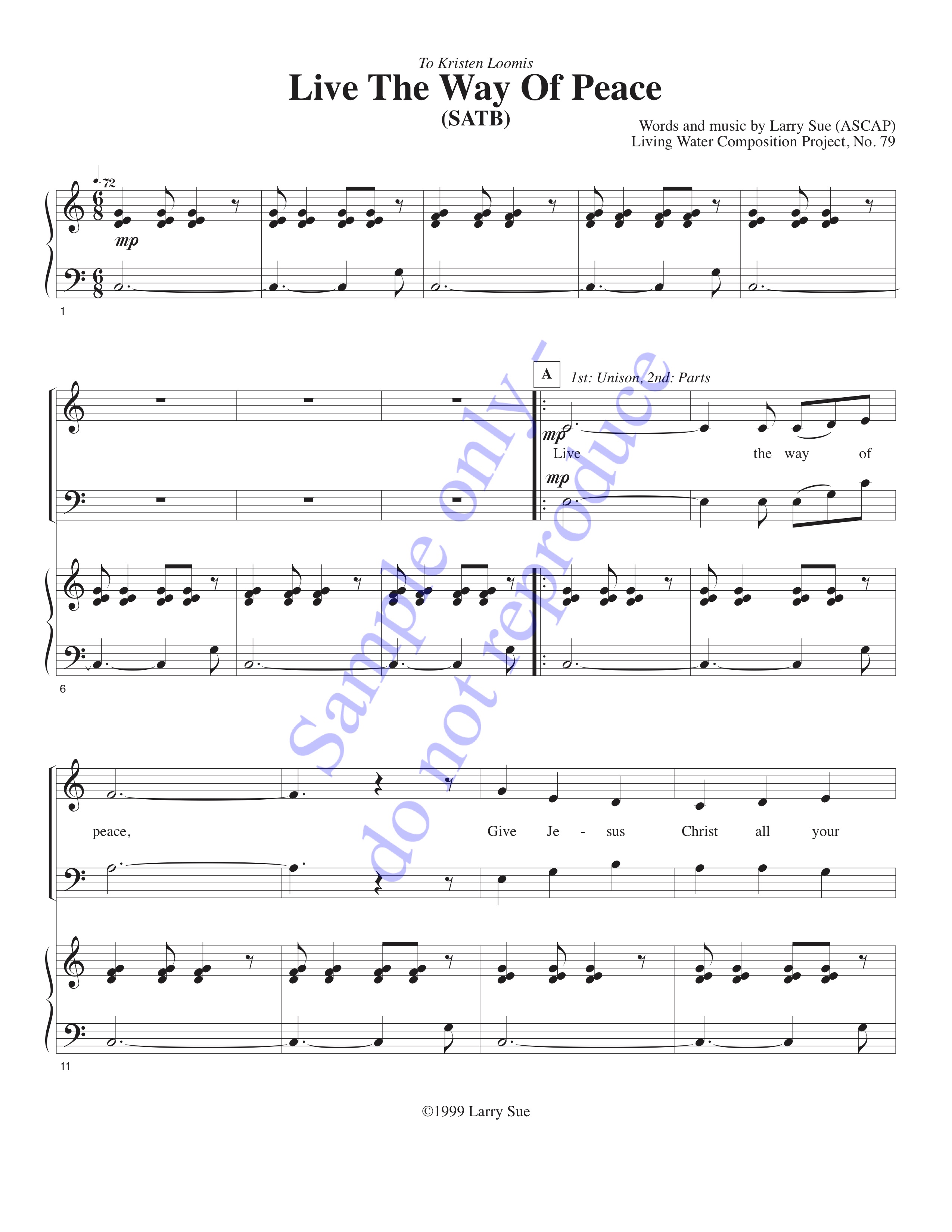

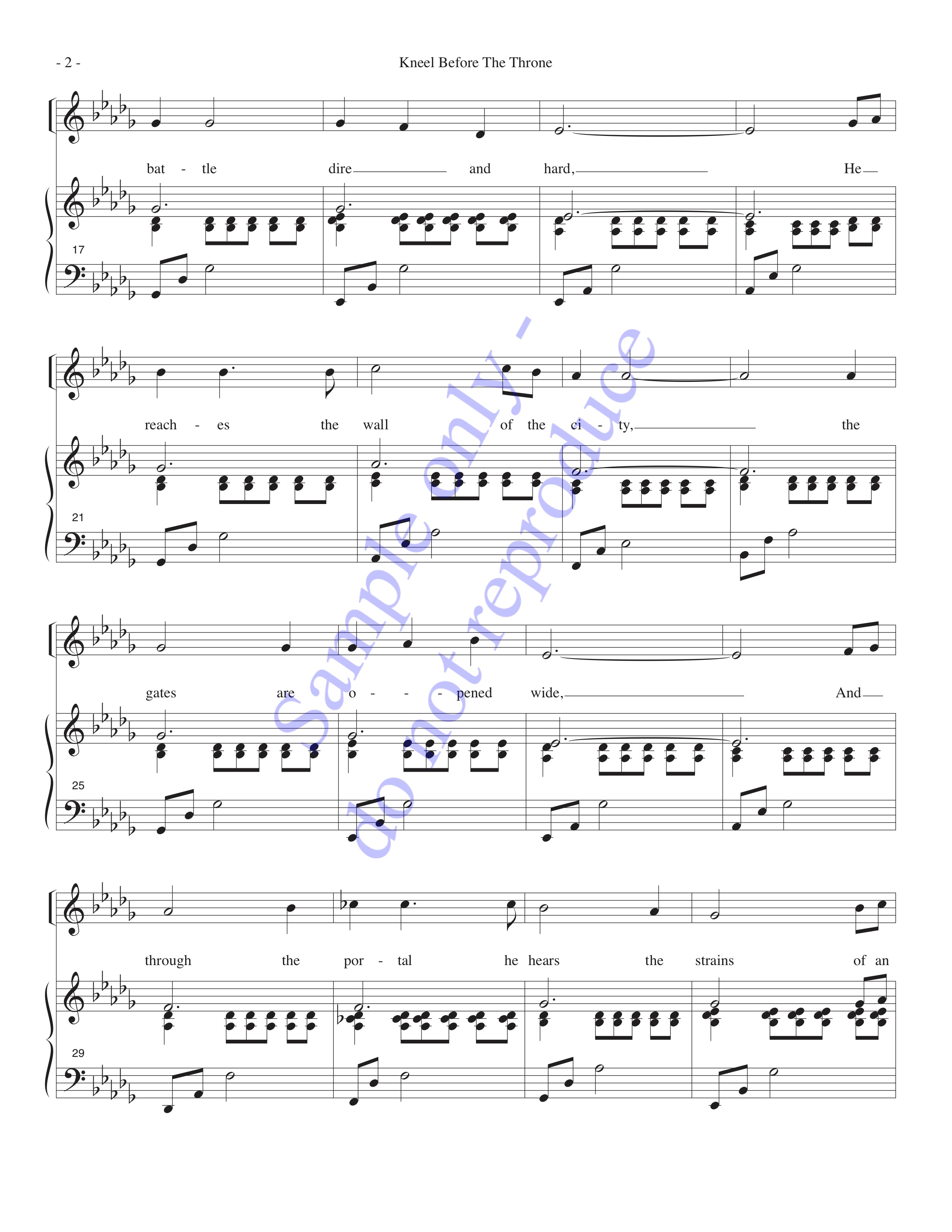

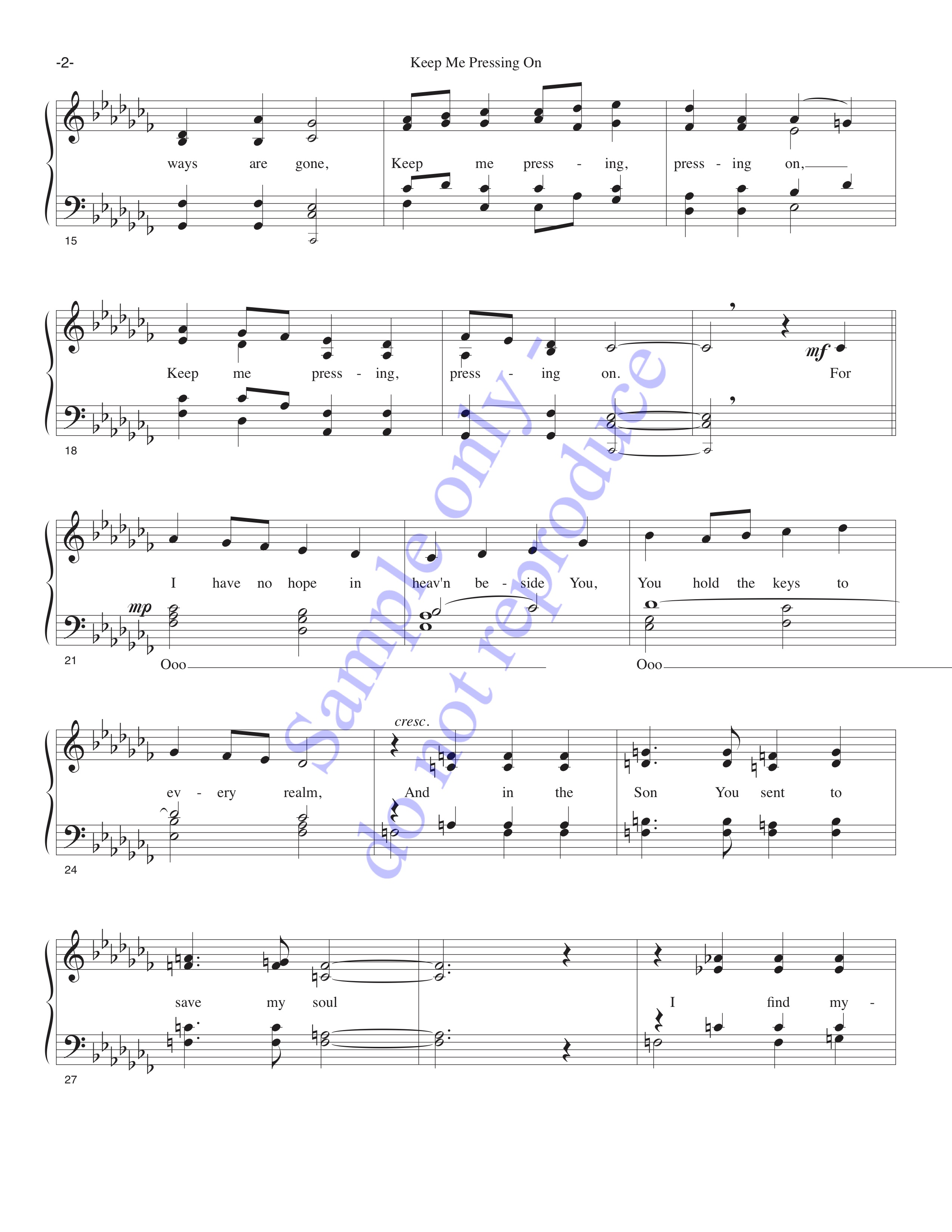

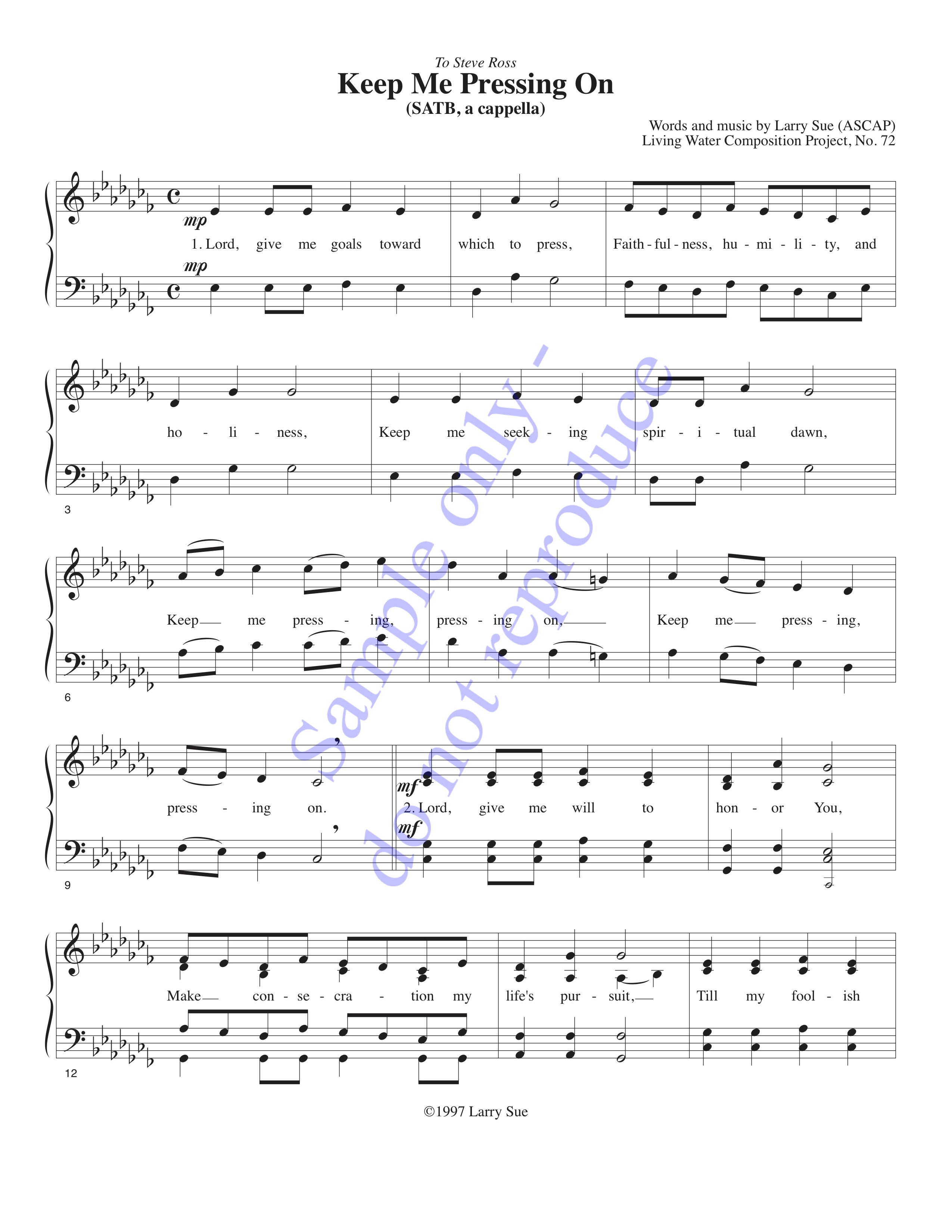

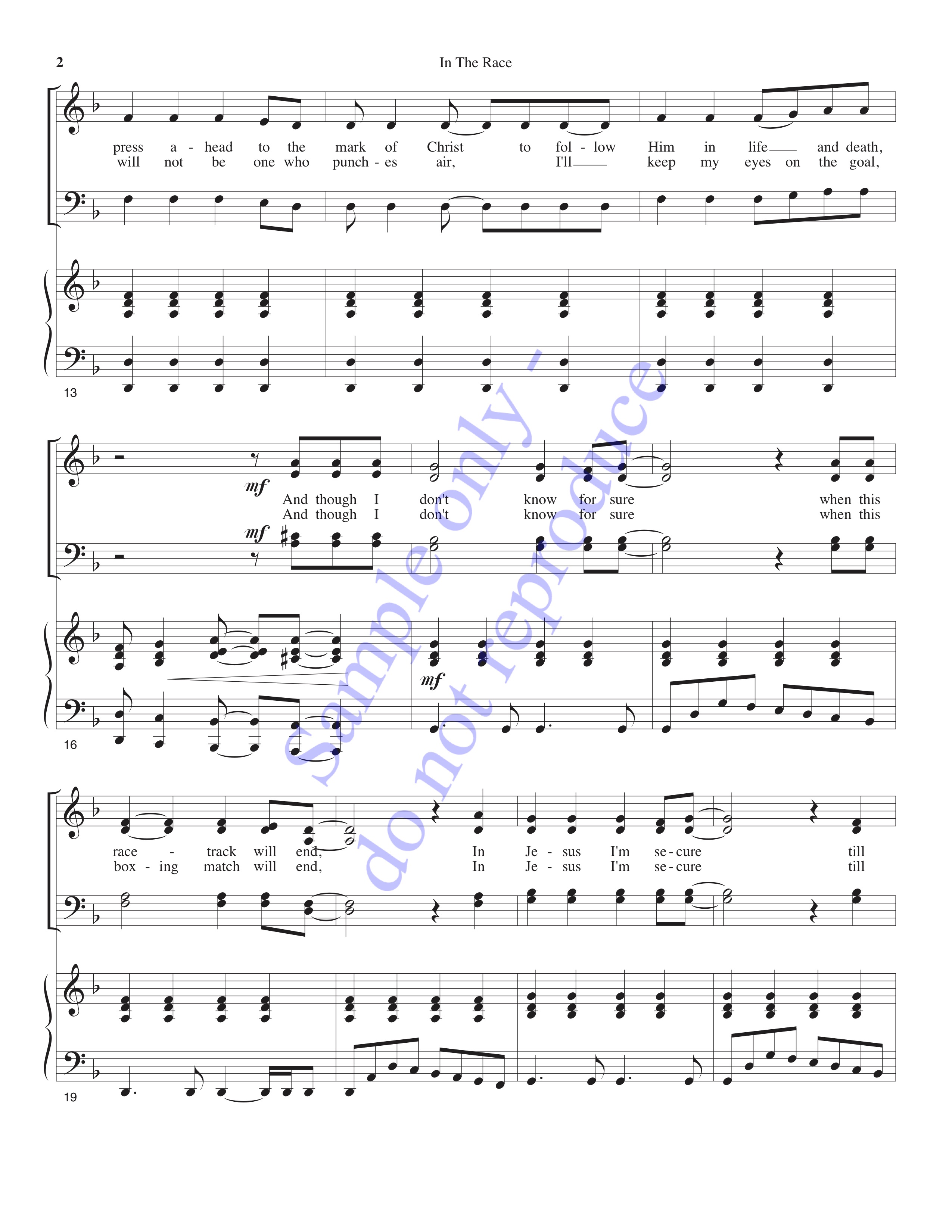

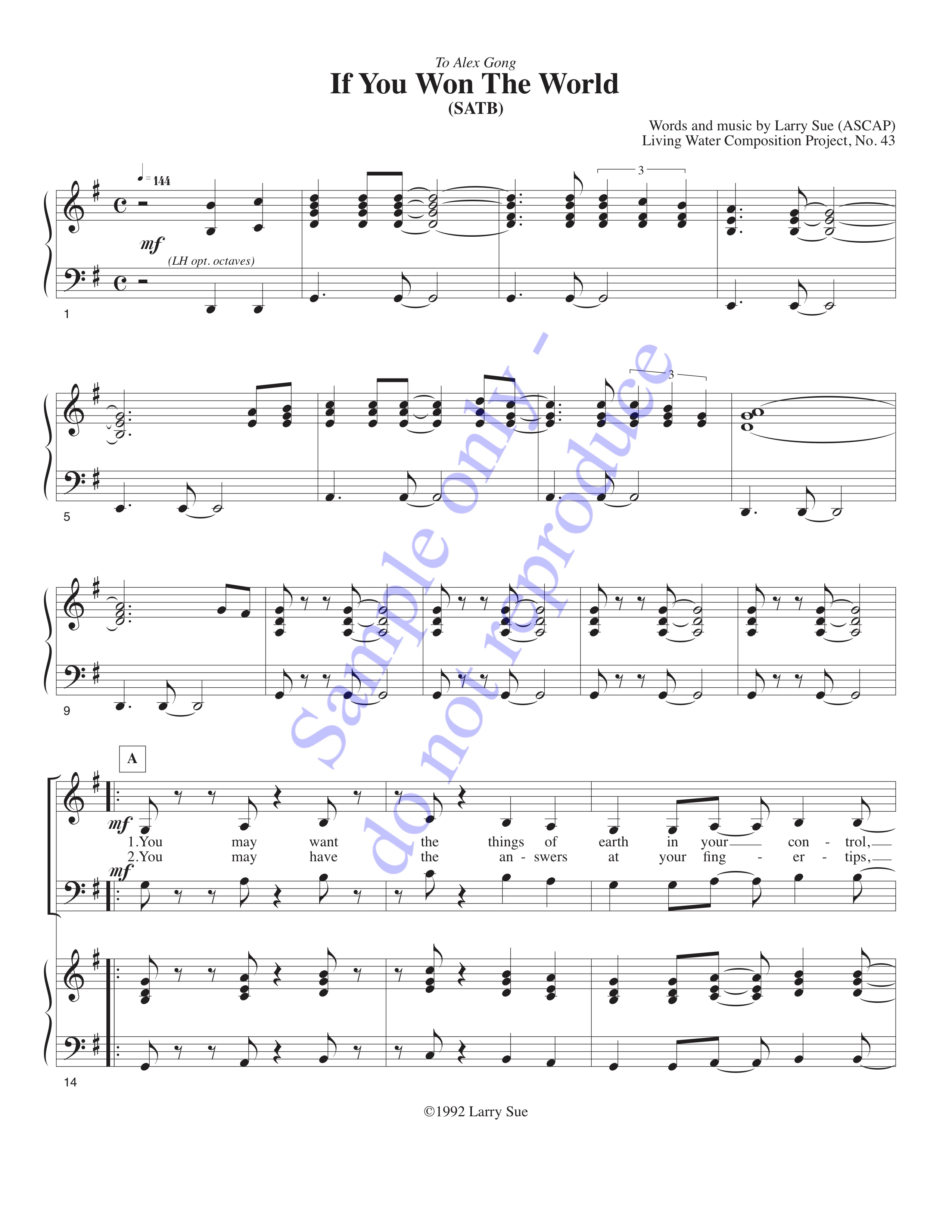

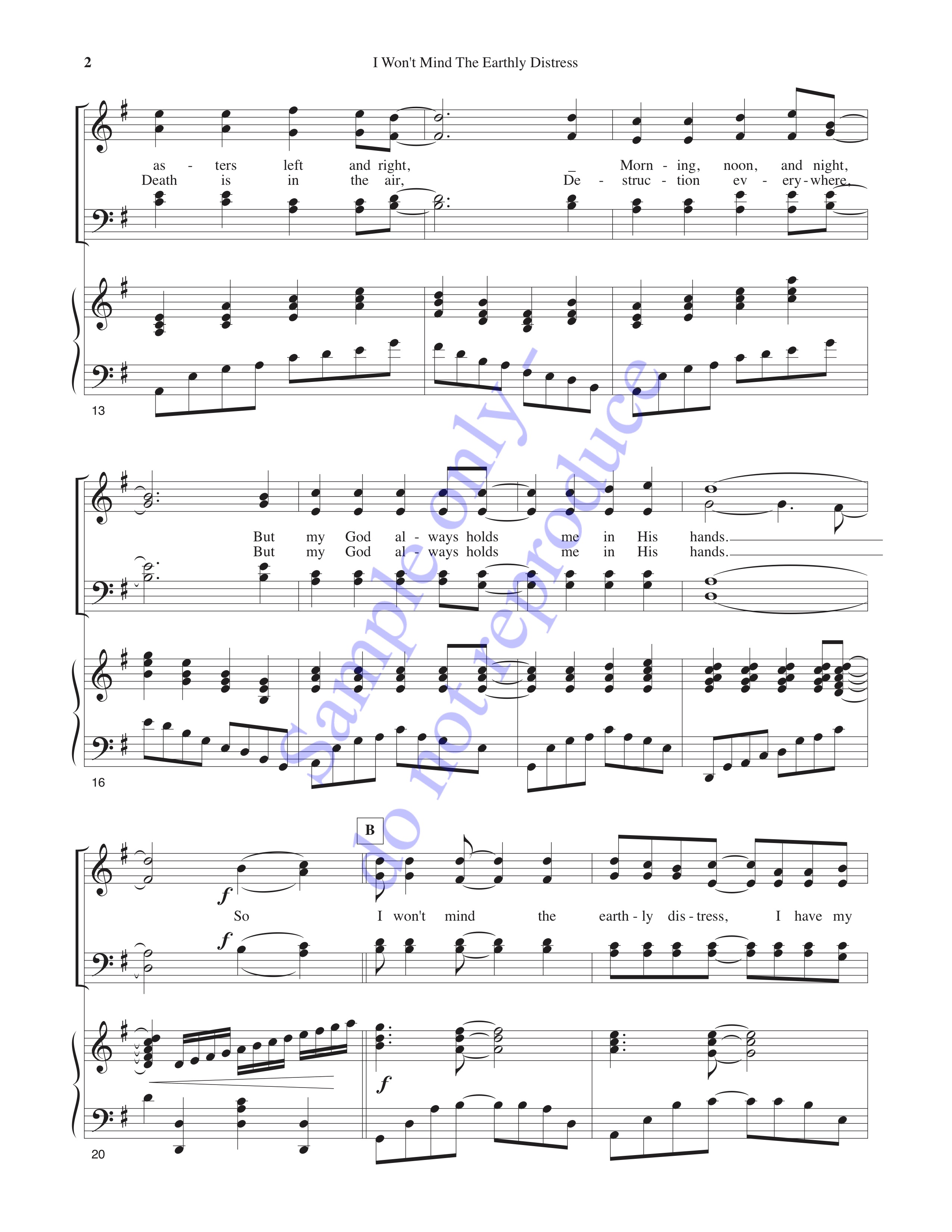

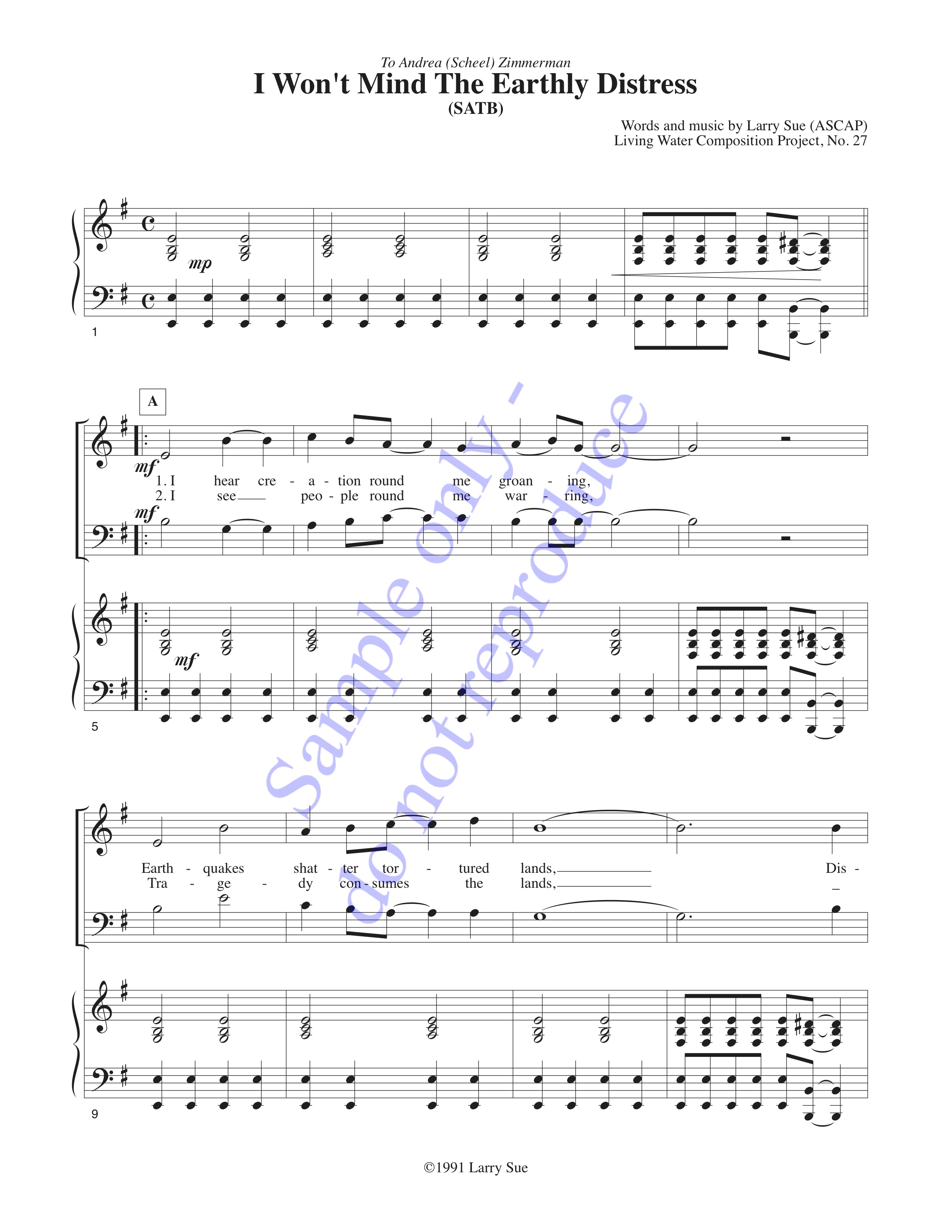

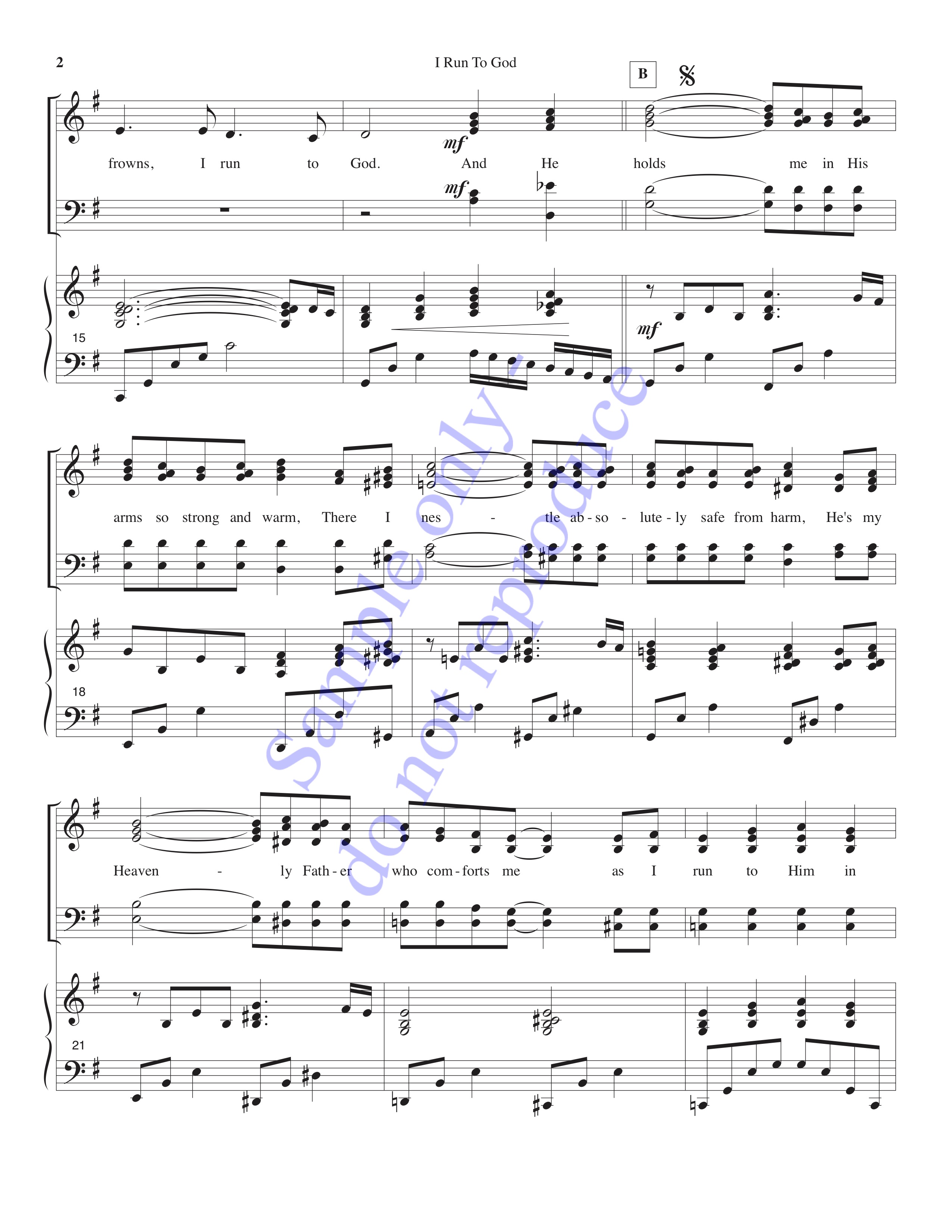

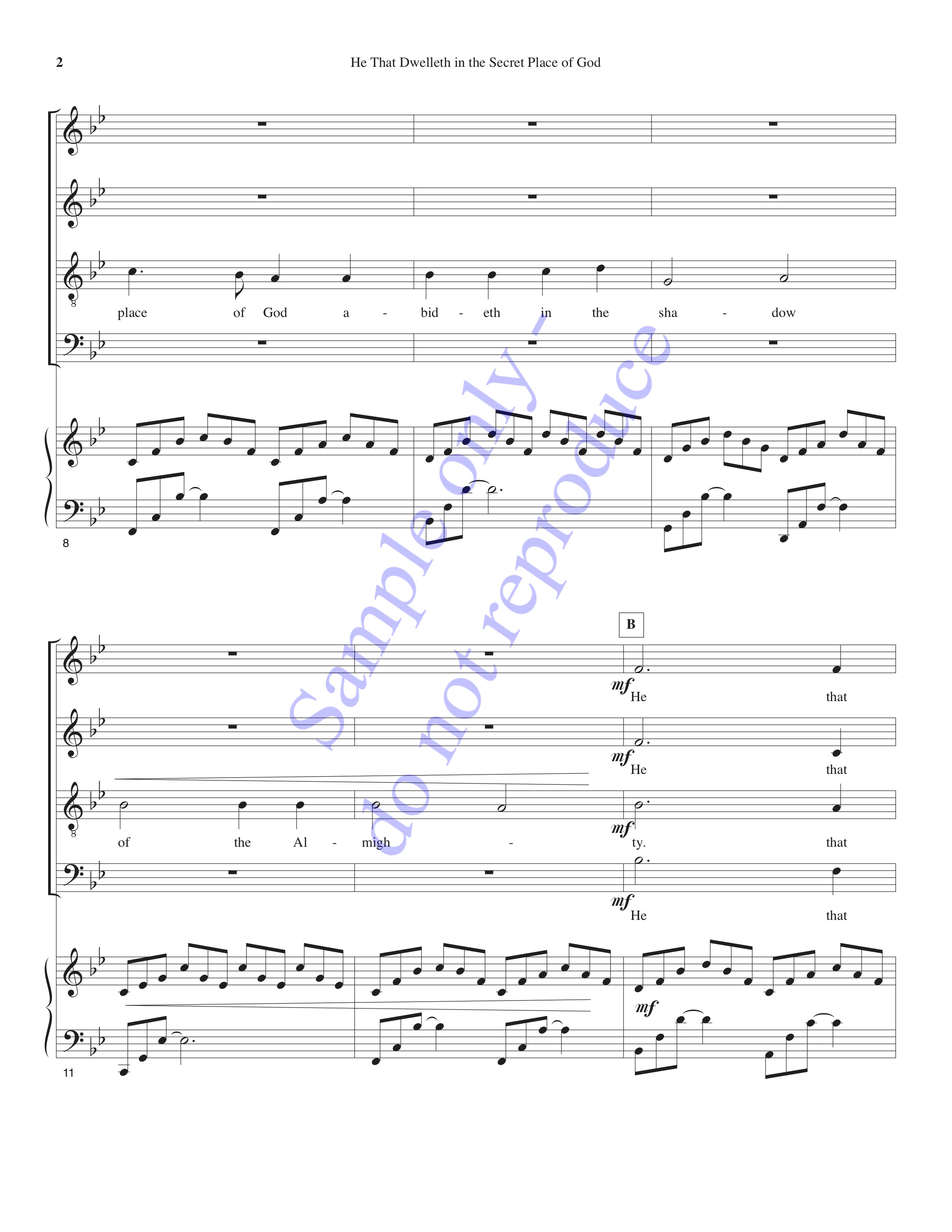

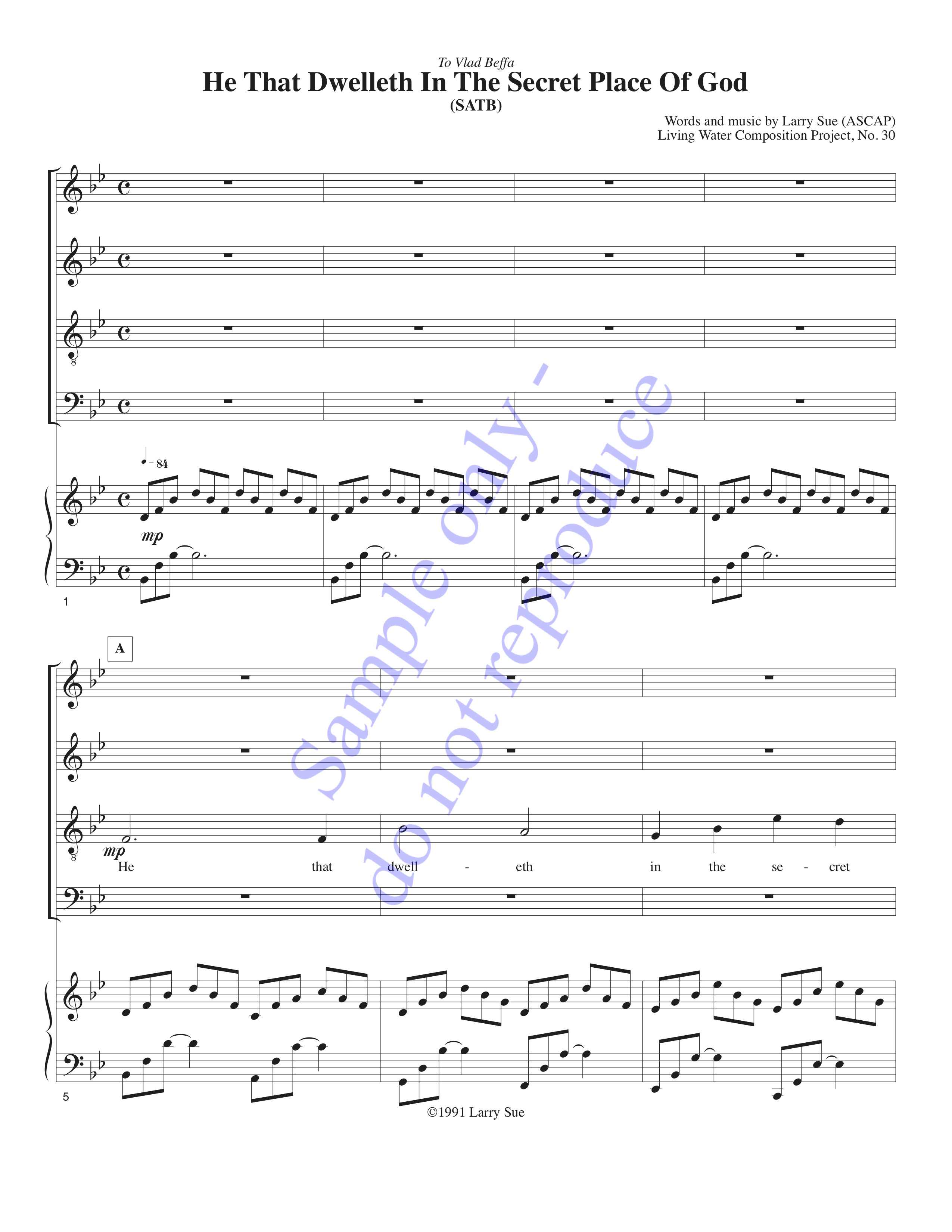

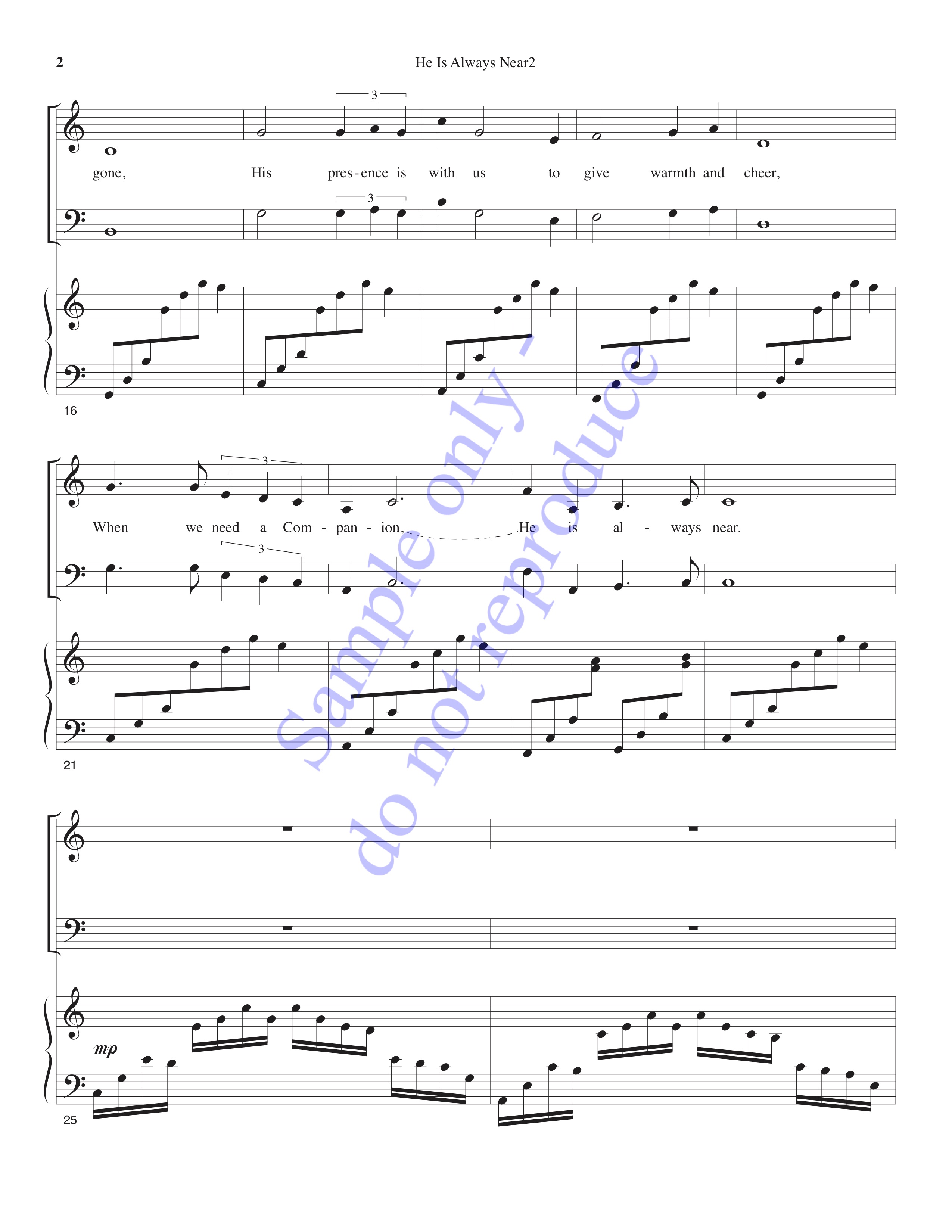

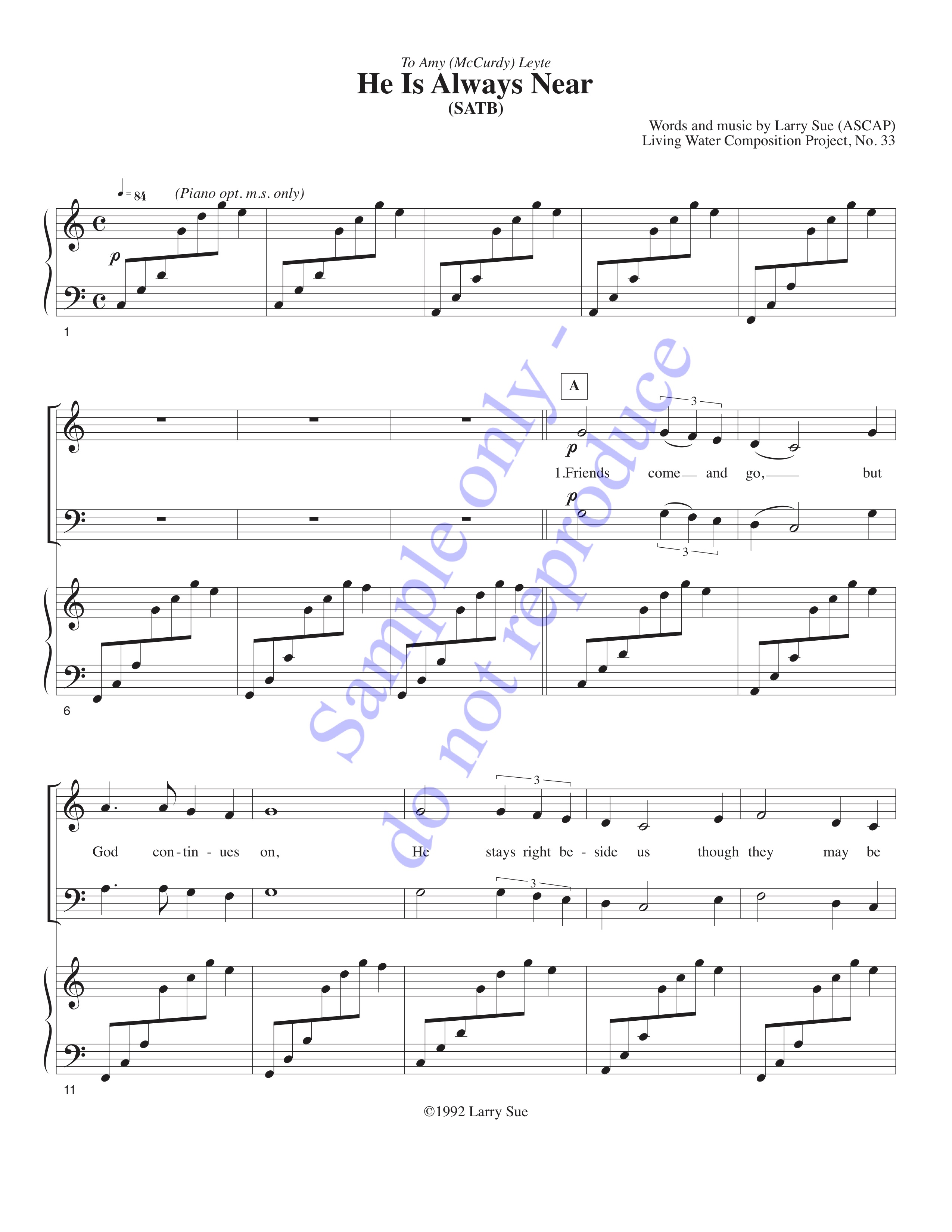

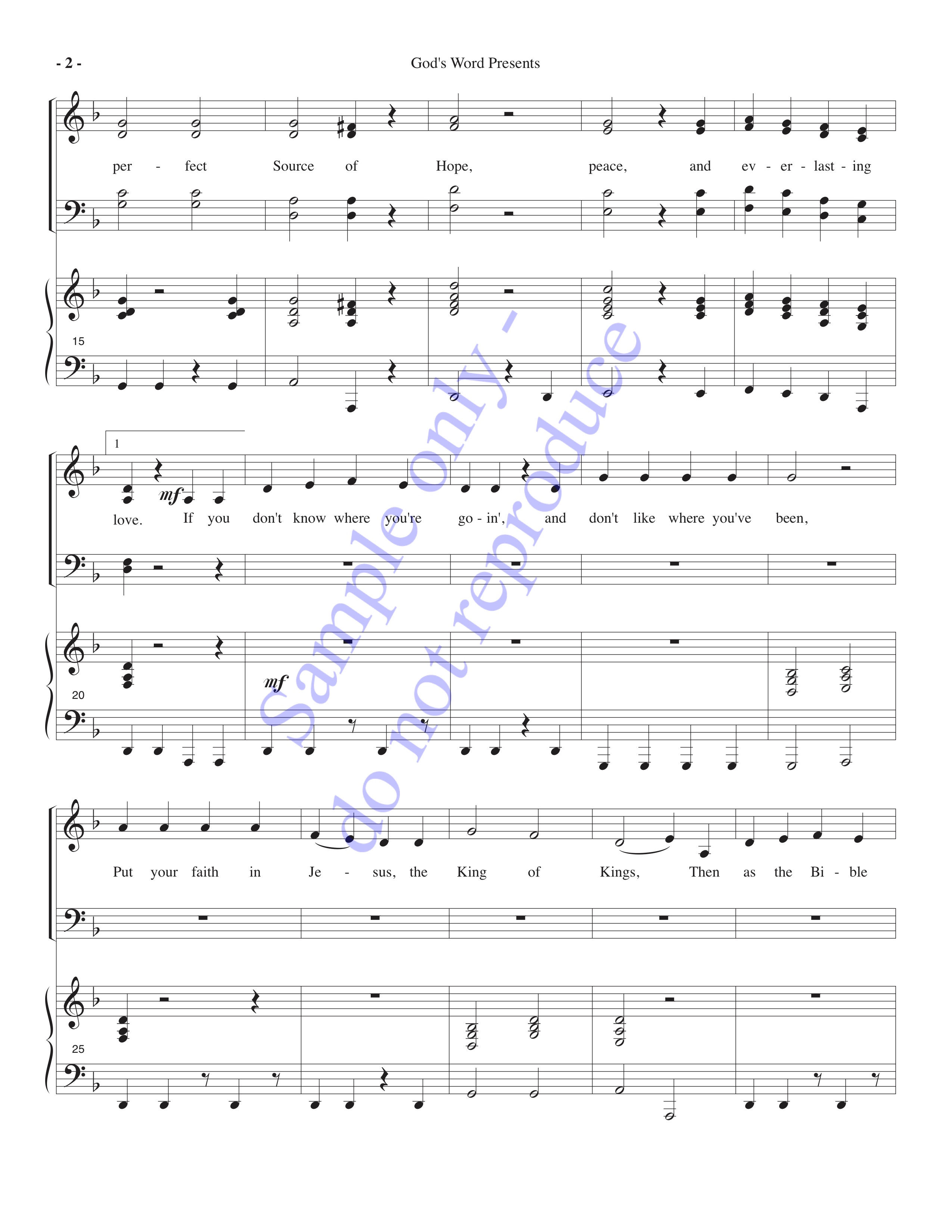

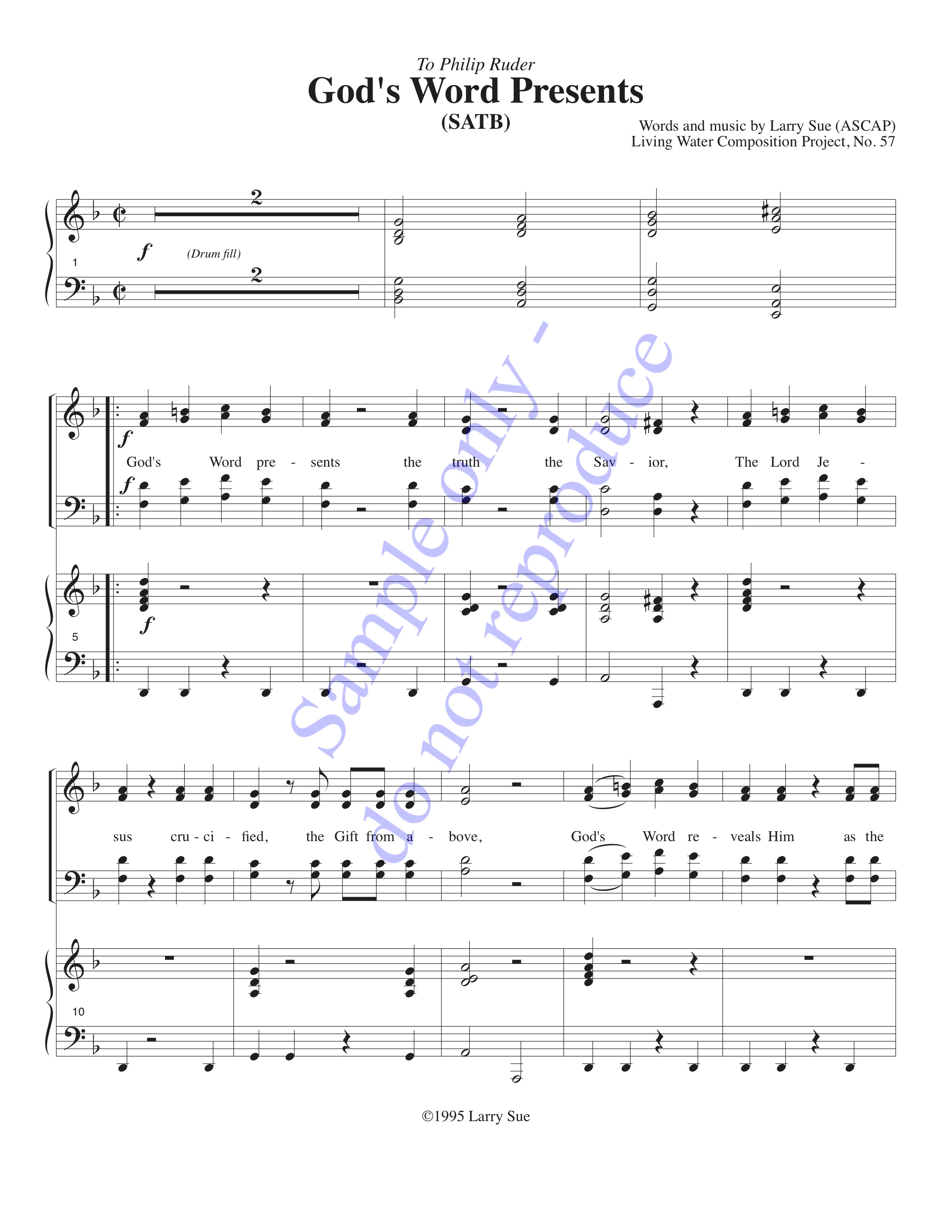

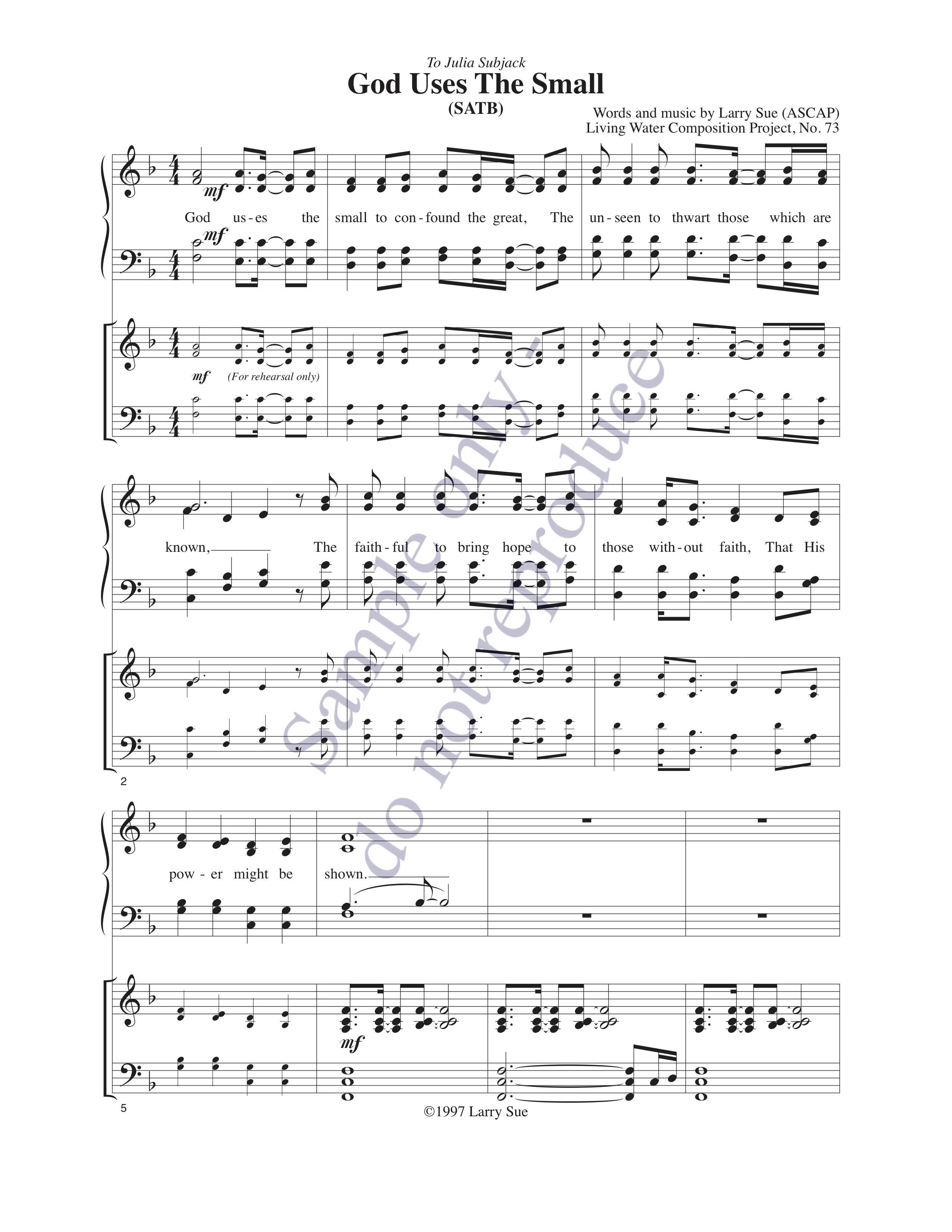

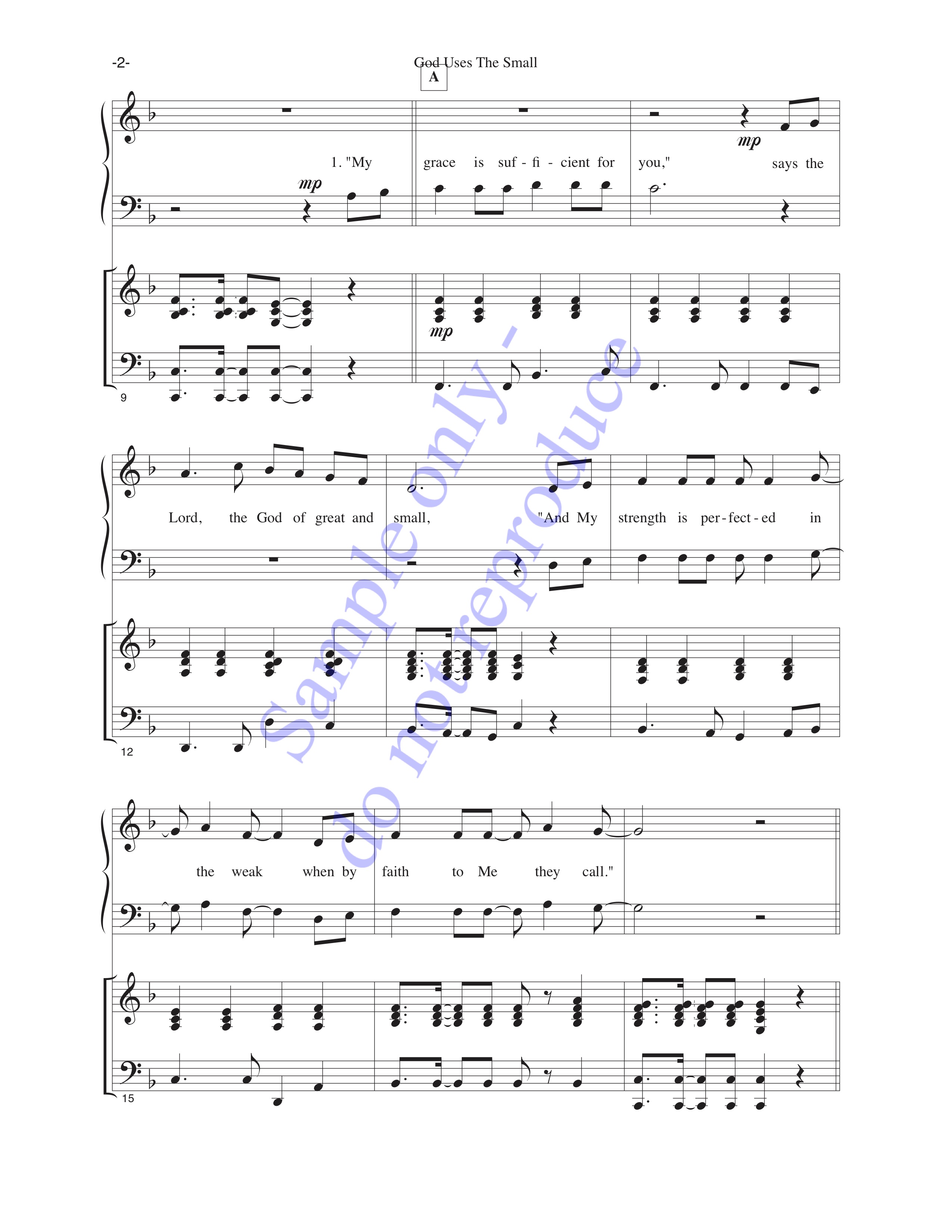

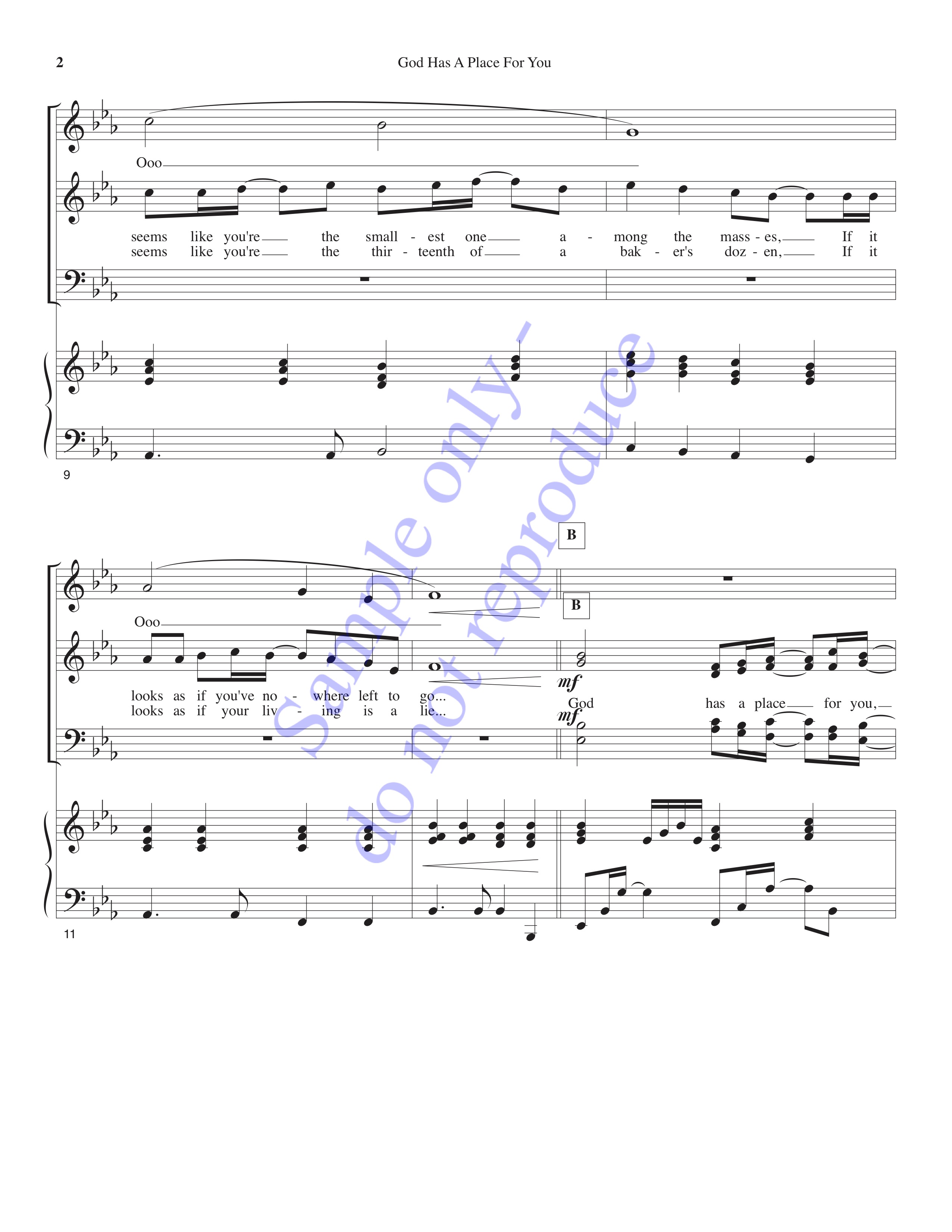

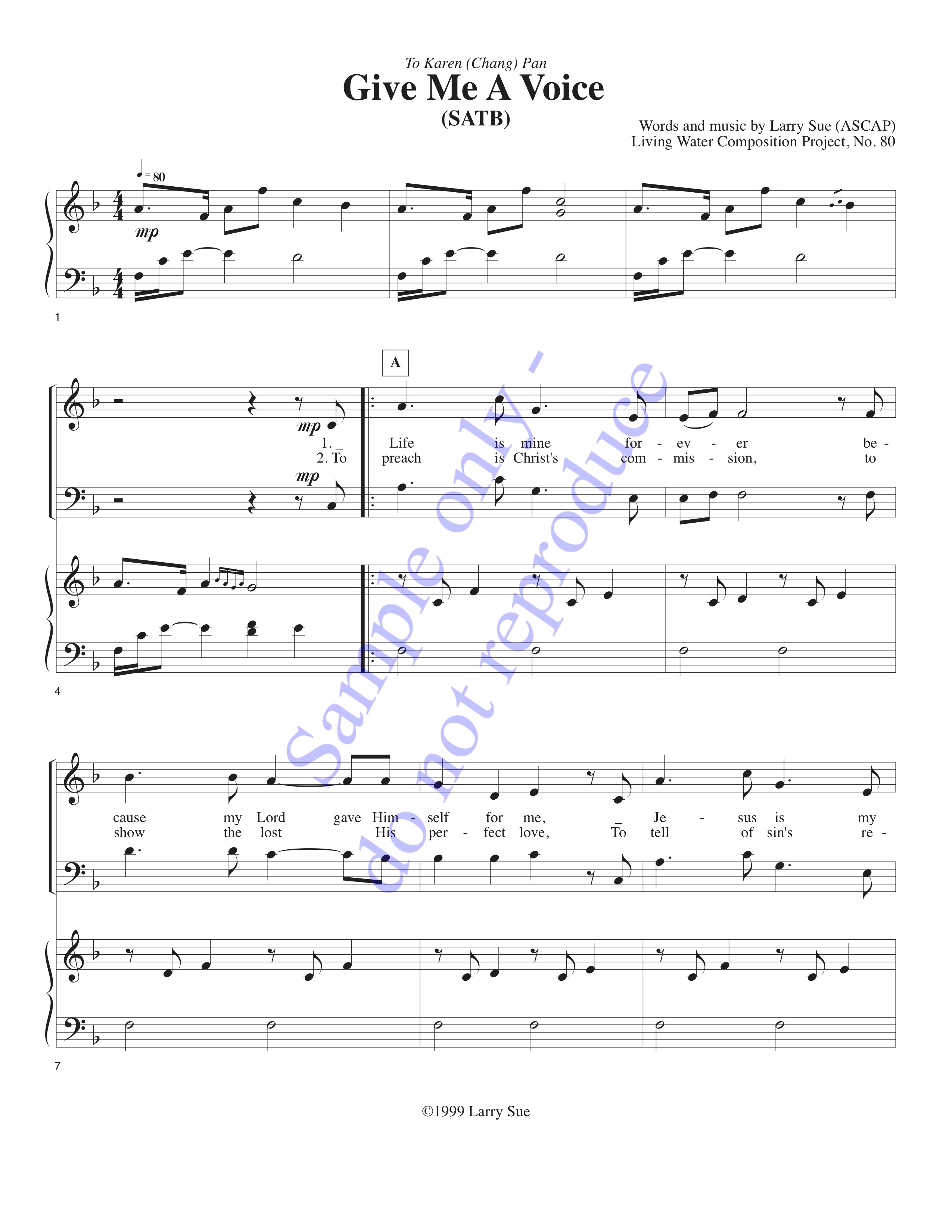

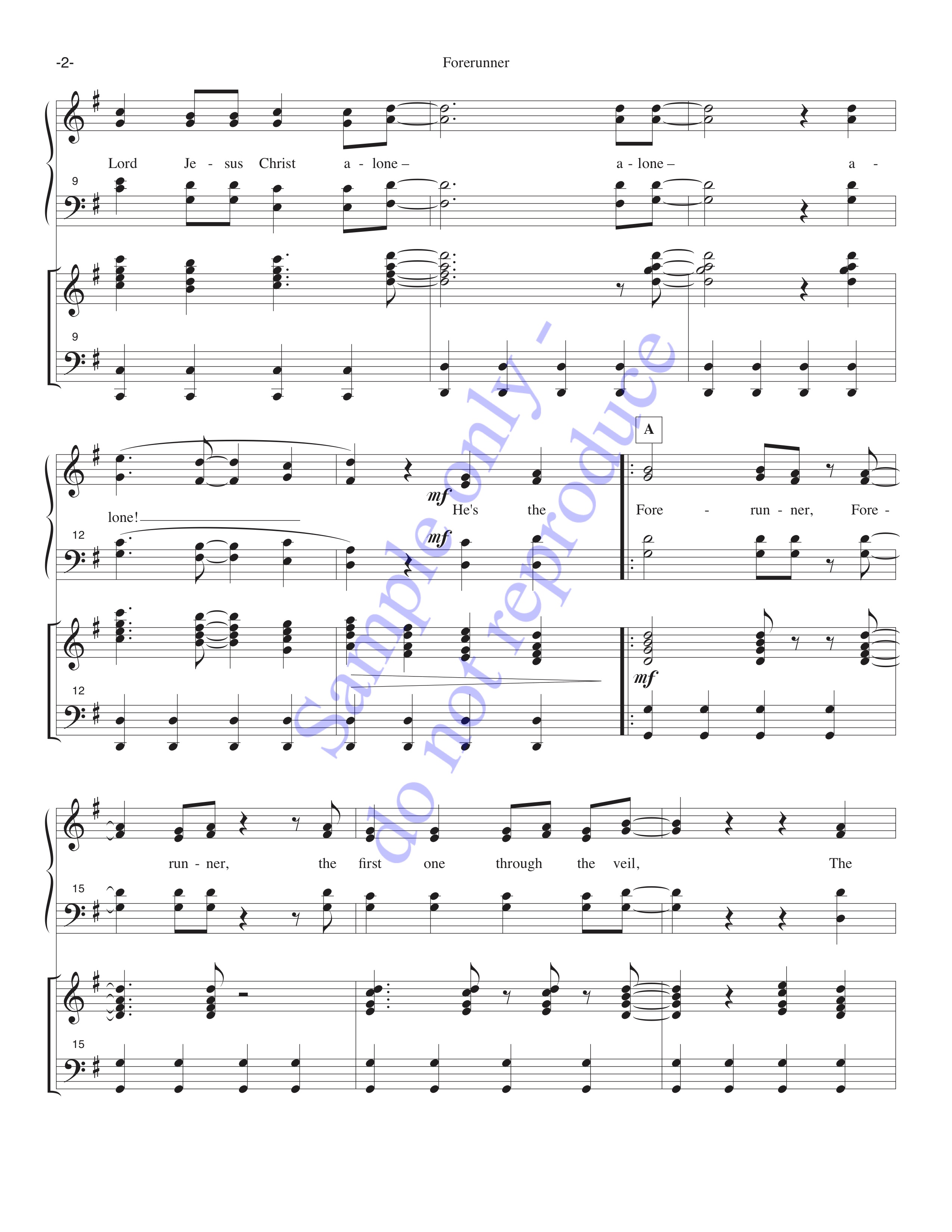

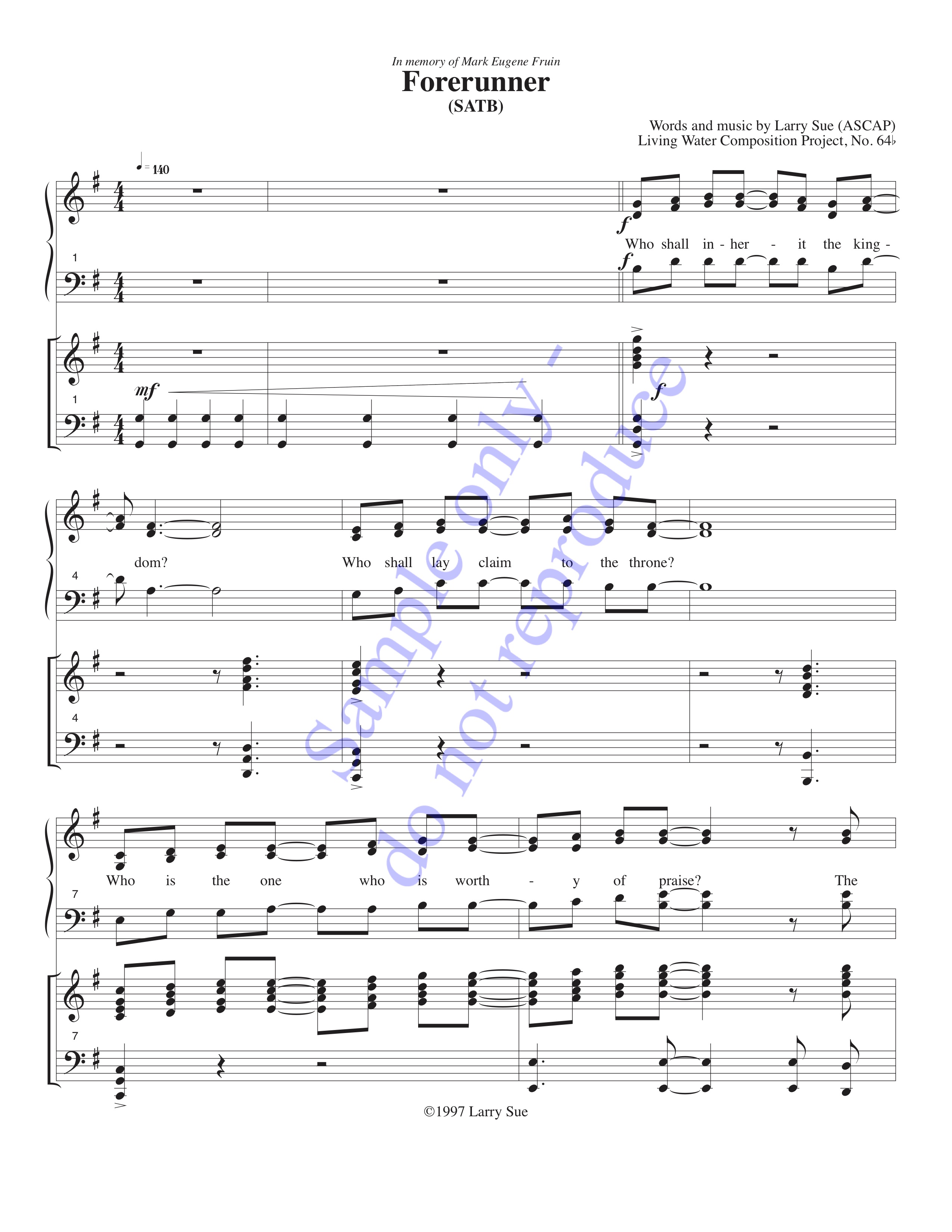

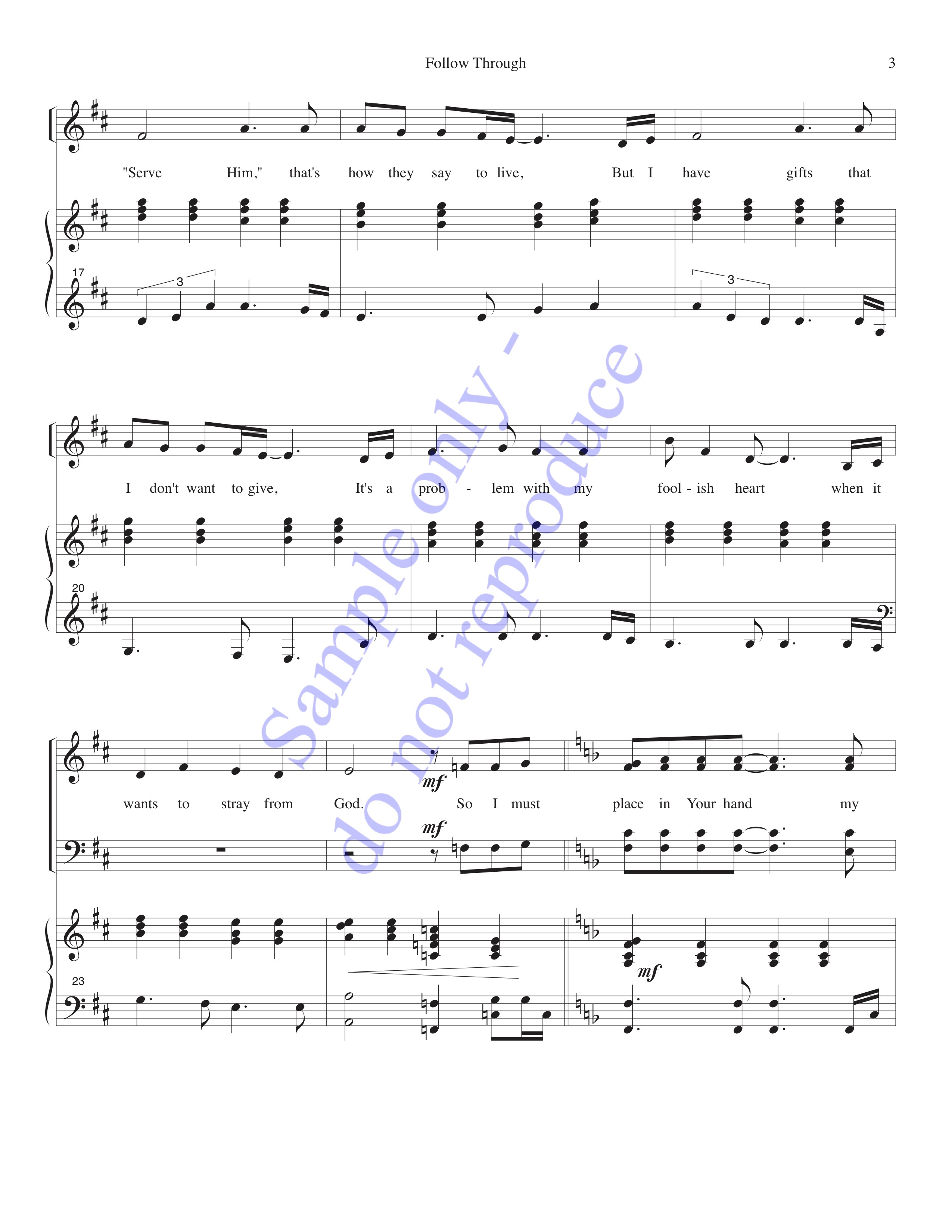

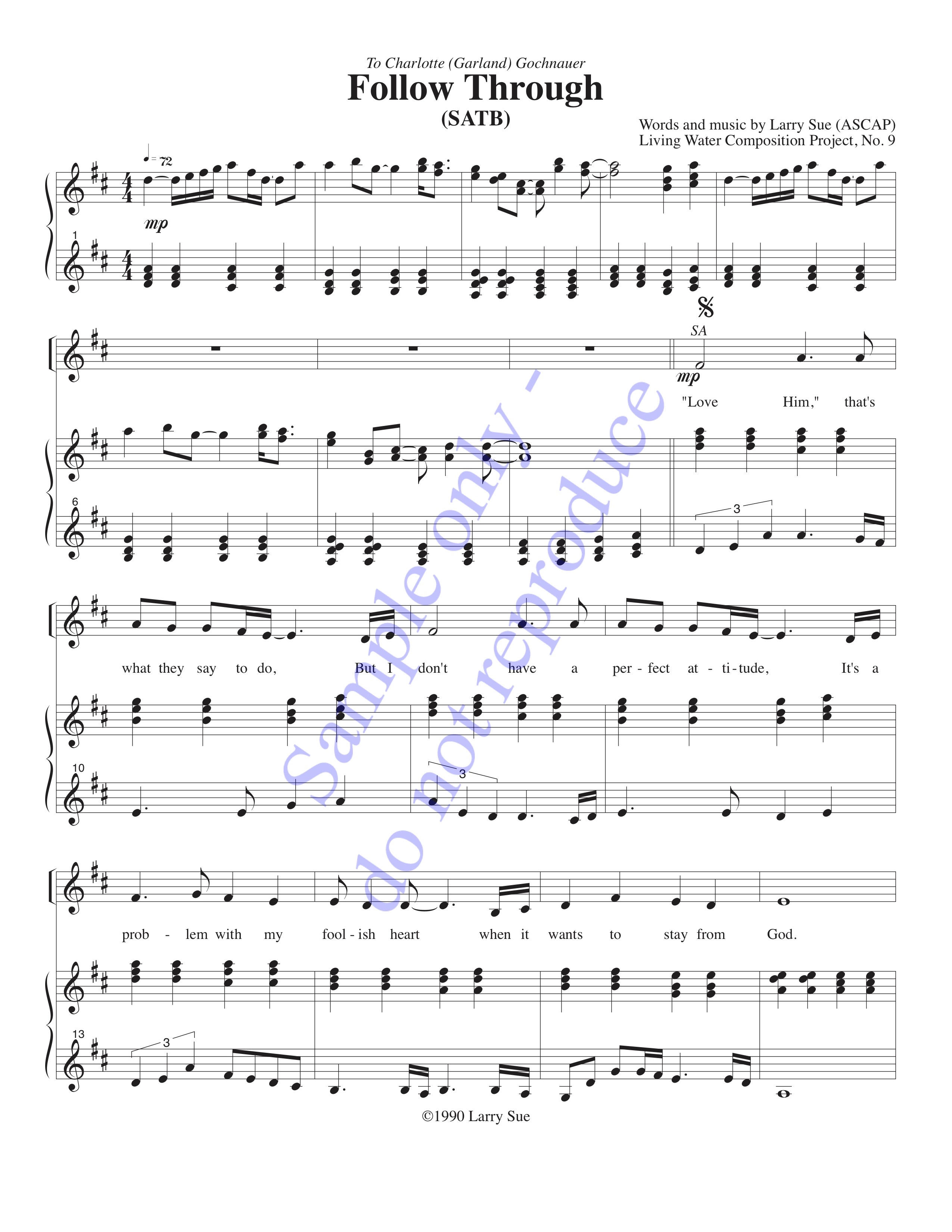

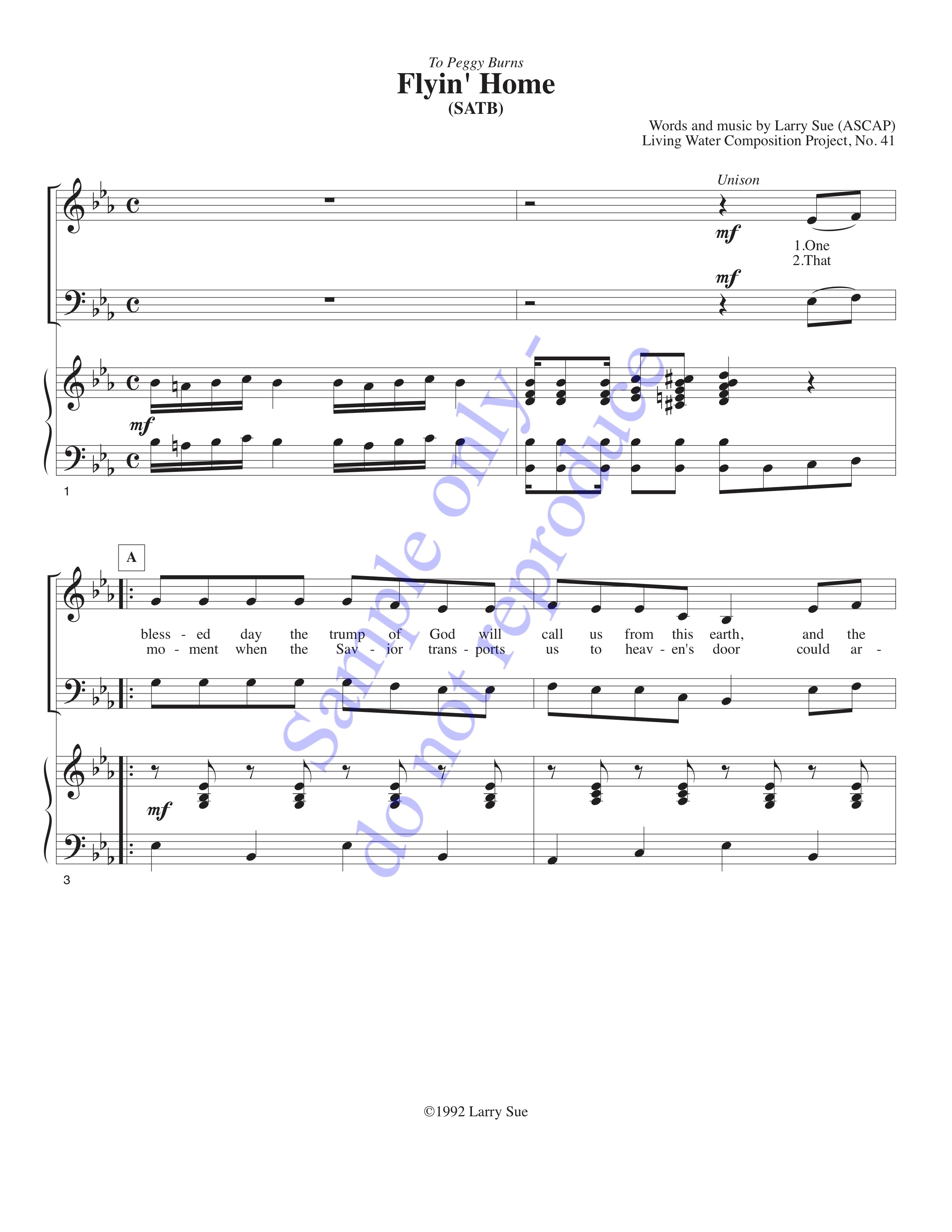

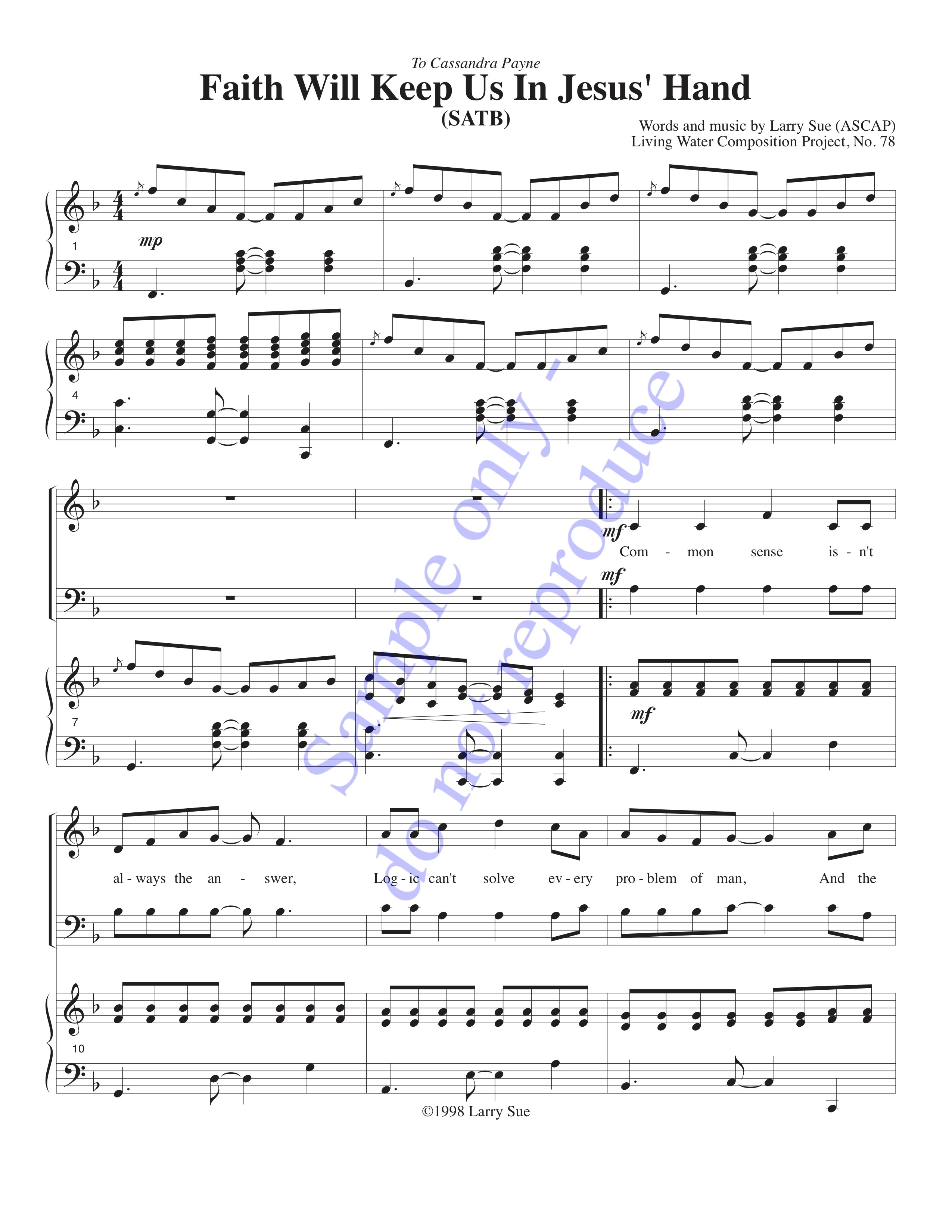

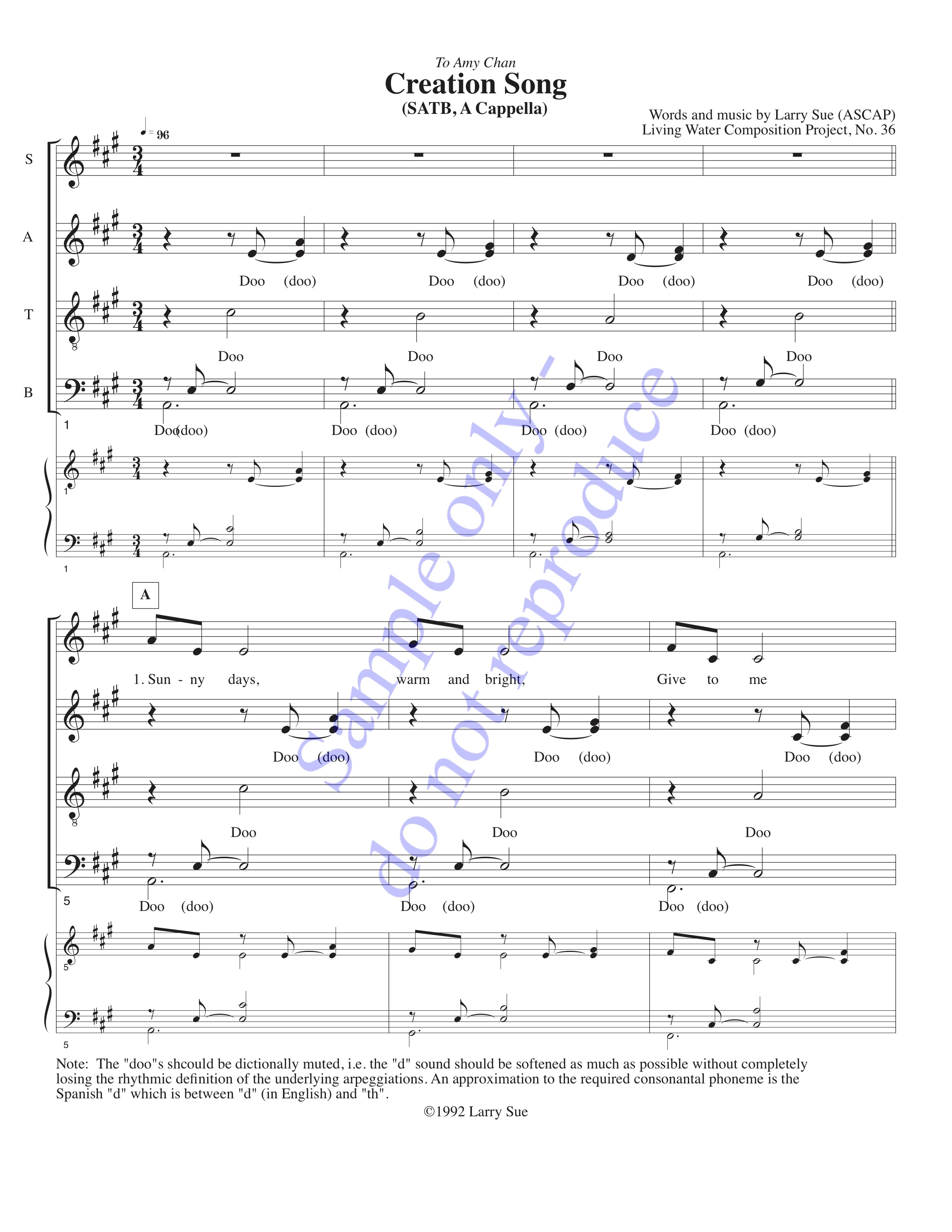

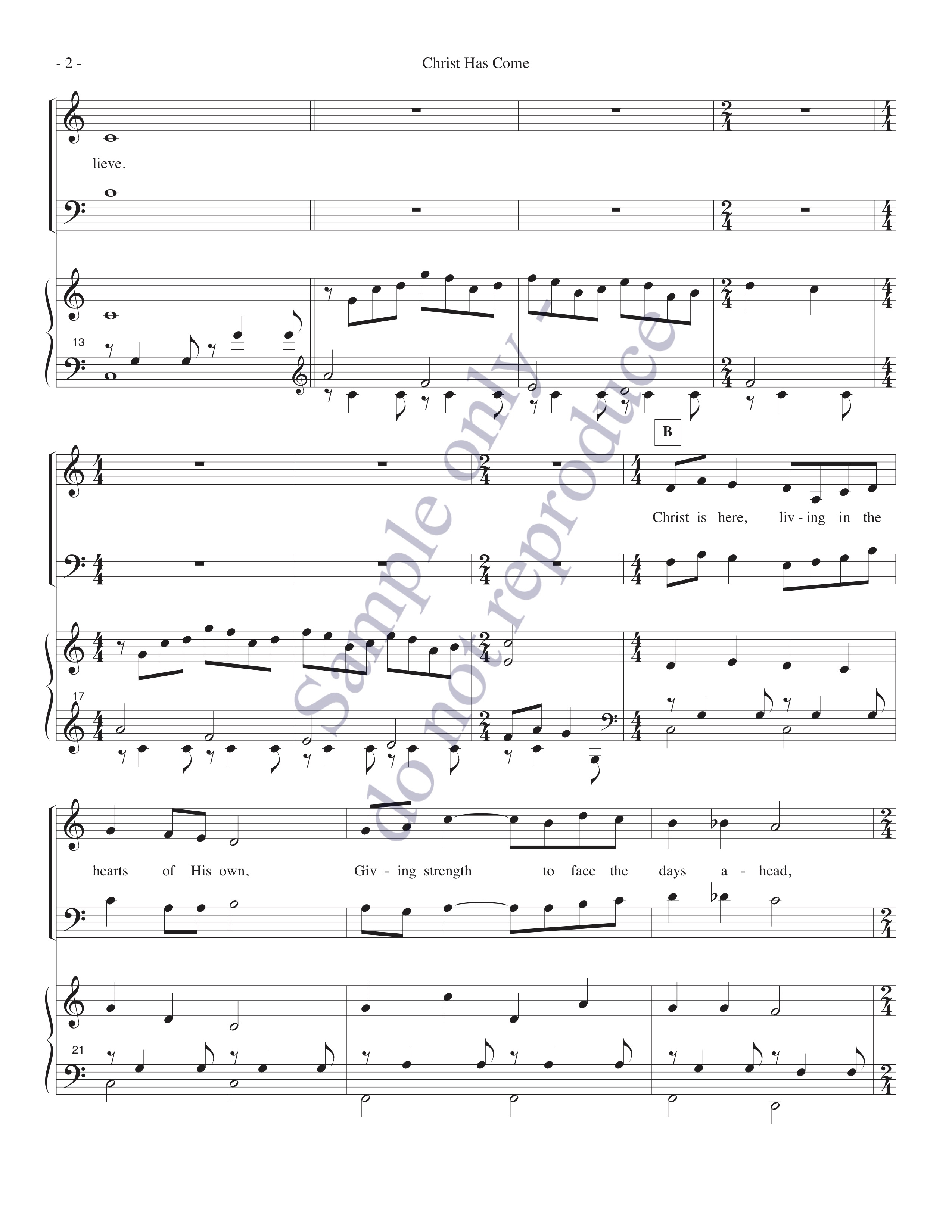

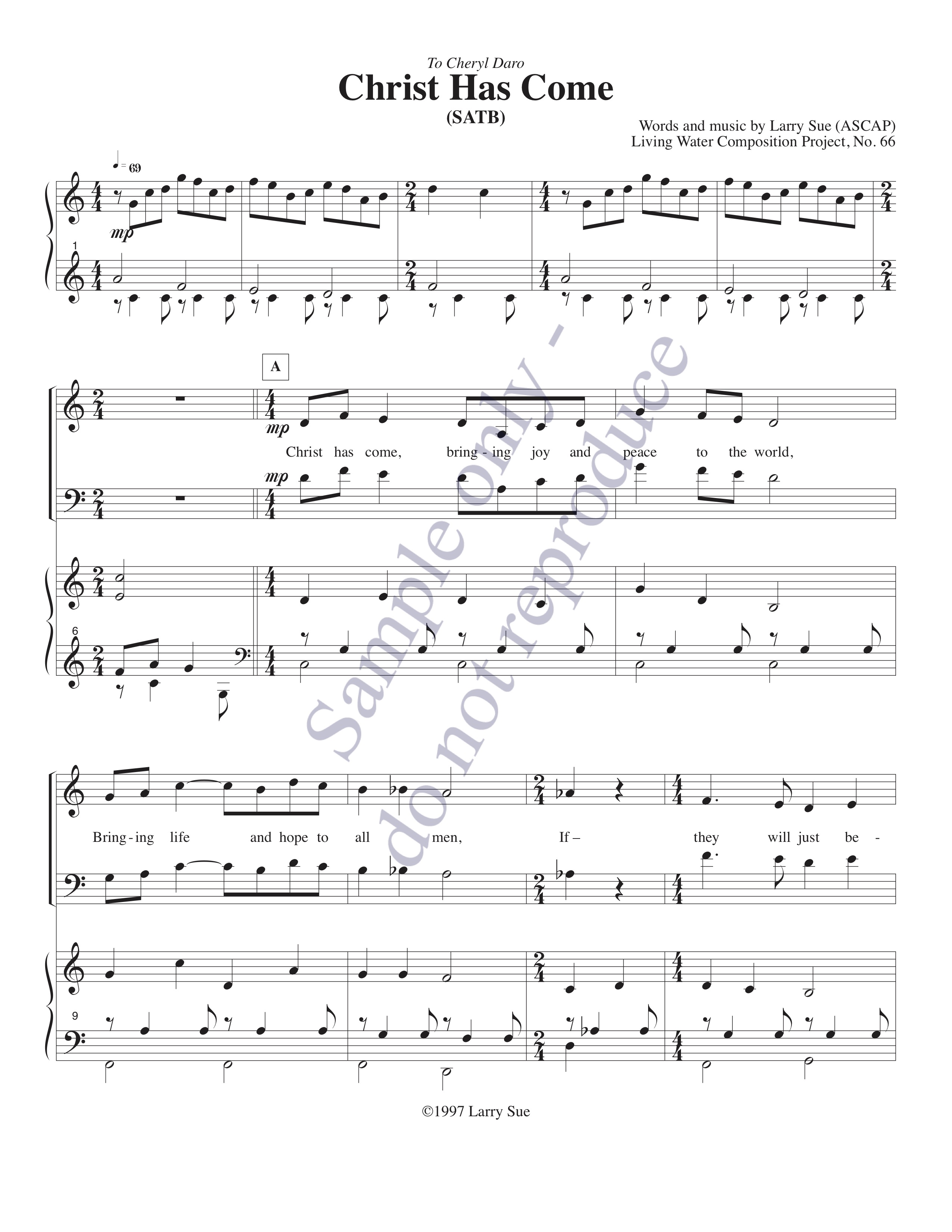

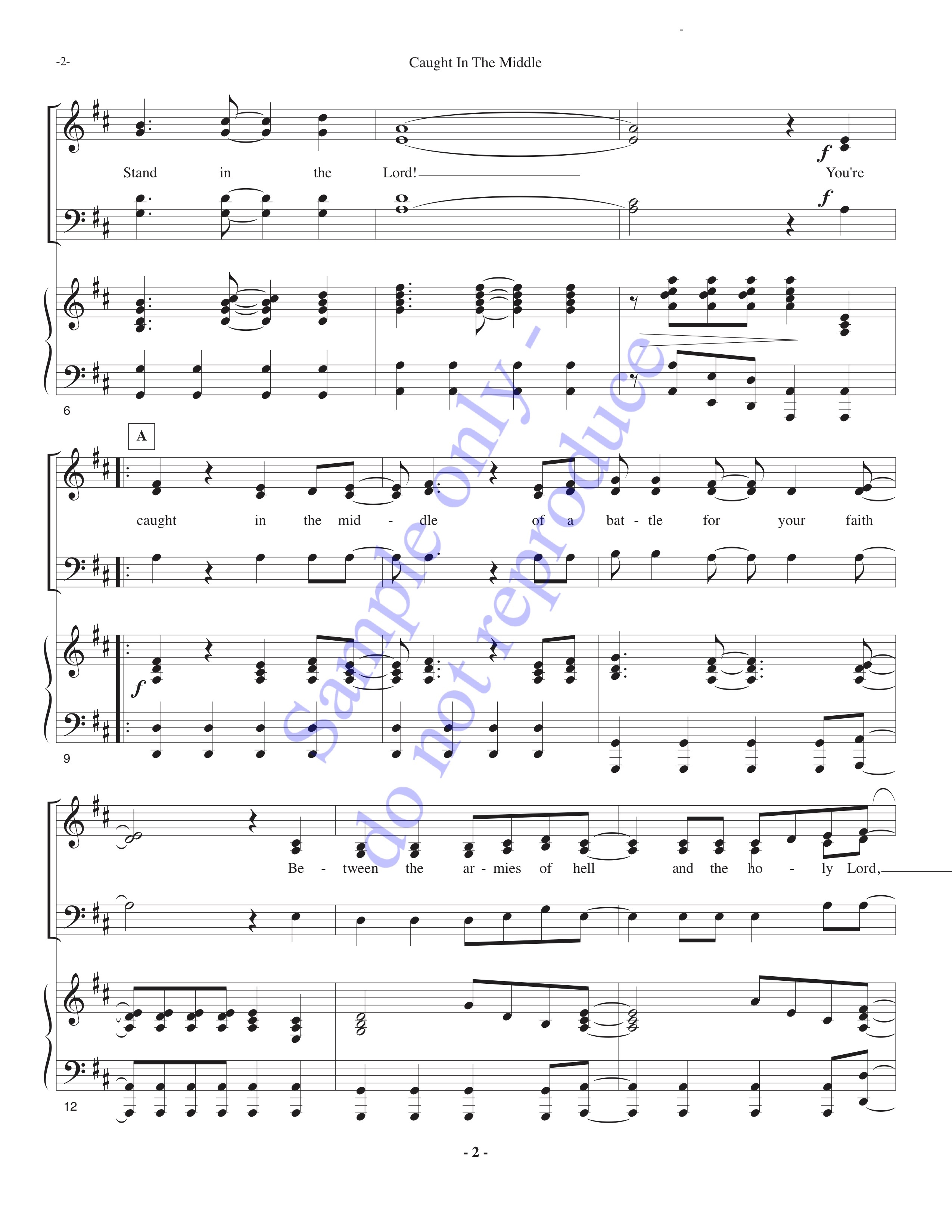

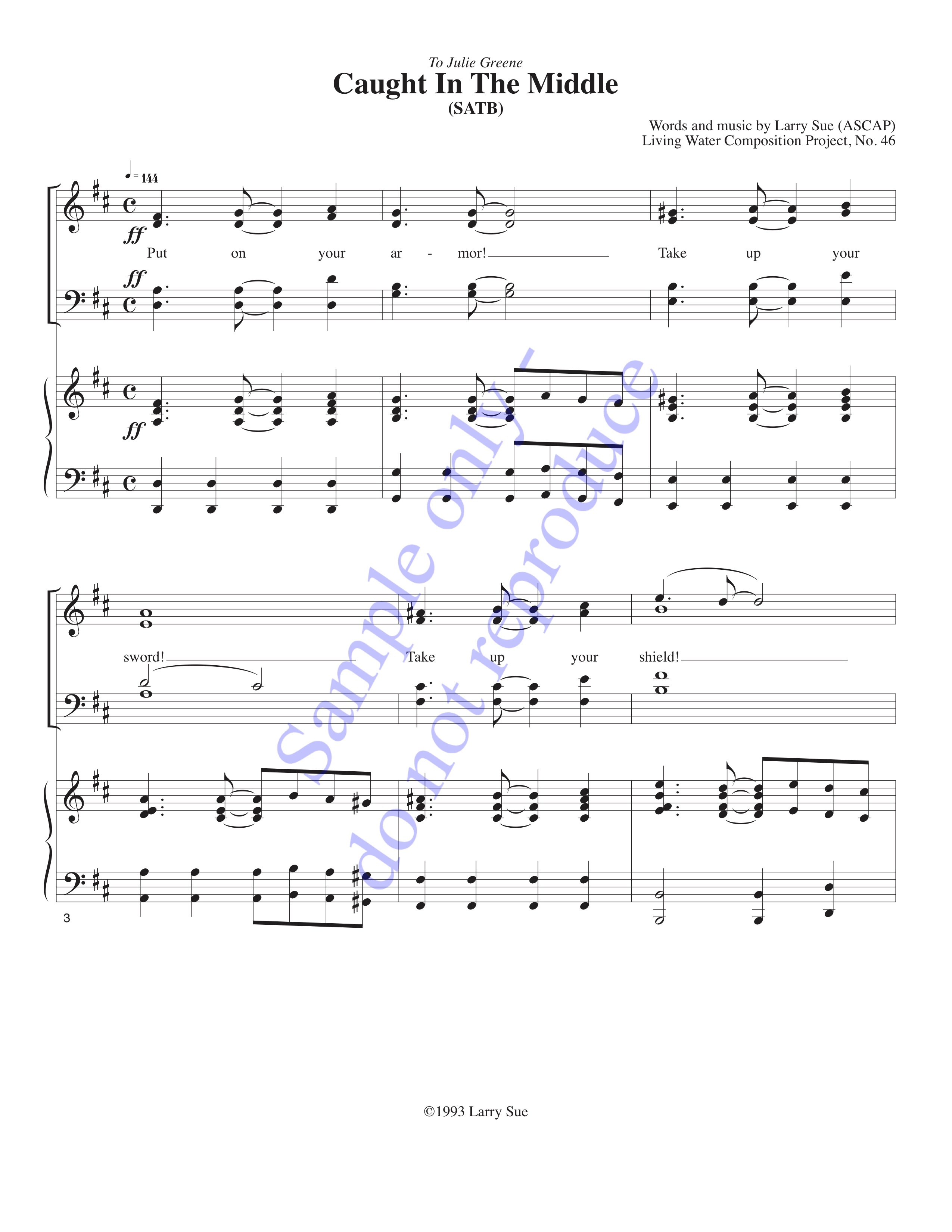

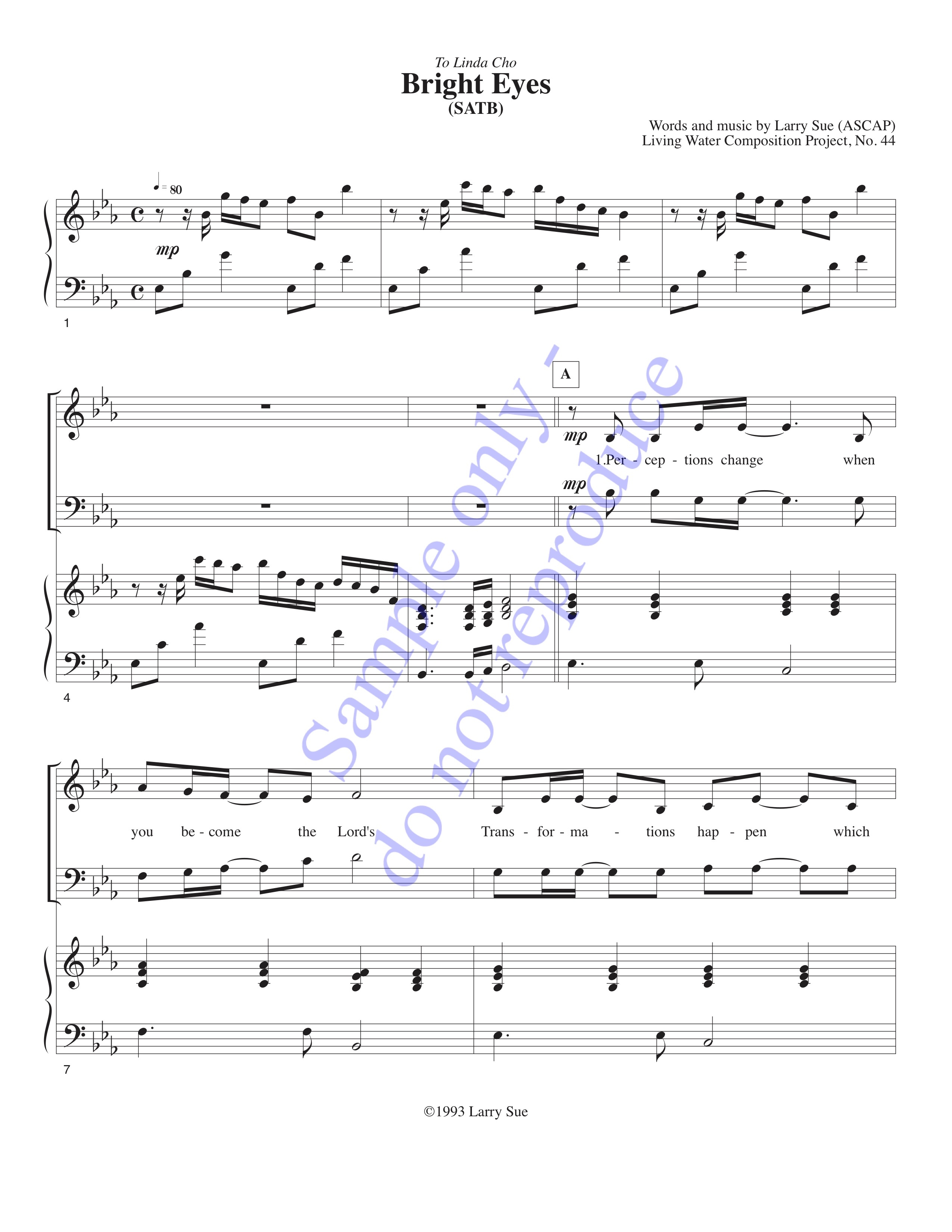

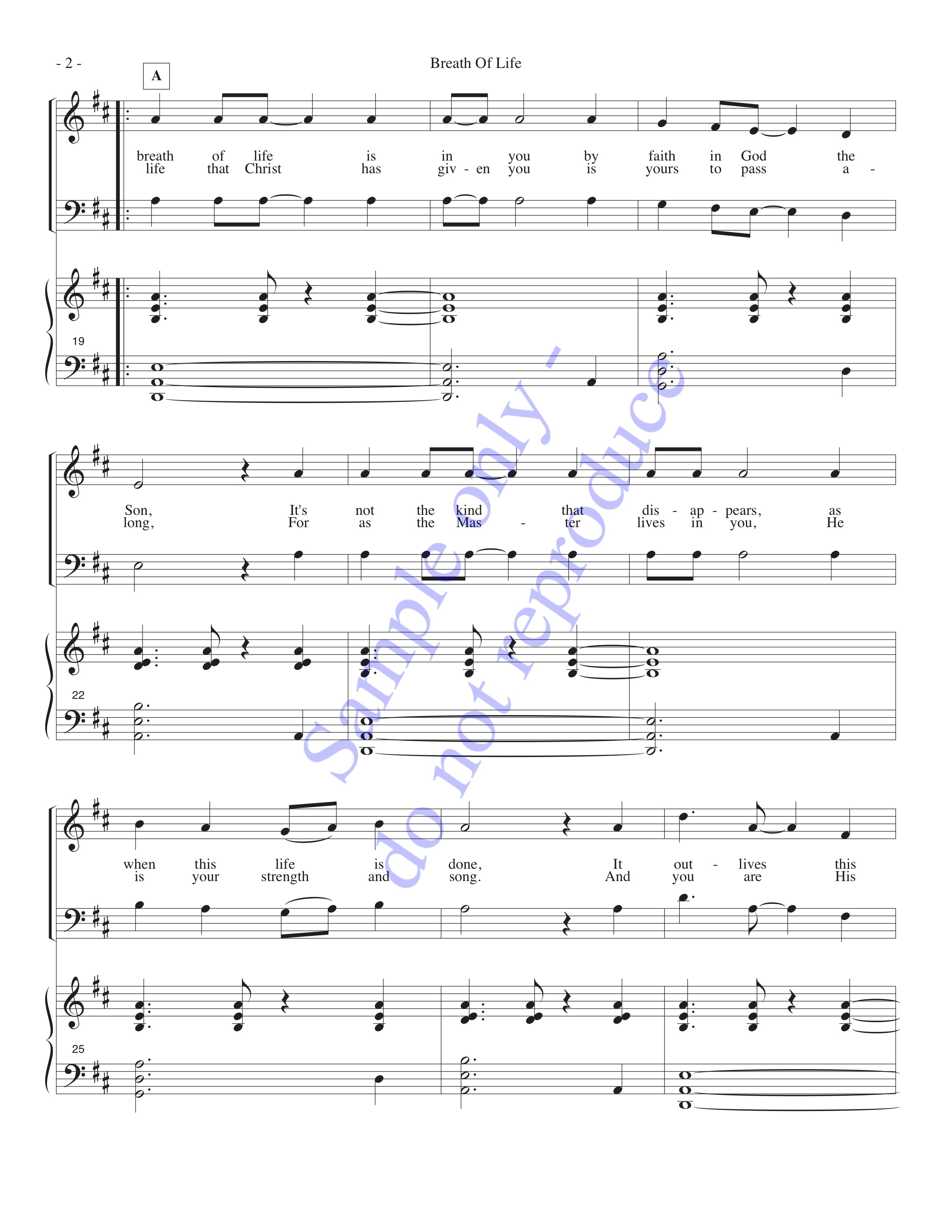

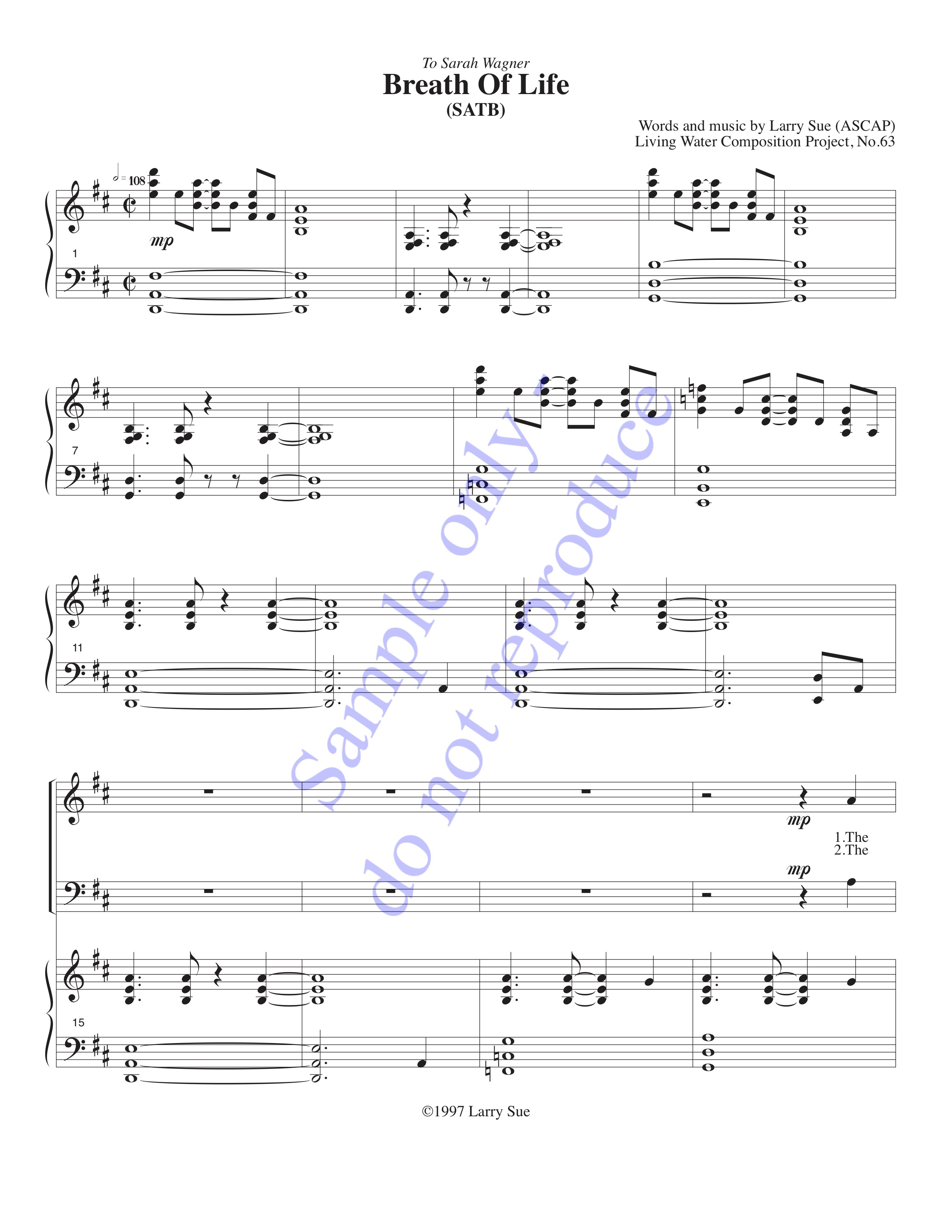

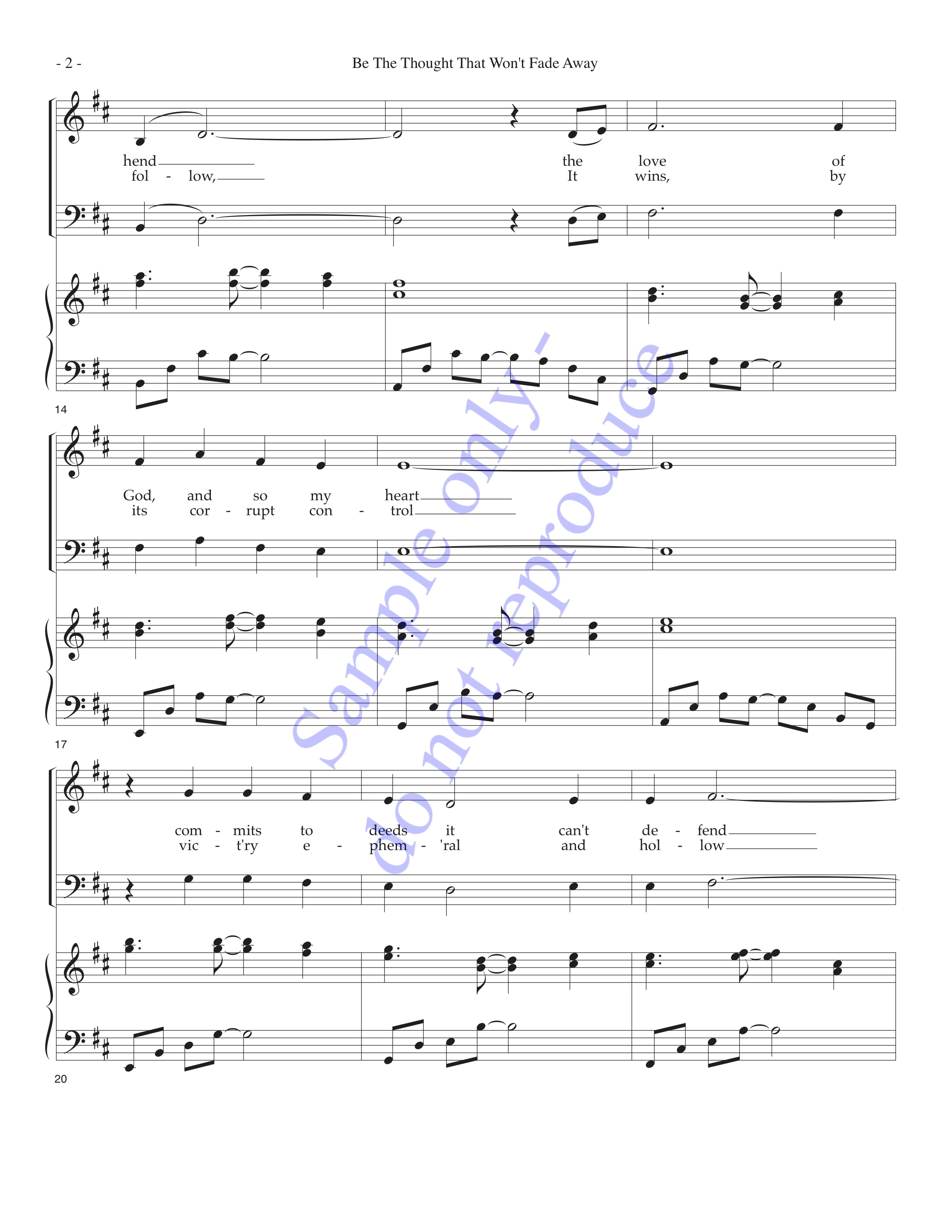

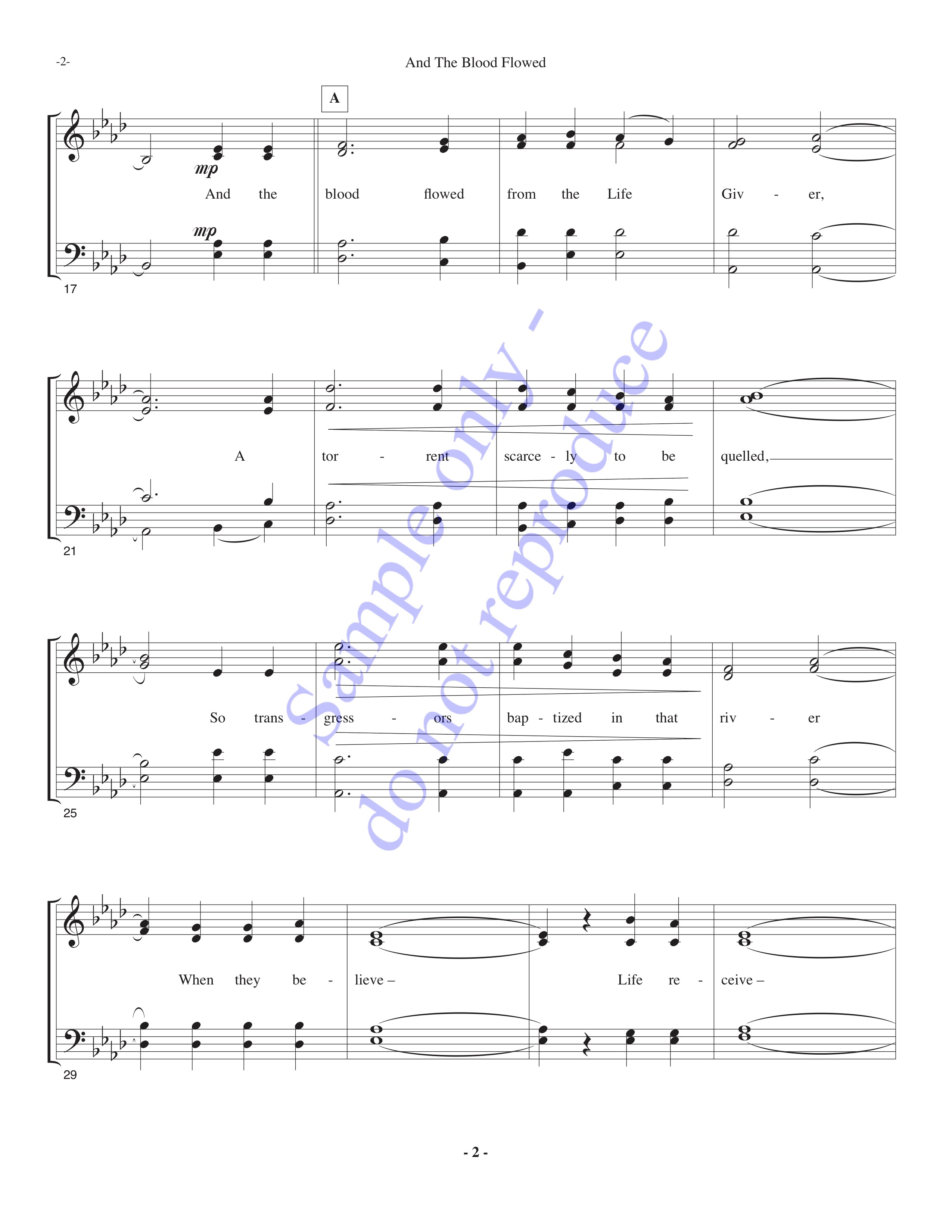

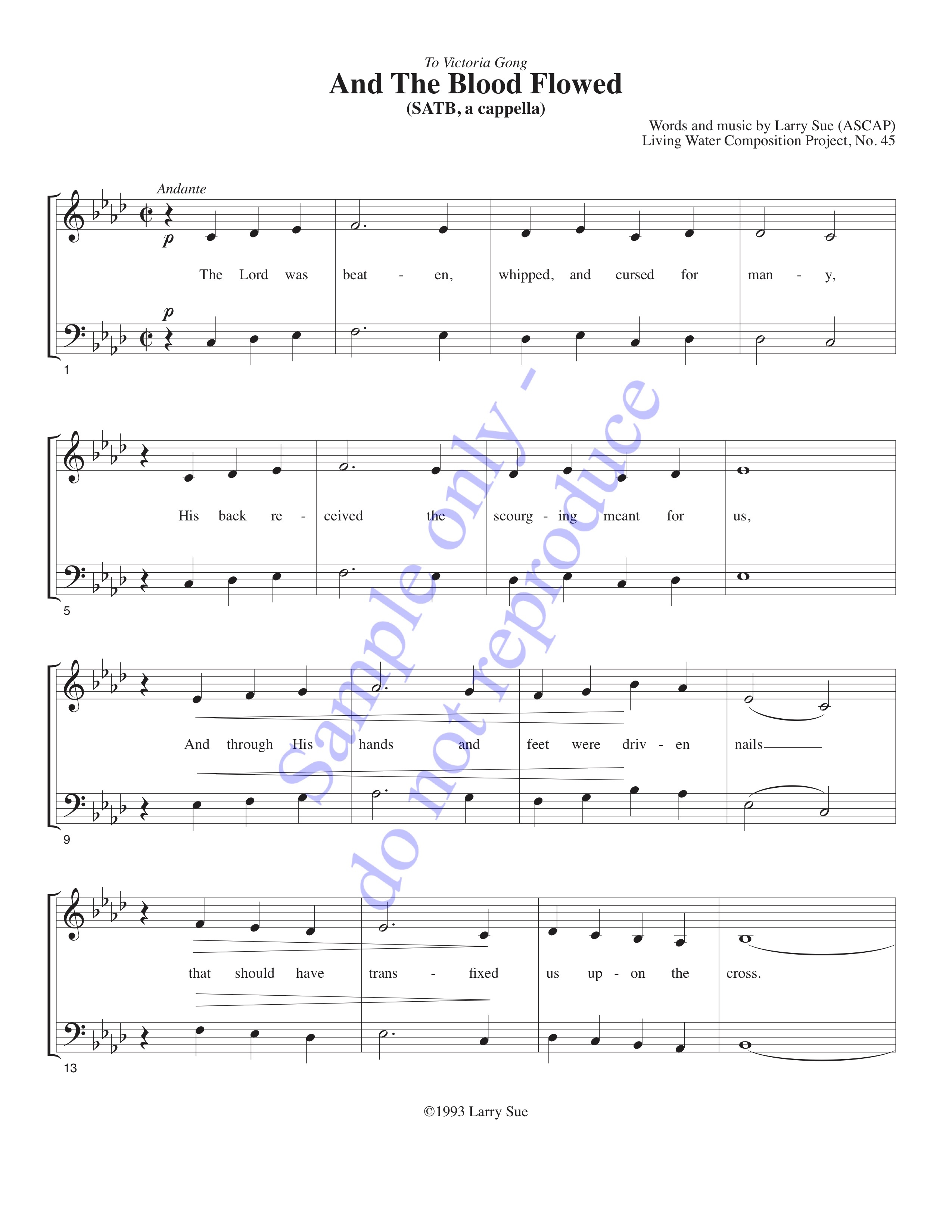

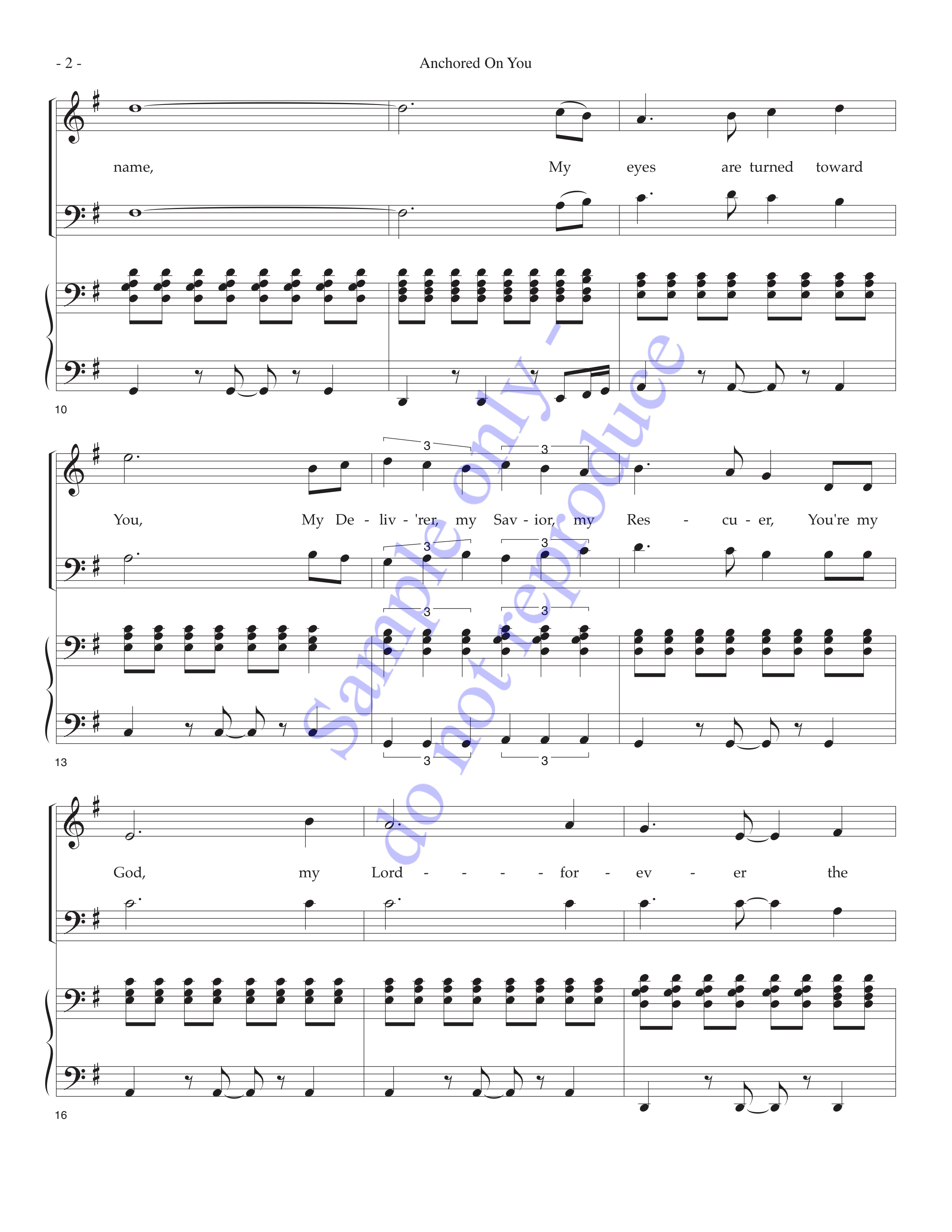

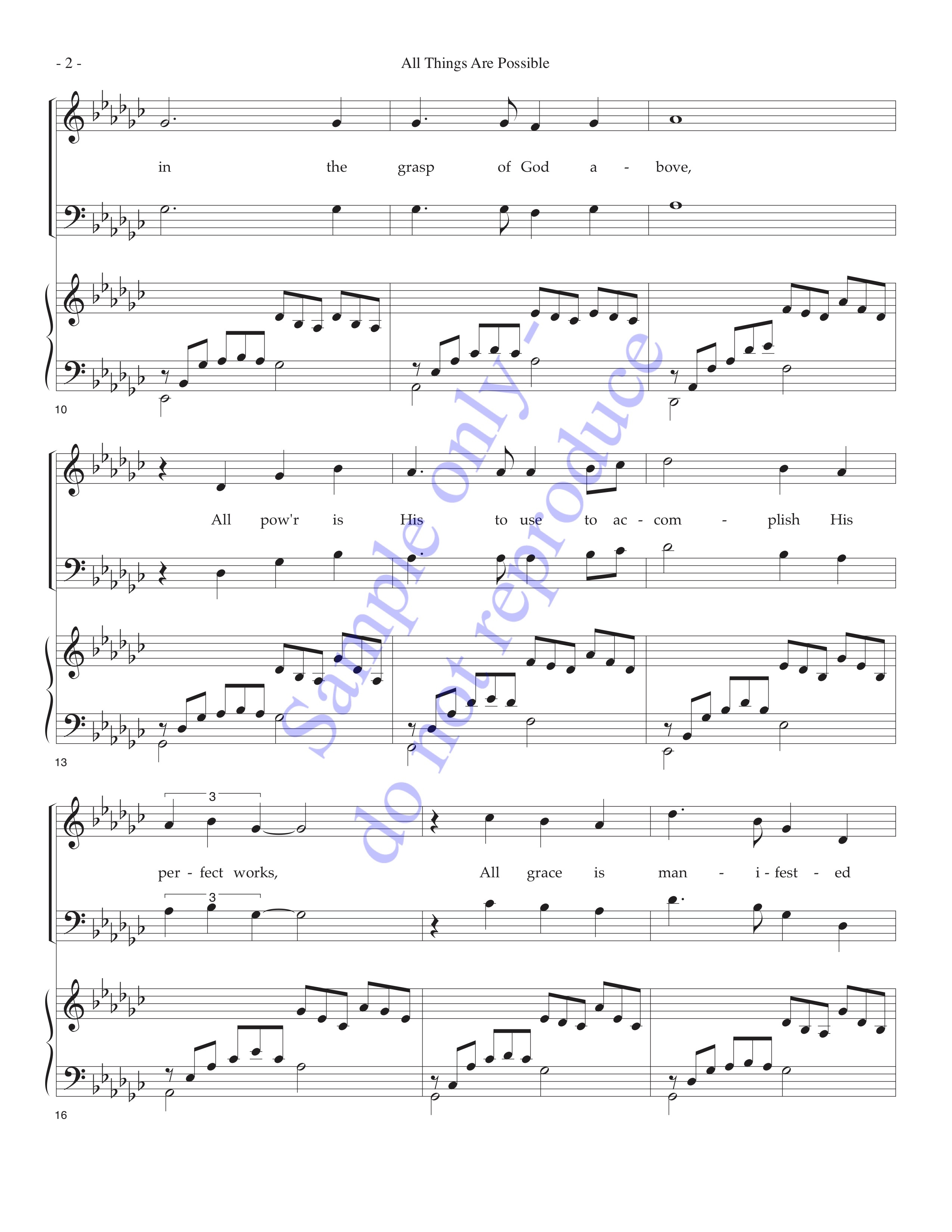

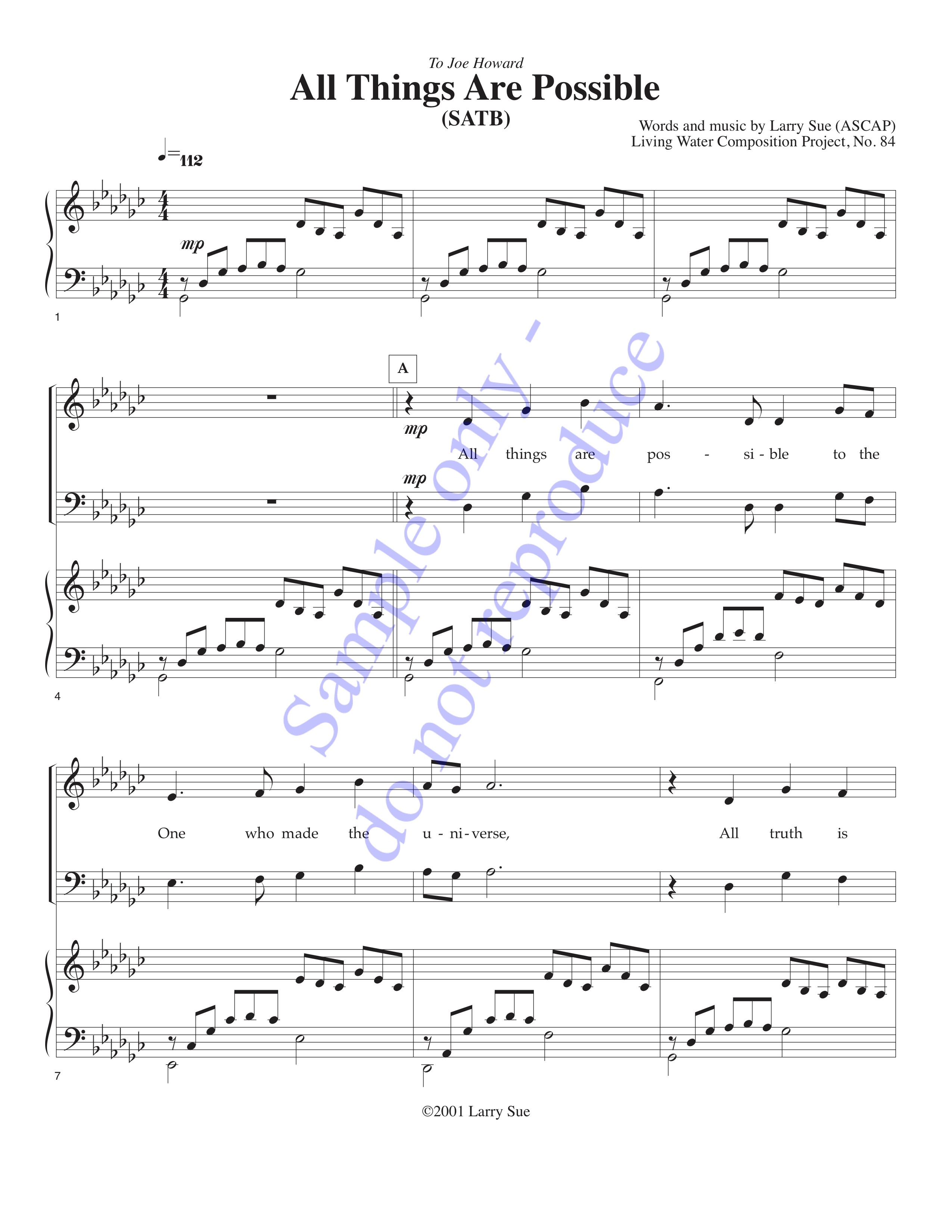

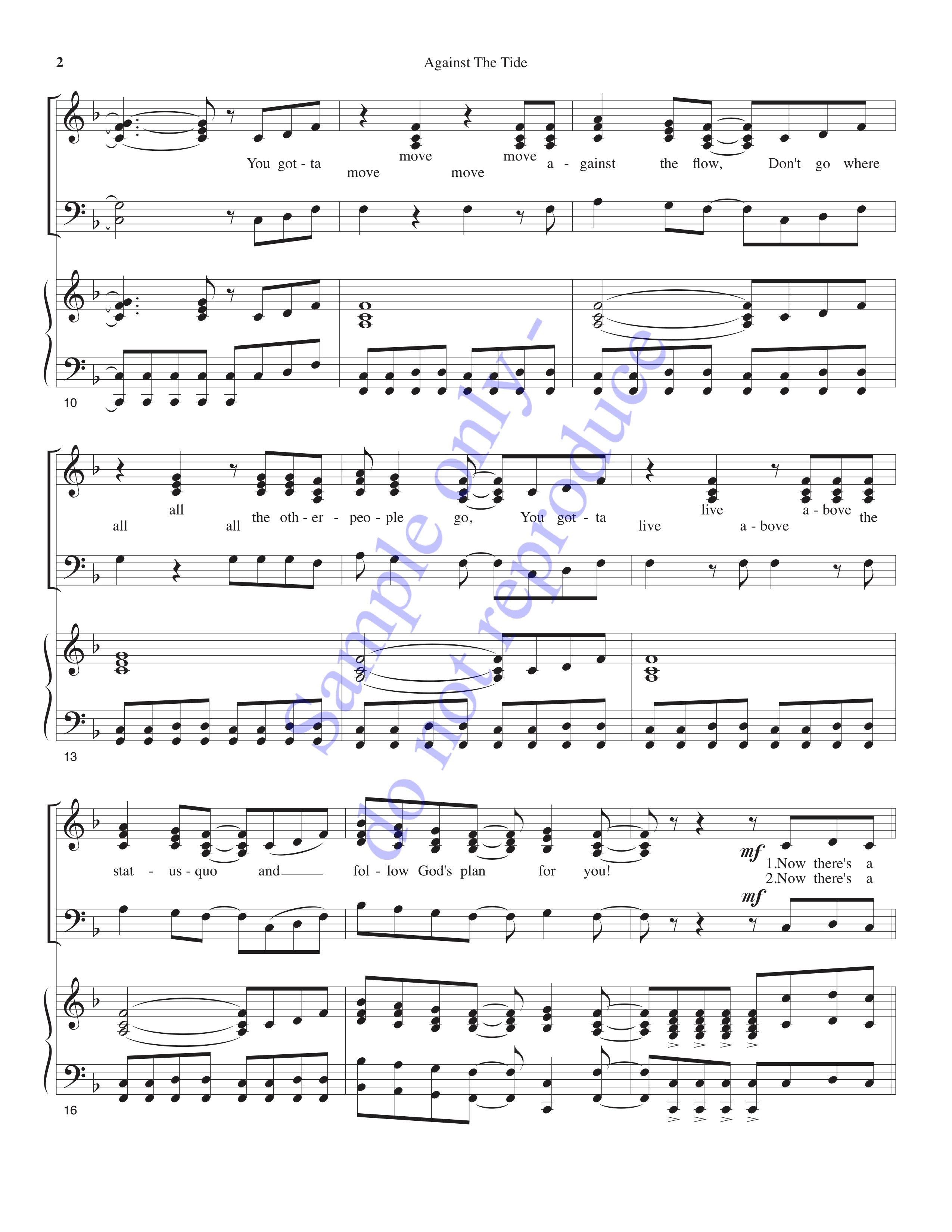

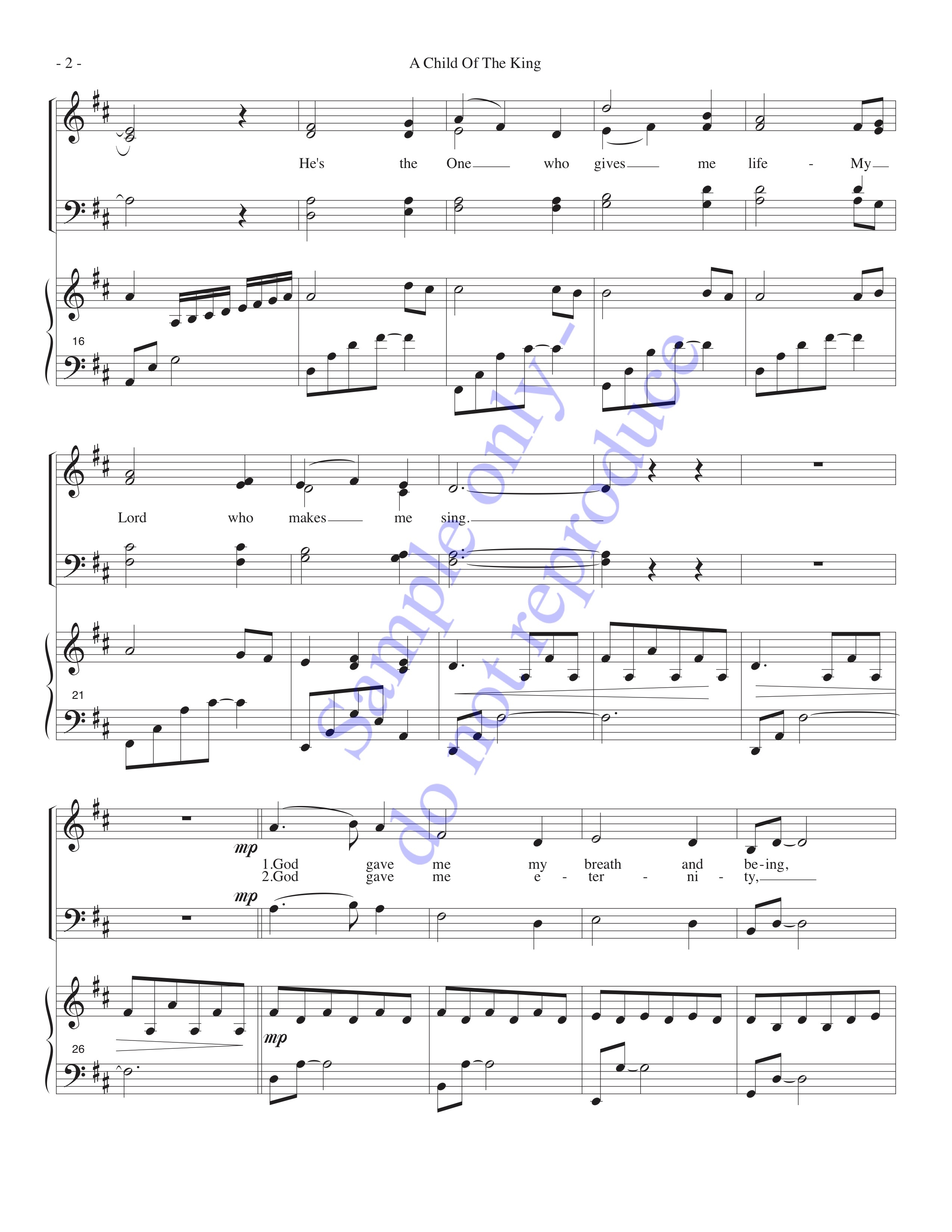

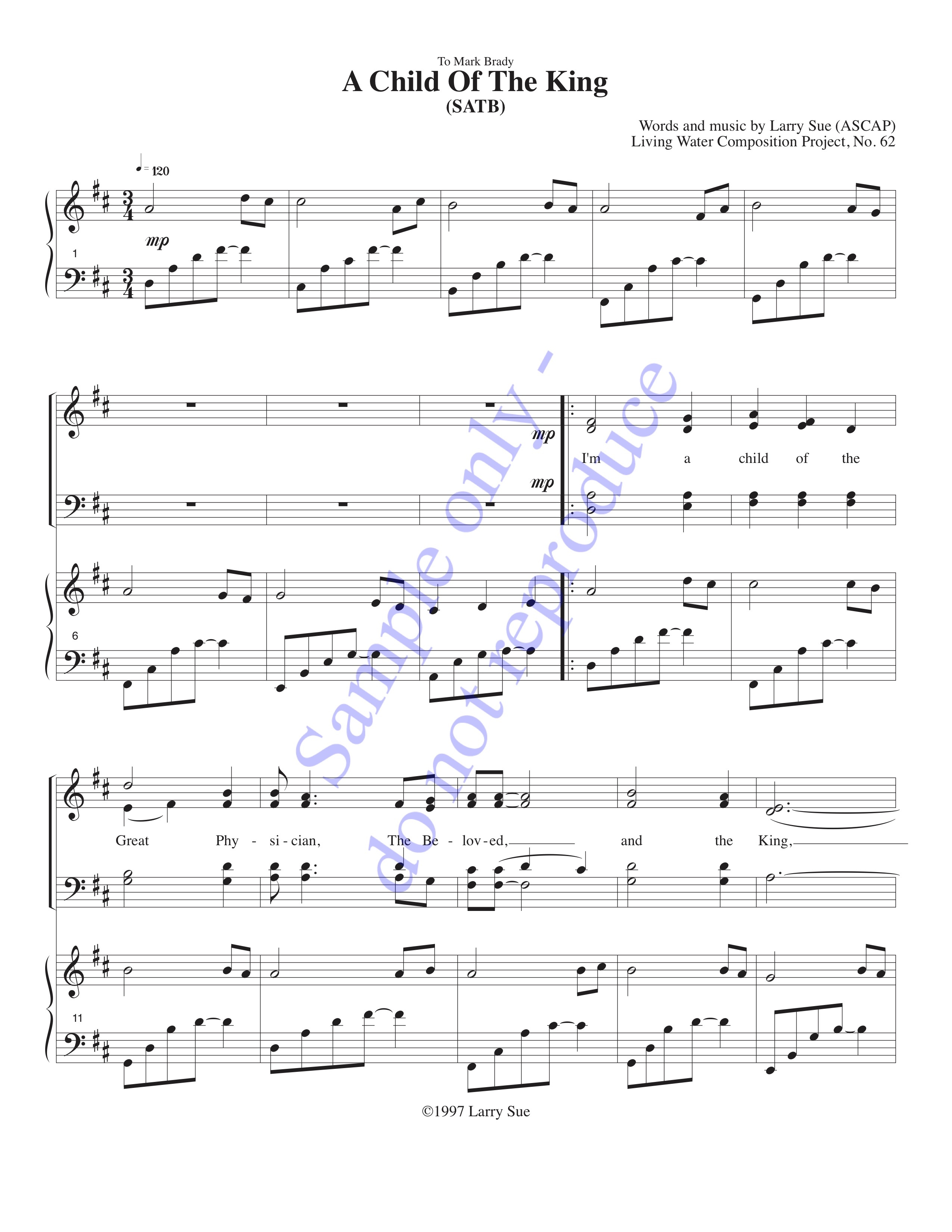

I also write songs dedicated to the members of Living Water (you’ll find more information on this on the pages about the Living Water Composition Project). While I realize that this isn’t something every choir director can do, it’s another way to tell them I love them (and, like the birthday presents, it’s a “forever project”).

Guiding Principle VII: Use nonverbal communication.

There’s a measure of practicality involved in using nonverbal communication during rehearsal: You can’t use anything else during performance! The saying about how we practice determining how we perform holds an awful lot of water: If we train our choirs to look for one set of cues when we practice, how are they going to adapt to a different set of cues when we’re singing in worship? Or: what’s going to happen when the cues we use during rehearsal are gone?

My friend Dennis Krause likes to teach in terms of “empathic response.” The operating premise is that how you look and act as the director subconsciously affects how your choir sings:

If you look confident, they will sing with confidence.

If you look thoughtful, they’ll sing thoughtfully.

If you look uncertain or tentative, they’ll sing hesitantly.

And so on… what you do will always be mirrored in your choir. If you don’t believe me, just try raising your shoulders half an inch while your choir’s singing (don’t tell them you’re going to do this) – I guarantee that the ones who are watching will start to sound slightly tense. Raise the beat pattern about three inches, and the general timbre will lighten; lower it three inches, and the timbre will become darker/deeper. By the way, once you’ve done this to your own satisfaction, stop and tell your choir how well they follow you!

Over the years, I’ve developed a fairly large set of nonverbal signs which I use regularly as I direct both in rehearsal and performance. The importance of having these tools is that since they don’t affect the choir’s sound, they can be used at any time. This set of signals continues to grow with time because I can always find new things I need to express.

Now, I admit that you might have your own set of signals. That’s perfectly fine! It’s much more important for you to find a system that works for you than to use my system. The key is to make certain that the signals are unambiguous and self-consistent. Anyway, here are mine; feel free to use them if they appeal to you!

“Eyes”: Tells the choir I want them to watch me. Is indicated by pointing to my eye with one finger. I realize that this is self-defeating in that the people who aren’t watching won’t see this, but perhaps you can get around this by having the people who are watching give a quick elbow to the ribs to the others… Remember, eye contact is essential to communication!

“Words”: Says that I want more intense (clearer) diction. Is indicated by a “yakkity-yak” signal (sometimes called a “clam yell”).

Cresc./dim.: Indicates dynamic change and how fast it’s to happen. There are a number of ways to indicate this, any of which you can use at your discretion, and none of which are entirely satisfactory. Using two hands (separating or coming together) is effective at indicating relative volume, but tends to crush the tone on diminuendi (empathic response). Palm-up reminds the singers of breath support, but causes a tightness on crescendi because the shoulder tends to rise (empathic response!). Palm-down avoids the problems of the other two methods, but may not be as expressive as you’d like on occasion. My advice: learn all of these, find which one works best in each situation, and use them as need requires.

Cutoff: First advice: DO NOT make a circle before indicating a cutoff. Although it tells the choir that the cut is coming, it makes it a lot harder to see when it actually happens! Here are three alternatives:

“Hot stove touch”: Pretend you’re reaching out to a hot stove with your hand, and at the instant at which you want to indicate the cutoff, pull back as if you’ve touched it. This is a wonderfully precise way to indicate a cutoff which works best at the end of a phrase.

Finger touch: Hold your hand so that the choir can see your thumb and fingertips, then touch a thumb and finger together to indicate the cutoff. This method is easier to use than the “hot stove touch” because it doesn’t require as much arm motion. By the way, touching different fingers with your thumb changes the speed of this action, and therefore can be used to soften or harden the cutoff itself.

Wrist rotation plus finger touch: If you turn your hand sideways a bit, you can rotate your write in the direction your fingers are going on a finger touch and so make the cutoff even sharper.

“H”: The “H” signal came into being to remind people to put an (H) on each note in a melisma. It’s not ASL, but it works: Just make a Texas Longhorns wave, except point the index and little fingers downward (and watch out for graduates from that school…).

Section/person: It often is necessary to make an adjustment to what a section is doing – and when you’re in really good form, it also is possible to adjust what a single person is doing, but you have to get their attention first. The general idea is to point to the section or person, and I find that when I’m indicating a section, I do it with a bit of a sweeping motion as opposed to pointing directly, as I do for one singer. This motion doesn’t mean anything by itself – it’s a sort of “shift key” for the signal that follows.

“Smile”: We sing better when we smile! So I indicate this by putting one finger on each corner of my mouth (either both index fingers or, more usually, a “V” sign with one hand). If we’re not enjoying being in ministry, what are we doing there?

Timbre adjustment: I started playing with this recently. A number of factors determine the whole choral sound; after intonation, timbre is one of the most important. It’s particularly significant that timbre helps to determine the “feel” or style of what the listener hears. It so happens that practically everyone has a pretty good idea of how certain types of pieces should sound even if they don’t have much formal musical training (actually, people are even better at knowing when what they hear doesn’t match the music: Imagine what your congregation will do to you if your choir sings a Mendelssohn work with an extreme country-western twang…

I describe timbre in terms of “resonance center,” the place in your vocal apparatus at which your singing appears to be located. People who prefer the operatic sound tend to have a resonance center which is low and back in their throat (“bel canto”), rock tenors focus their voices low and forward (“chest voice”), “floating” sopranos’ voices emanate from the upper back region (“head voice”), and really tired tenors – of which I’ve been one many times before – have a tendency to push their resonance centers high and forward (aka “shouting” or “trying too hard”).

My signal for adjusting timbre is to point sideways, then to move my hand horizontally and/or vertically. The initial pointing direction indicates where the mouth is and the shift indicates which way I want the resonance center to move.

Because this can also be combined with the “section / person” cue above, you can make adjustments of all types which can make the group timbre absolutely phenomenal!

“Listen” => think of total sound: It’s far better to remind everyone to think about what they’re doing so that they develop a habit of assessing their surroundings so that they can adjust accordingly. And so I don’t usually give the thumbs-up sign (which a lot of people use to sign “you’re going flat!”); rather, I’ll cup a hand behind my ear to encourage everyone to listen and think. And it works!

“Vertical” (tone) – “Two/three fingers”: Most of us just don’t open our mouths widely enough when we sing. This affects intonation, diction, timbre,… well, just about everything! And so many directors spend a lot of time harping on the importance of “getting the jaw down” or whatever phrase they prefer.

You can sign this easily by stroking both sides of your face in a forward direction (whether you use one hand or two is your choice). The gesture suggests pulling the cheeks inward, and this, in turn, implies that you have to open your mouth. Alternative: open your mouth and stick two or three fingers in it – if you don’t mind looking stupid…

“Maintain phrase” => no breath: In addition to not opening our mouths widely enough, we also have the unfortunate habit of breaking our phrases with unsightly breaths. It truly is amazing to see how large numbers of people can have the same idea of where to break the textual line in music!

I remind my singers to “carry” the note they’re singing by moving my hand slowly from one side to the other (by the way, Paul Salamunovich has been doing this for longer than I’ve been alive…). It’s a way of telling everyone that “line” is essential. And Paul S. (above) also mentions that this helps to keep the notes moving (rather than stagnating).

Beat pattern: There are different schools of thought on this matter. Some people claim it’s essential to maintain the beat pattern no matter what; others would rather use it only if necessary because they’re concentrating on directing the expression of the piece. You can take your own approach to this; after all, I’m sure you’ve found that good choral directing involves a little skill, a little knowledge, and a tremendous amount of pragmatism and love.

Fermatas: The key to directing fermatas as my friend Hanan Yaqub taught me awhile back, is to ensure that you give the preparatory.This beat must be:

According to the tempo of the section to which it’s leading.

(Generally) on the beat pattern stroke just before whatever follows the fermata.

If necessary, a reiteration of the last stroke in the fermata, i.e. the first stroke indicates the ending of the fermata – and its replication cues the choir with tempo and whatever else a preparatory beat can convey.

“Last time” (fist): This is an old performance signal. You just make a fist and hold it out with the finger side toward the choir (kind of like the Sixties’ “Black Power” salute, except without the ethnopolitical implications and statements). It’s just a reminder, although it’ll save your hide if you and the choir need to escape from the middle of an indefinitely-repeated vamp.

“Again” (circle): I indicate this by drawing a circle in the air with an index finger (the circle’s turned so that people to either side can see that it really is a circle. This too is an old performance standard.

“Hit my hand”: Occasionally our vocal projection needs a boost, and so I’ll put my palm towards the choir to remind them to hit my hand with their voices (by the way, this works beautifully with children’s choirs – you do want them to sing with a full tone rather than a sickly, breathy one, don’t you?

Anyway, “hit my hand.” There’s an old joke about this…

“More” / “less” / “a little”: Once your choir gets in the habit of watching you most of the time, you can go beyond merely using the simple signals. For instance, you can combine them in “shift key” style with a sign to indicate how much adjustment you need.

“Yes” / “good” / “thank you” (mouthed): Your choir will love this one; positive reinforcement is great stuff! Oh – remember to smile too!

“Breath support”: I don’t make a big deal of this. Rather than making a big signal, I’ll just put my hand on my stomach and let empathic response take over.

Incidentally, there’s a huge benefit to using nonverbal signals during rehearsal: Your choir will get in the habit of looking for them! And – what do you know? – their eye contact with you and the congregation will improve tremendously!

Guiding Principle VIII: Have a sense of humor (learn to laugh at yourself, and you will then never run out of material…).

One last idea: don’t be afraid to give the choir the opportunity to have some fun / laughs at your expense. There’s a corollary to Murphy’s Law which goes “you have taken yourself too seriously”), and for many of us it’s absolutely true. Foibles are God’s way of reminding us that we haven’t arrived, but they also are His reminders that He’s making progress in our lives (no, I didn’t say how quickly…). “Laugh, and the world laughs with you; cry, and you cry alone” is all too true in today’s world. Do your part to make this a less prideful place to live!

Conclusion:

Well, let’s see. First of all, I had absolutely no idea that this writeup was going to be so huge… but I think every bit of material here is worth examining. The reason for this, of course, is that at the very worst you’ll be no better off than you were before dropping by. At the best, you’ll have ideas you can explore and adapt as you continue to work with your choir.