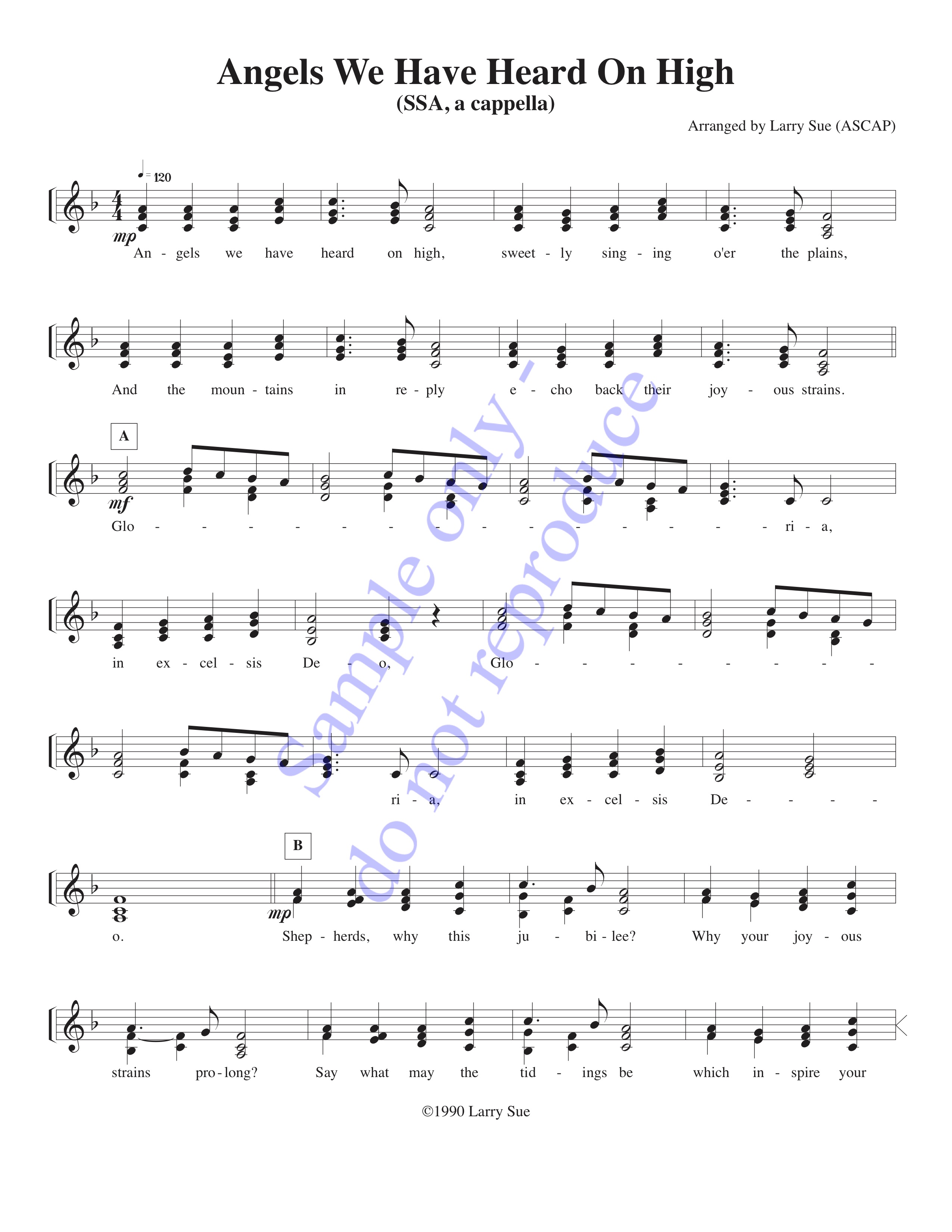

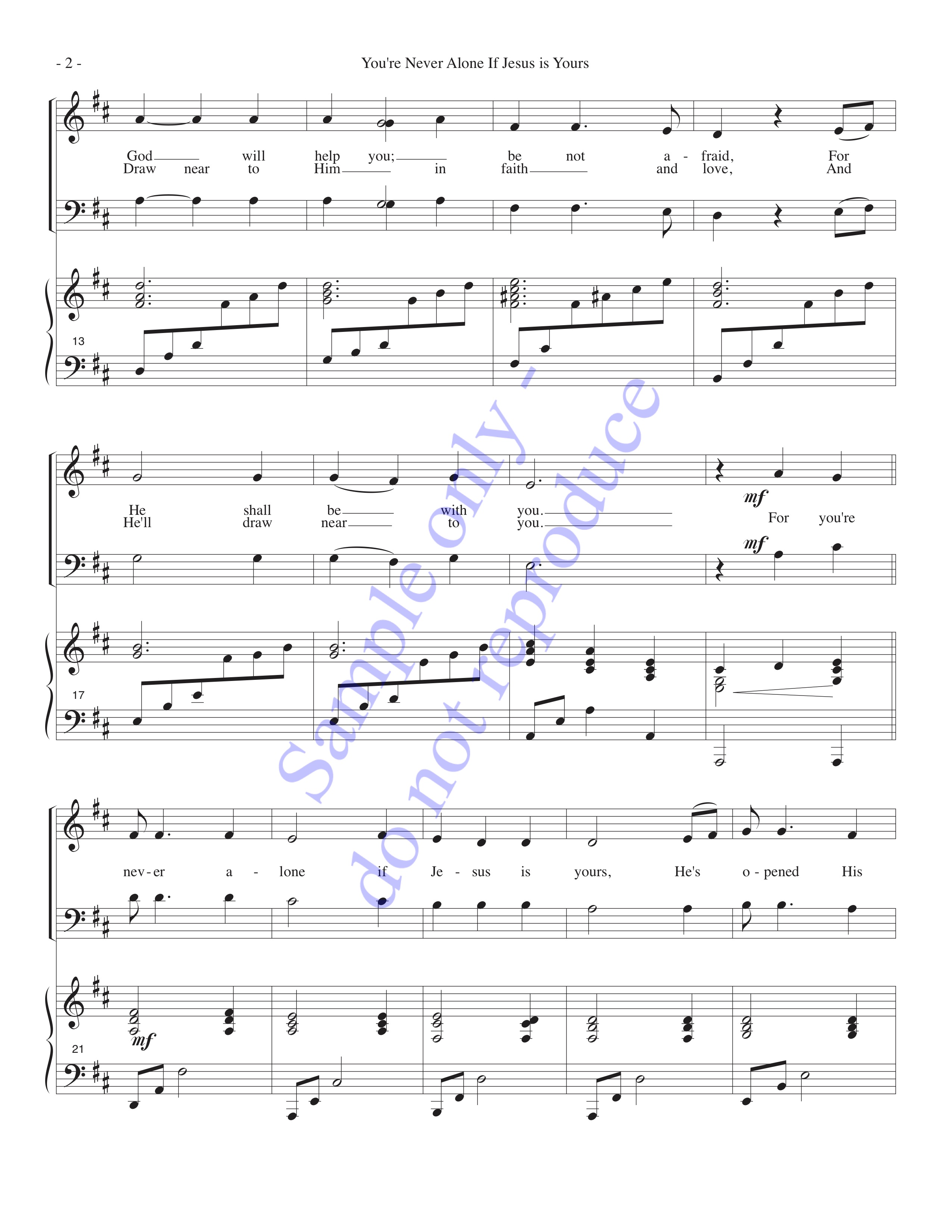

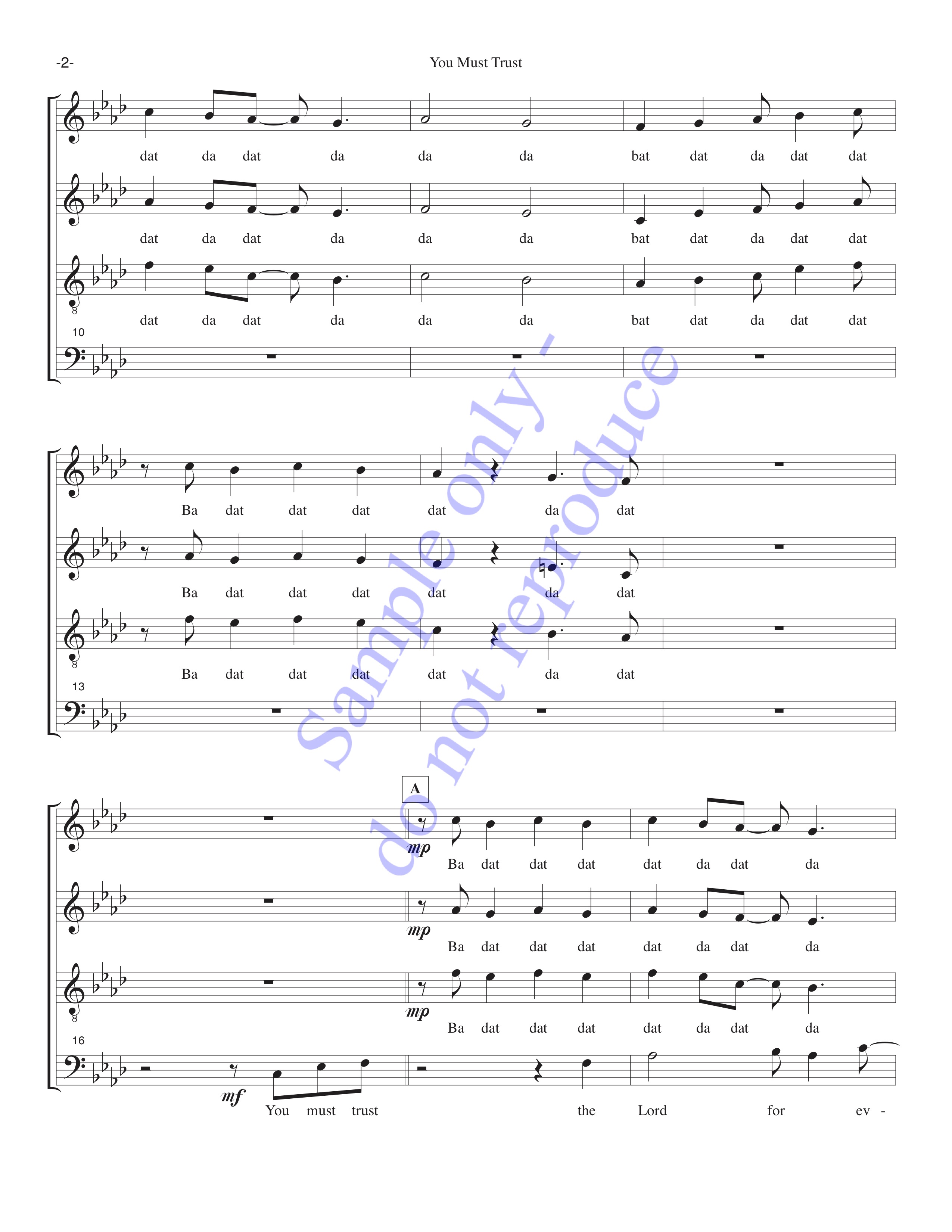

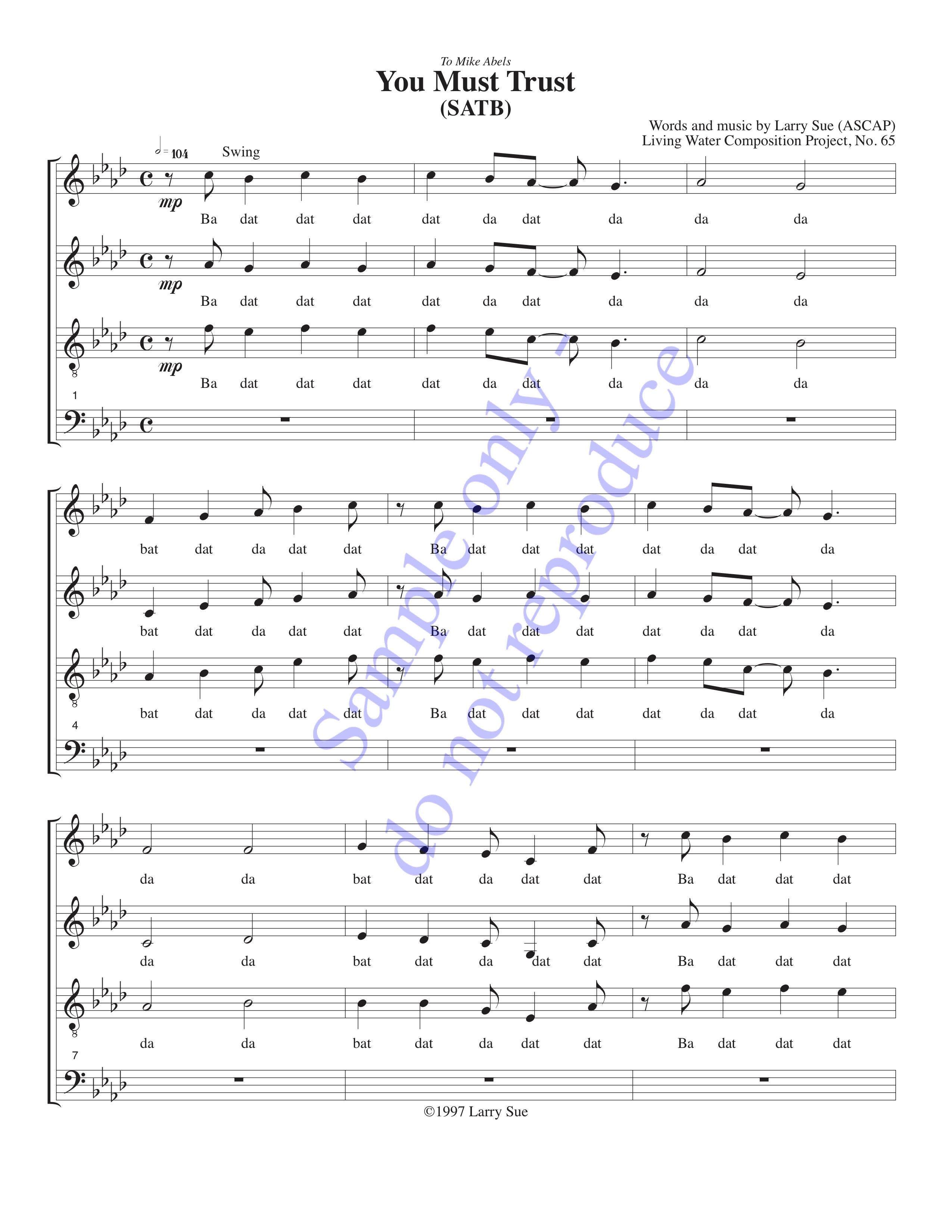

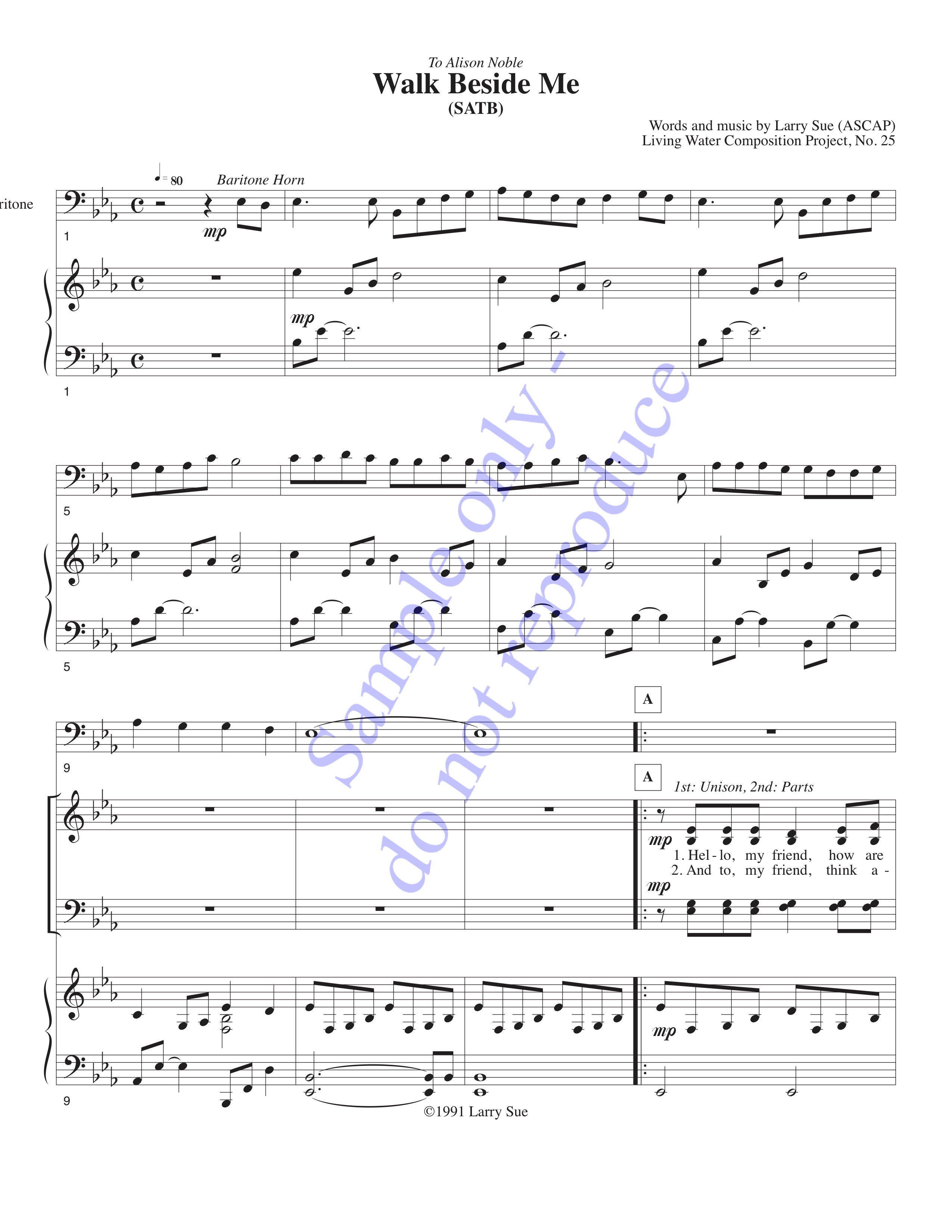

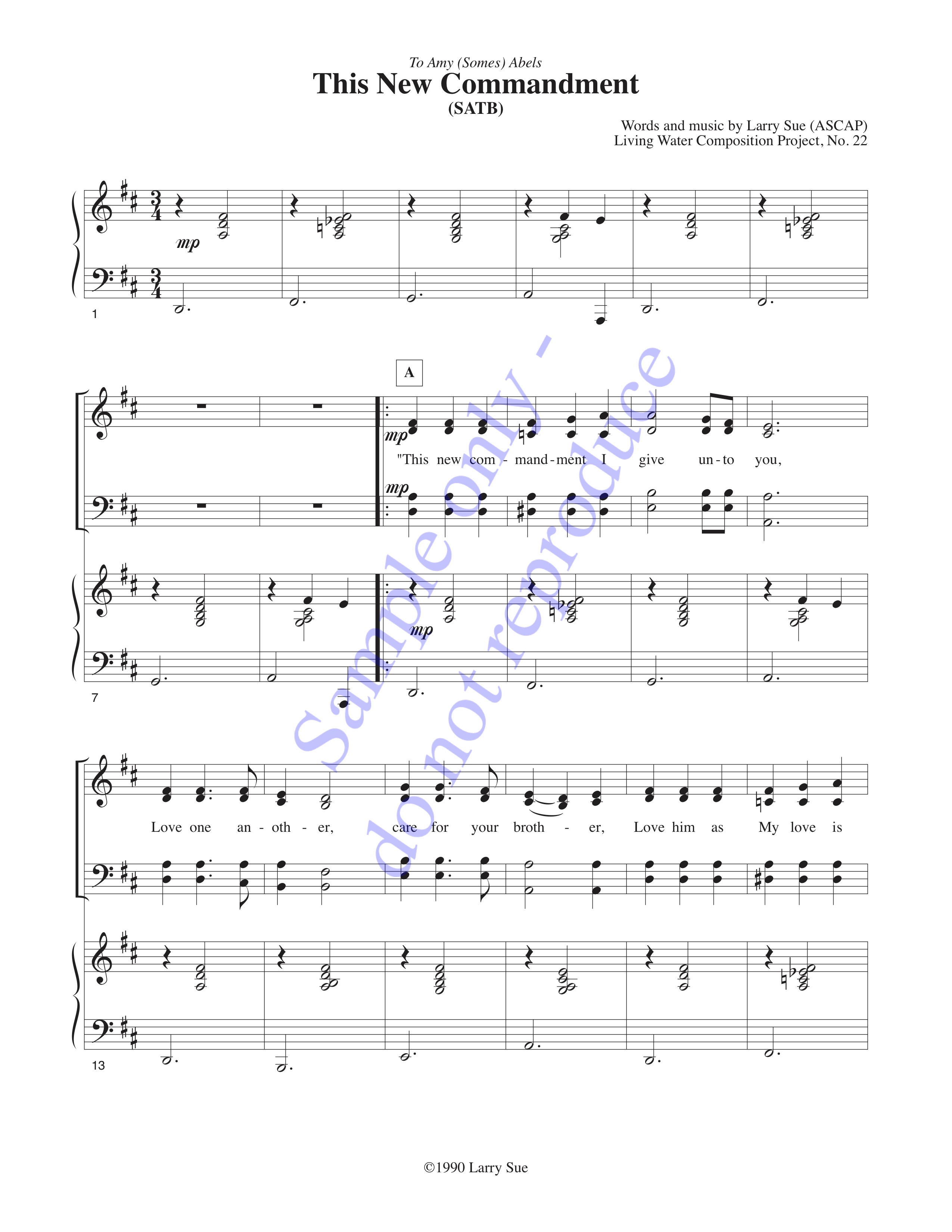

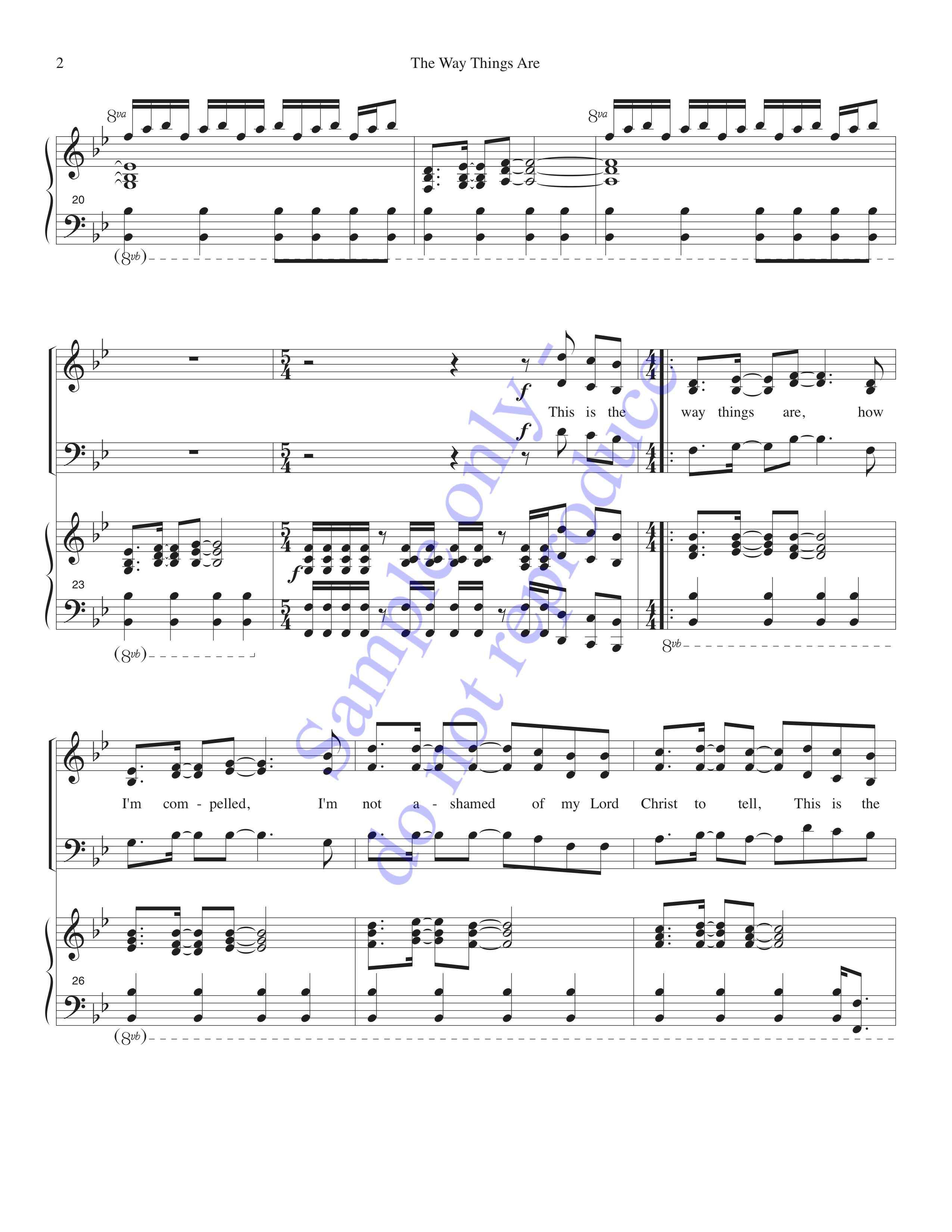

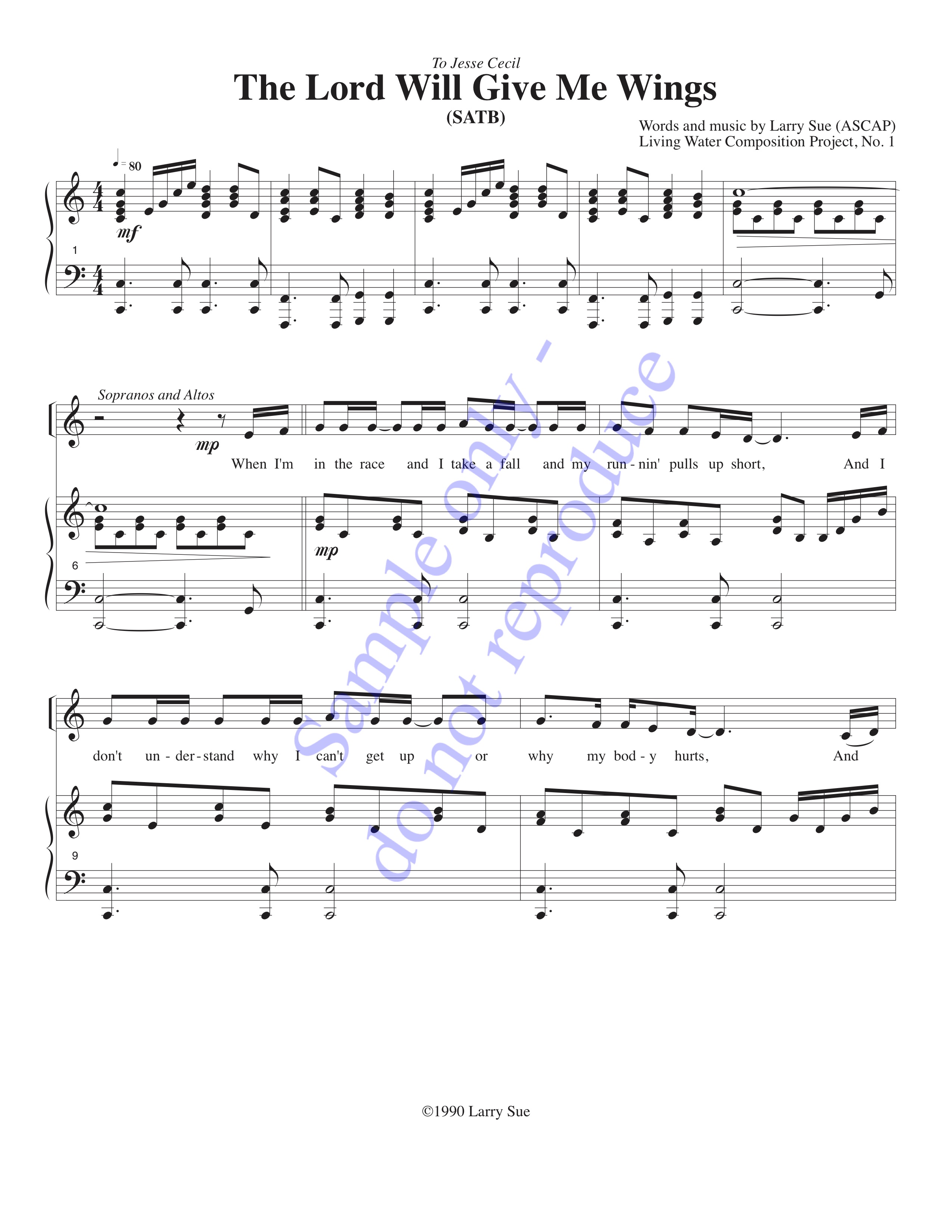

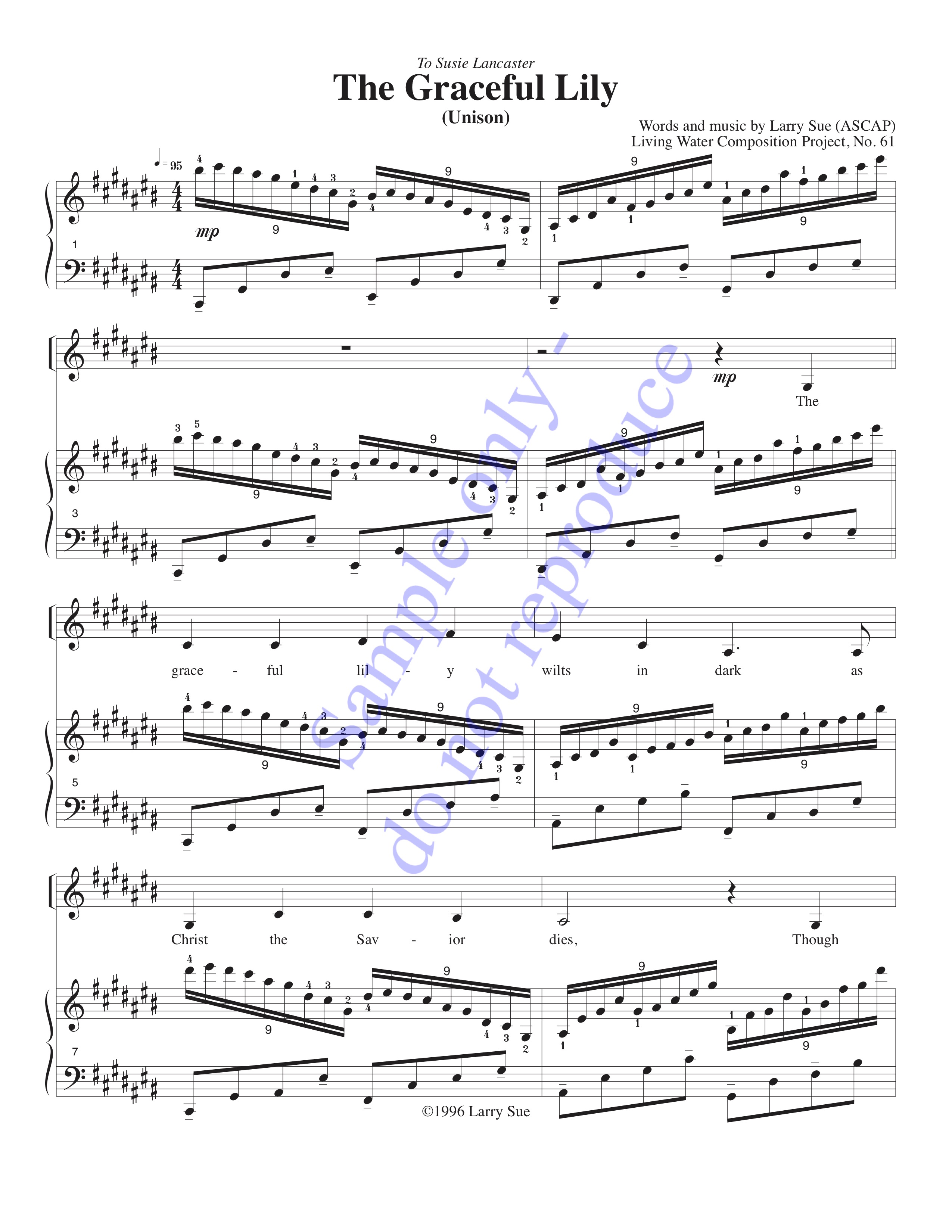

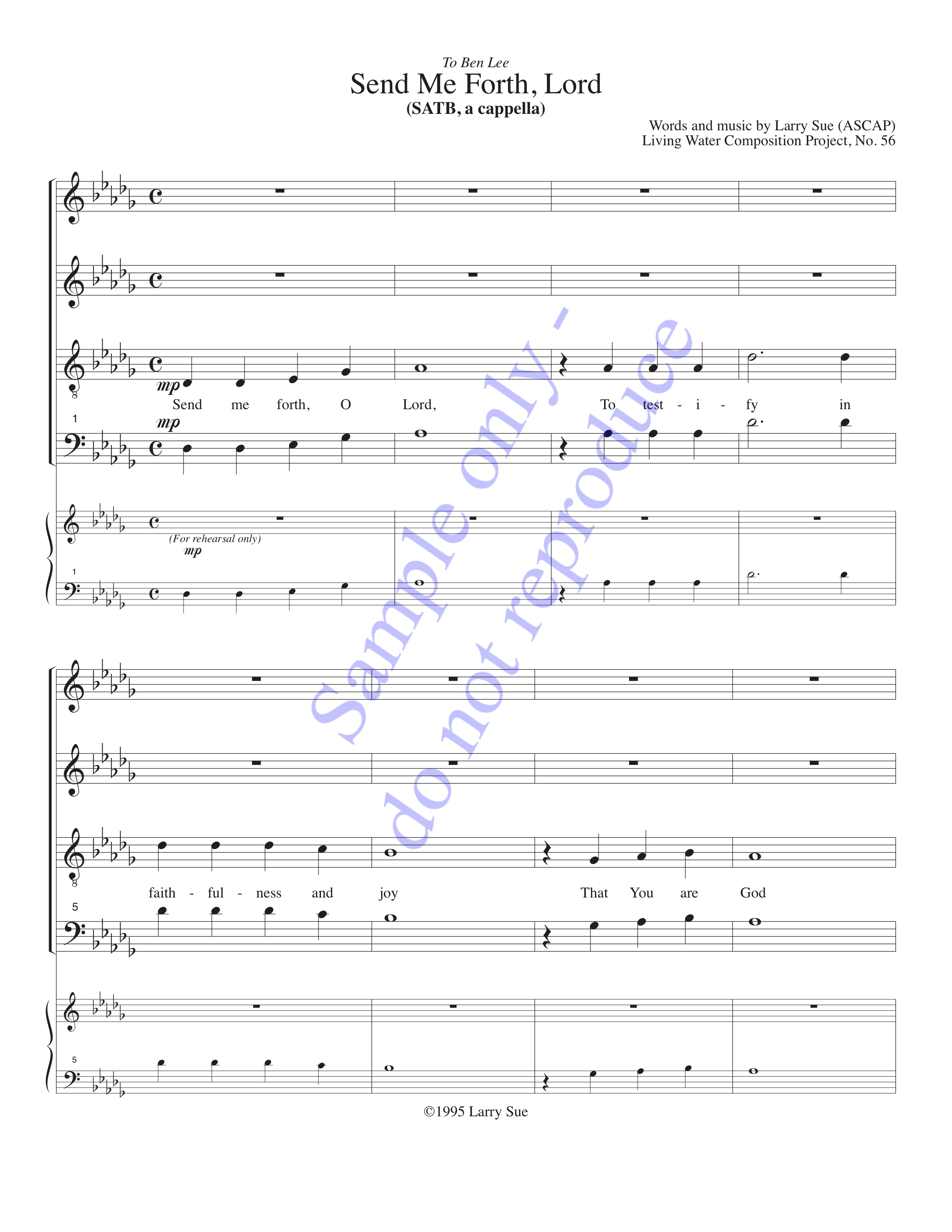

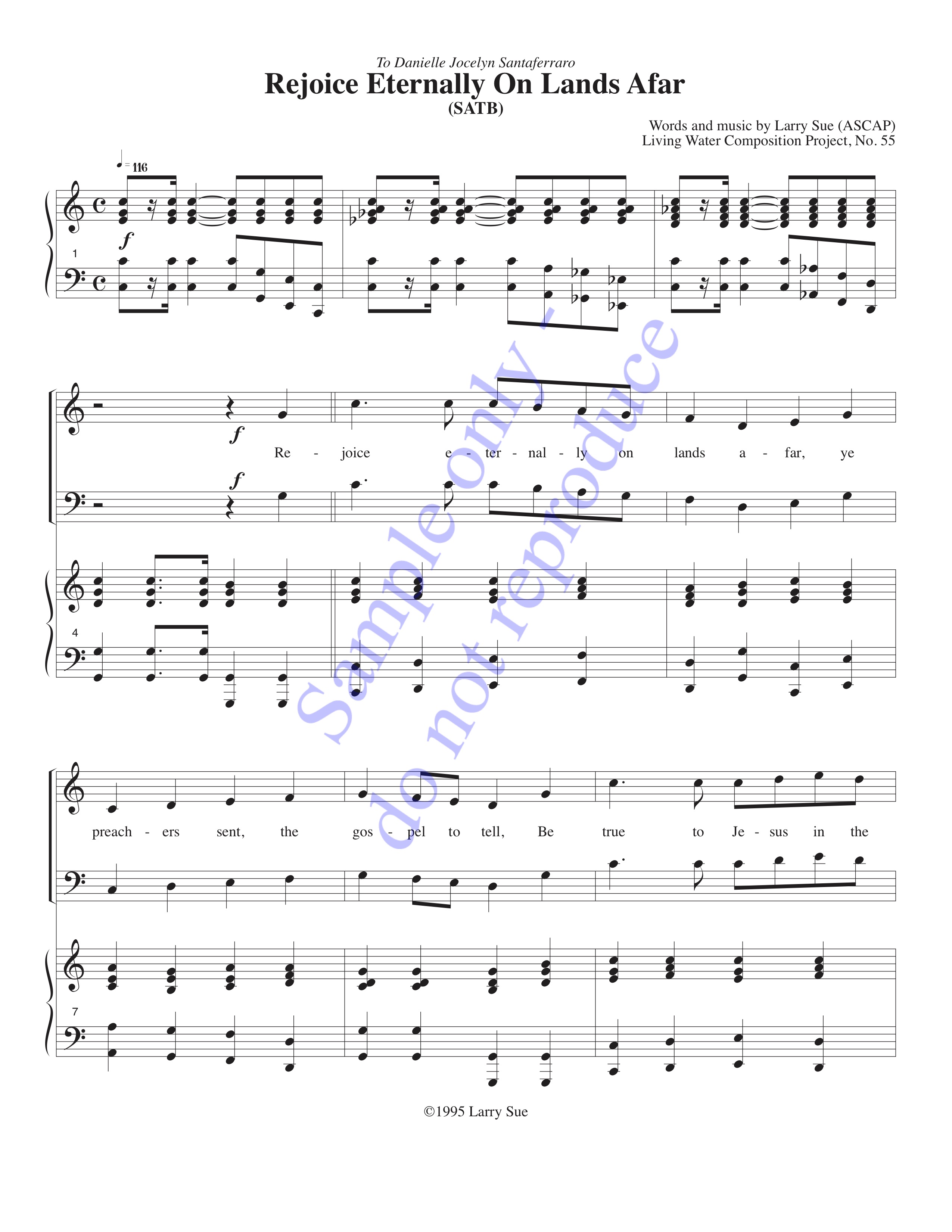

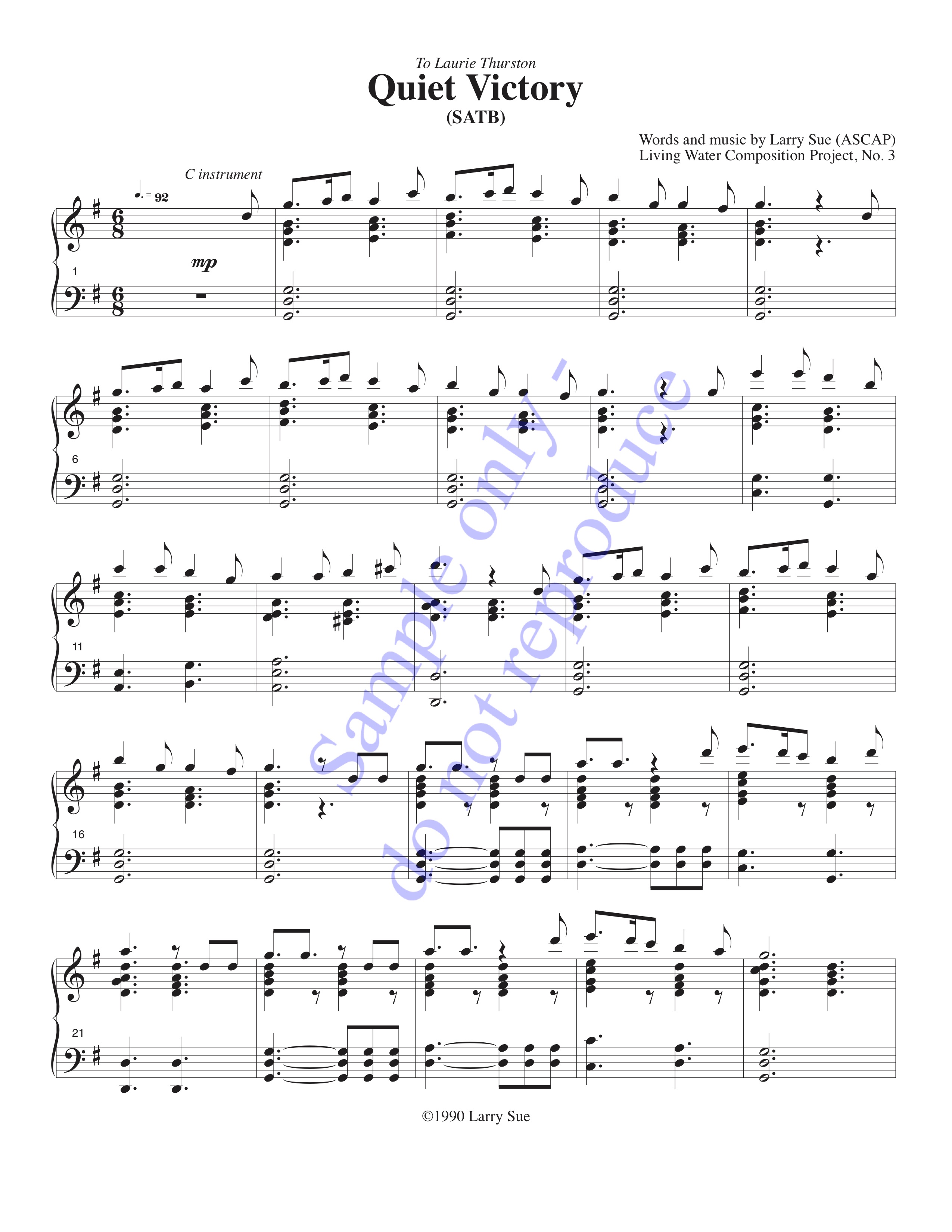

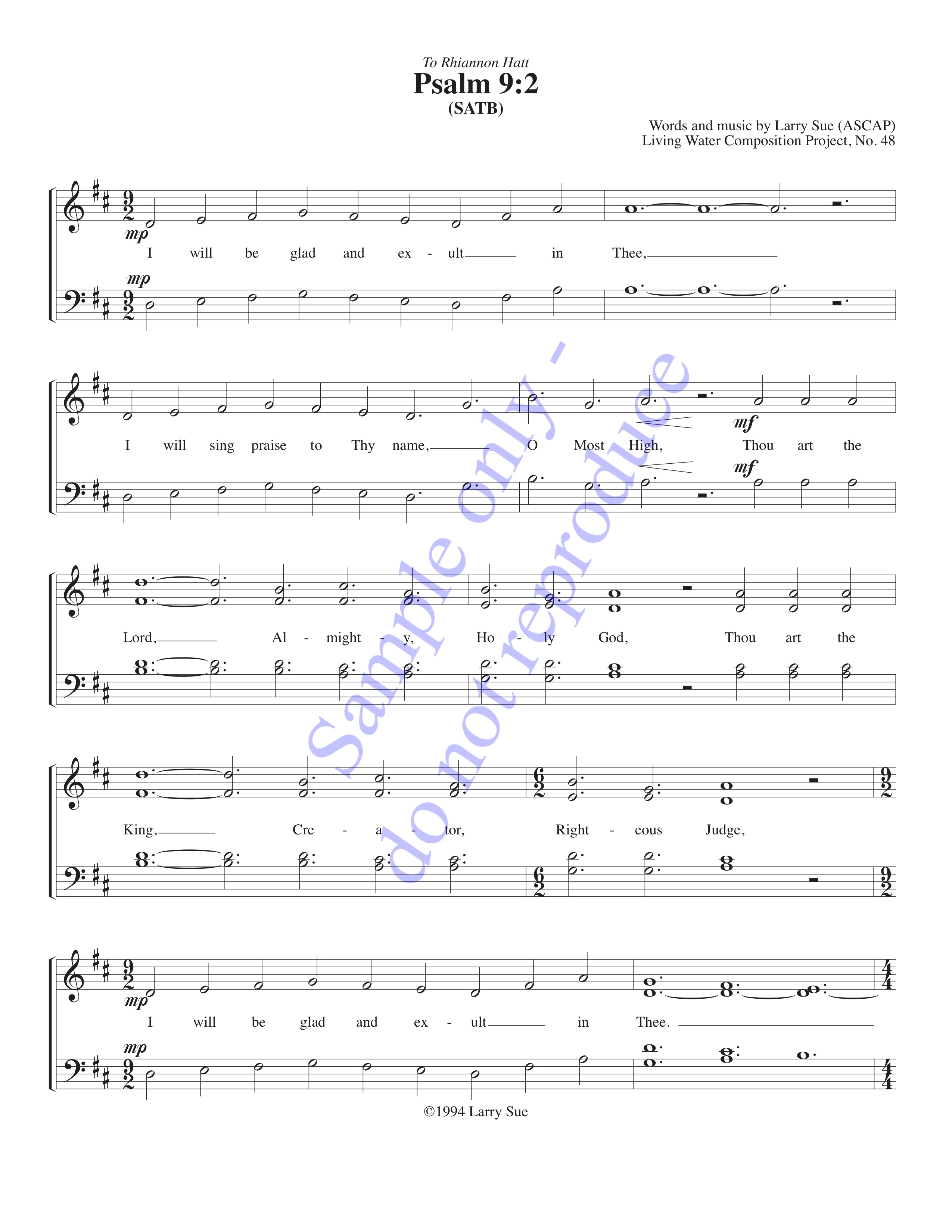

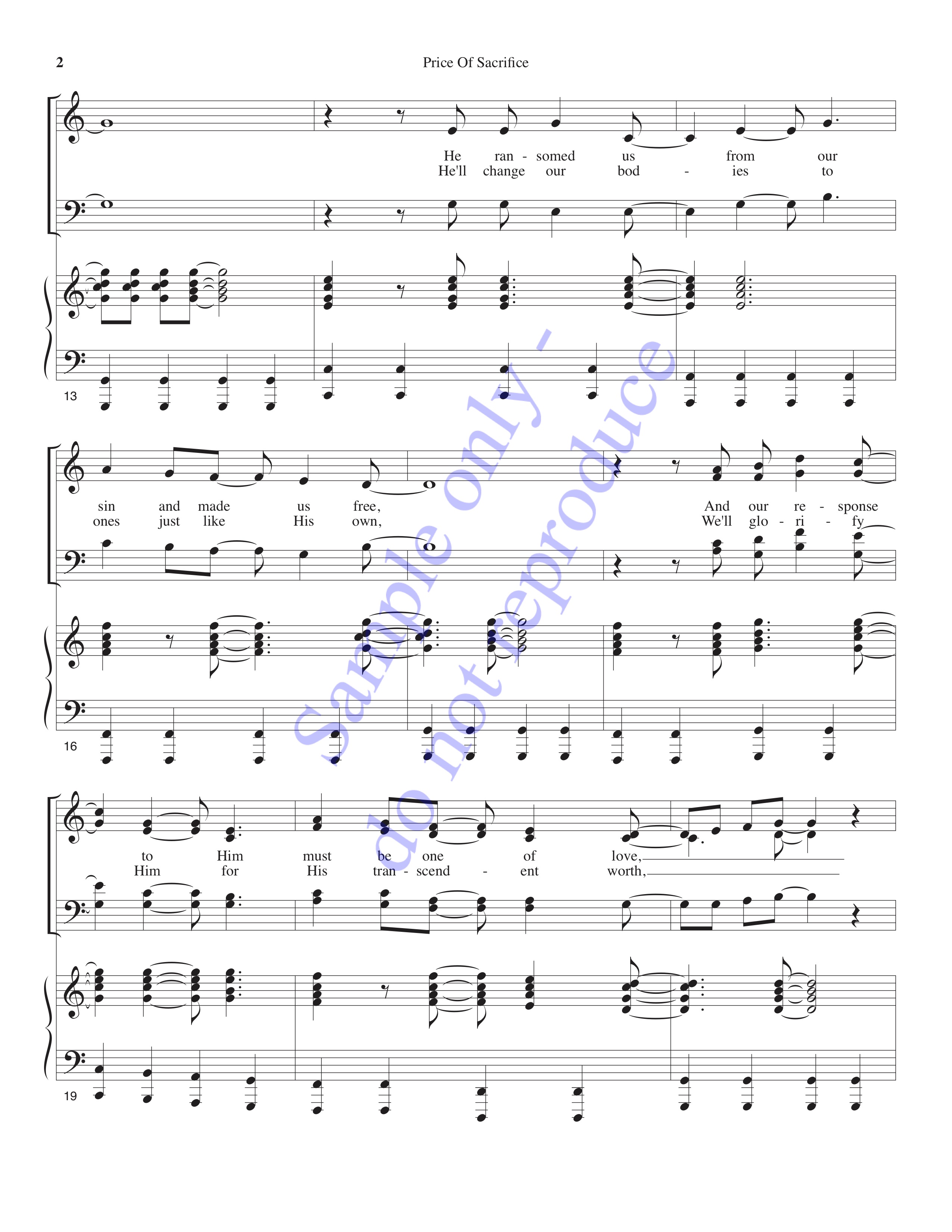

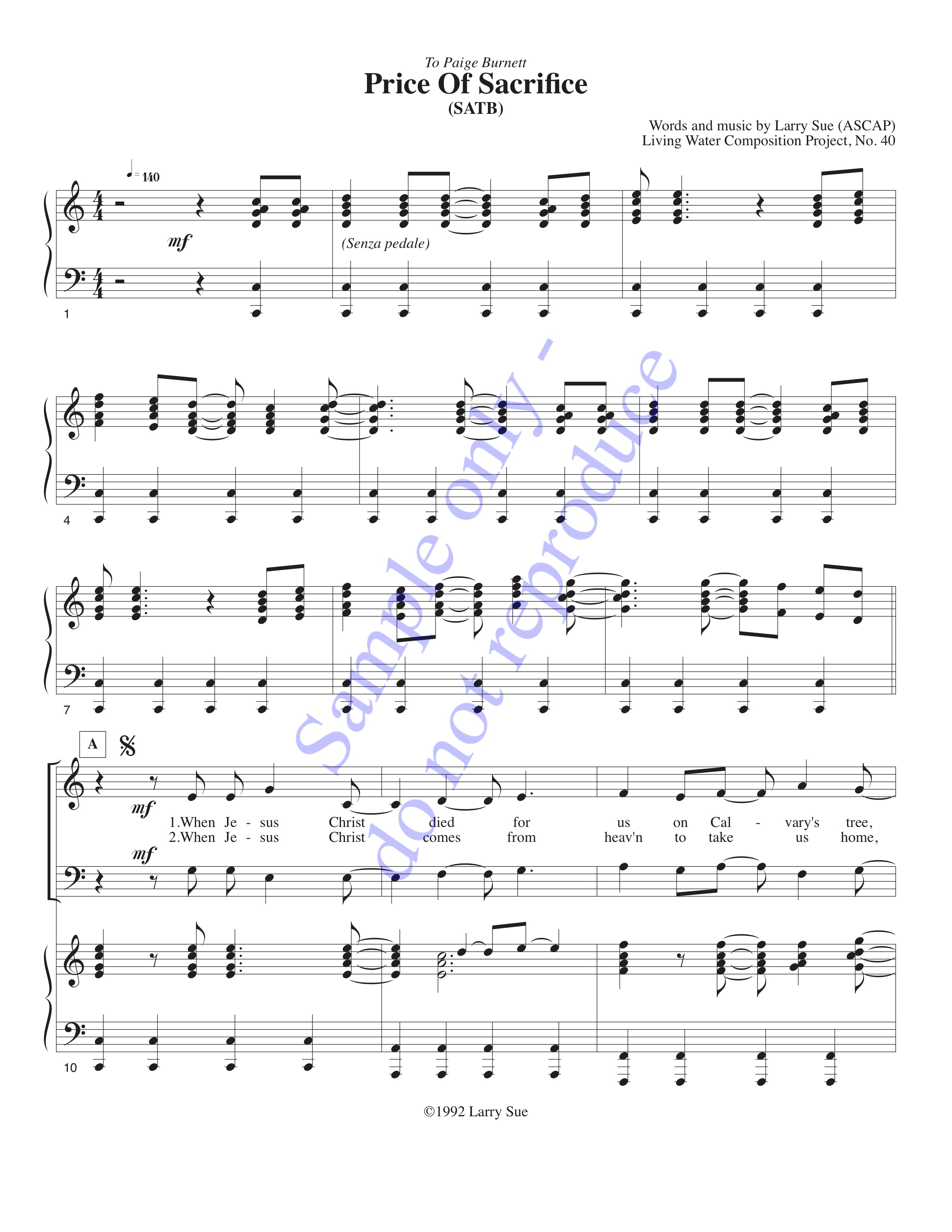

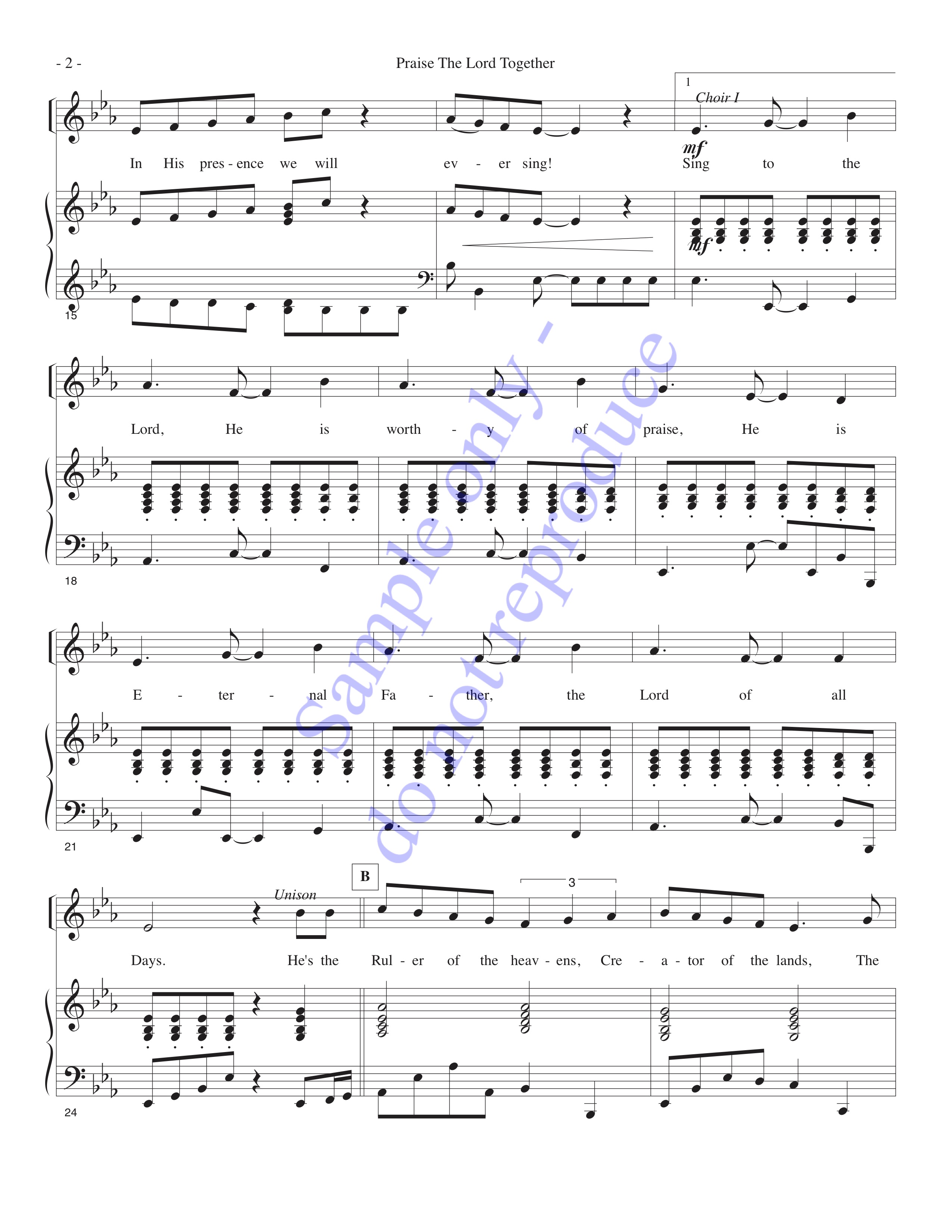

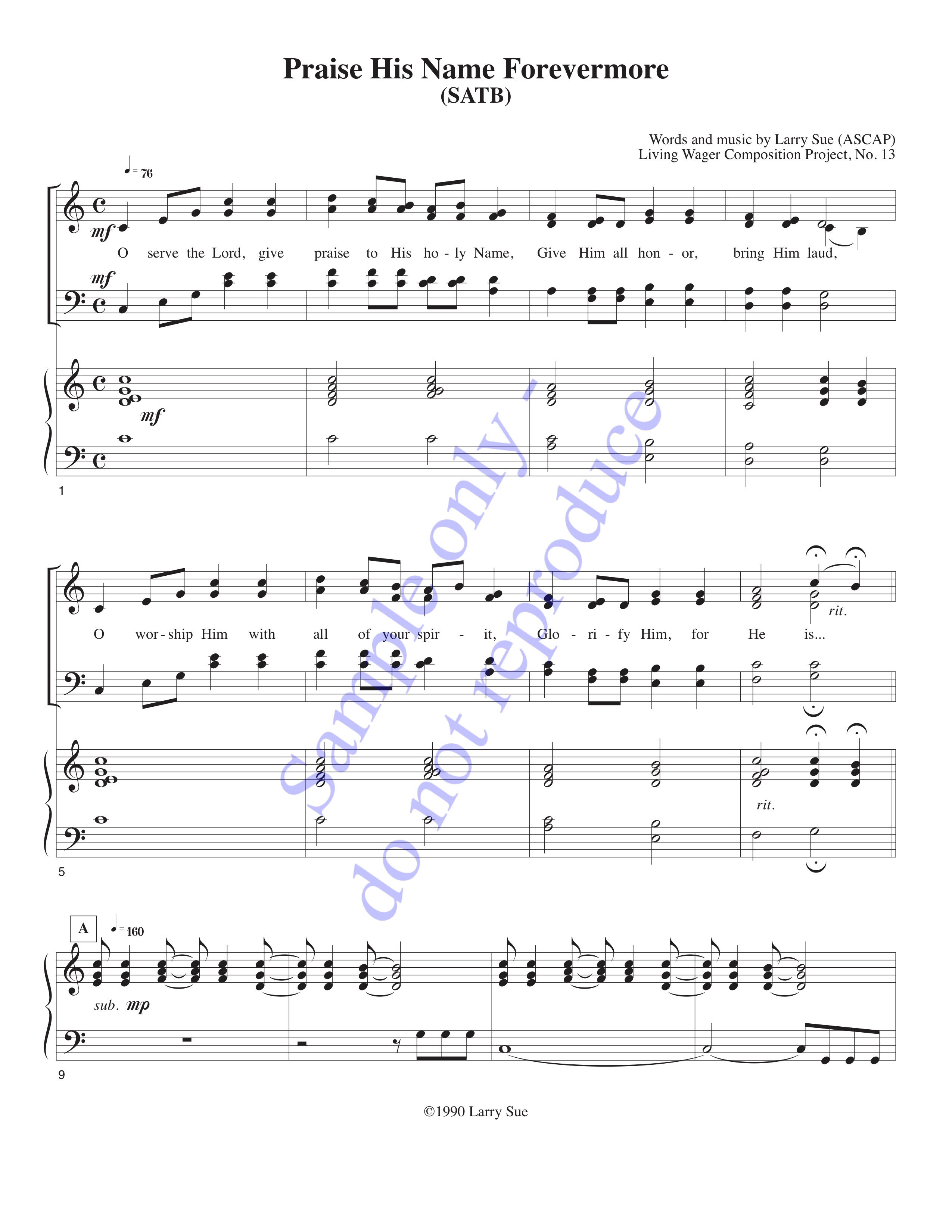

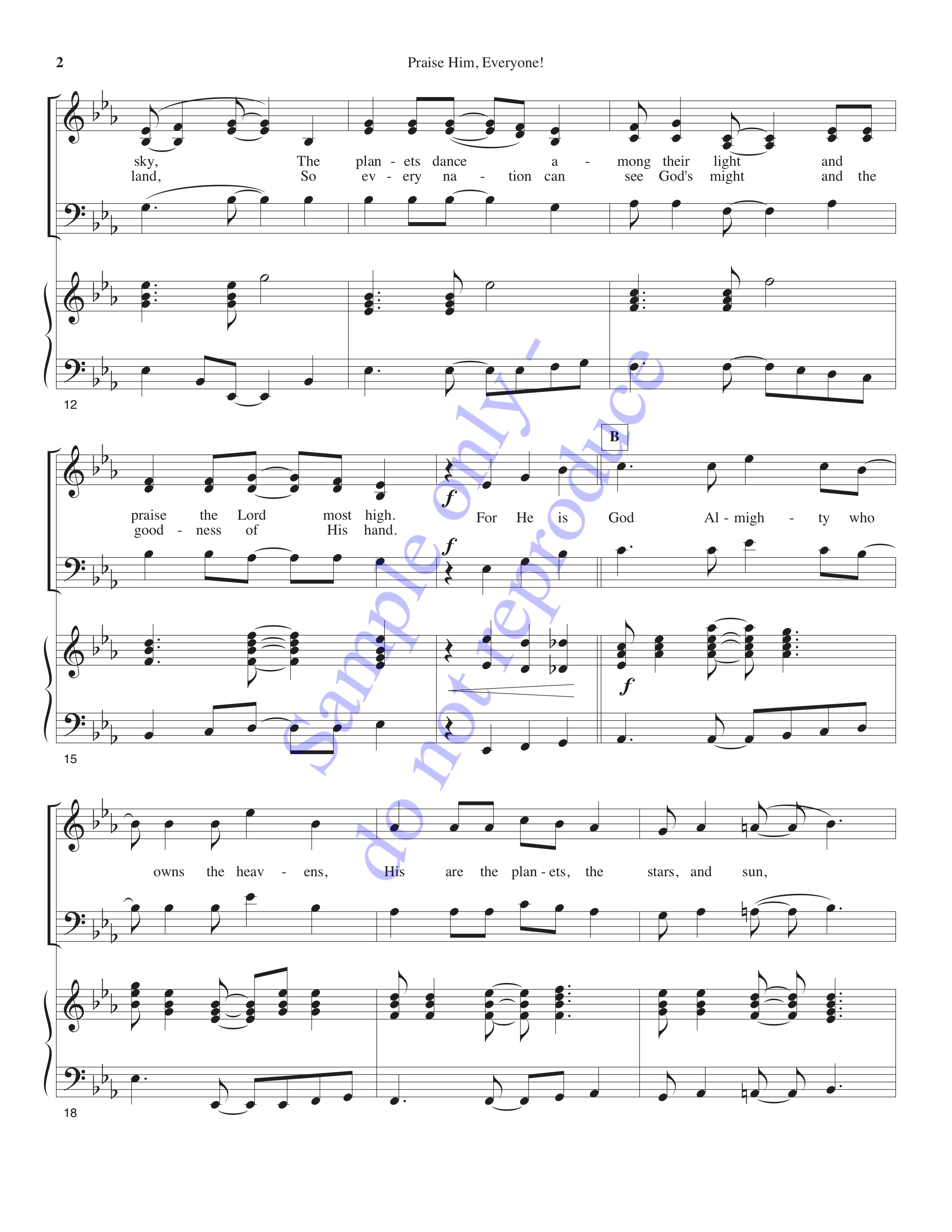

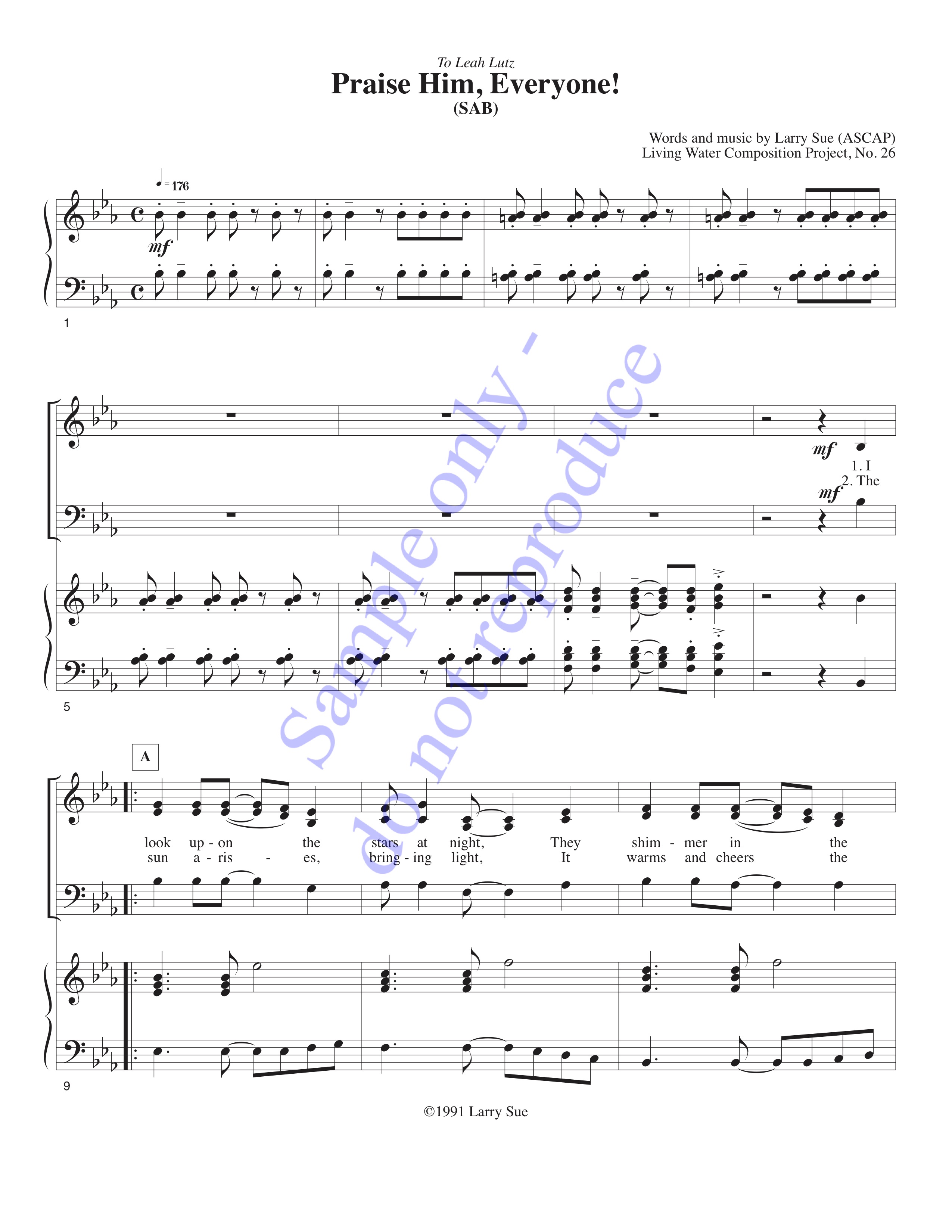

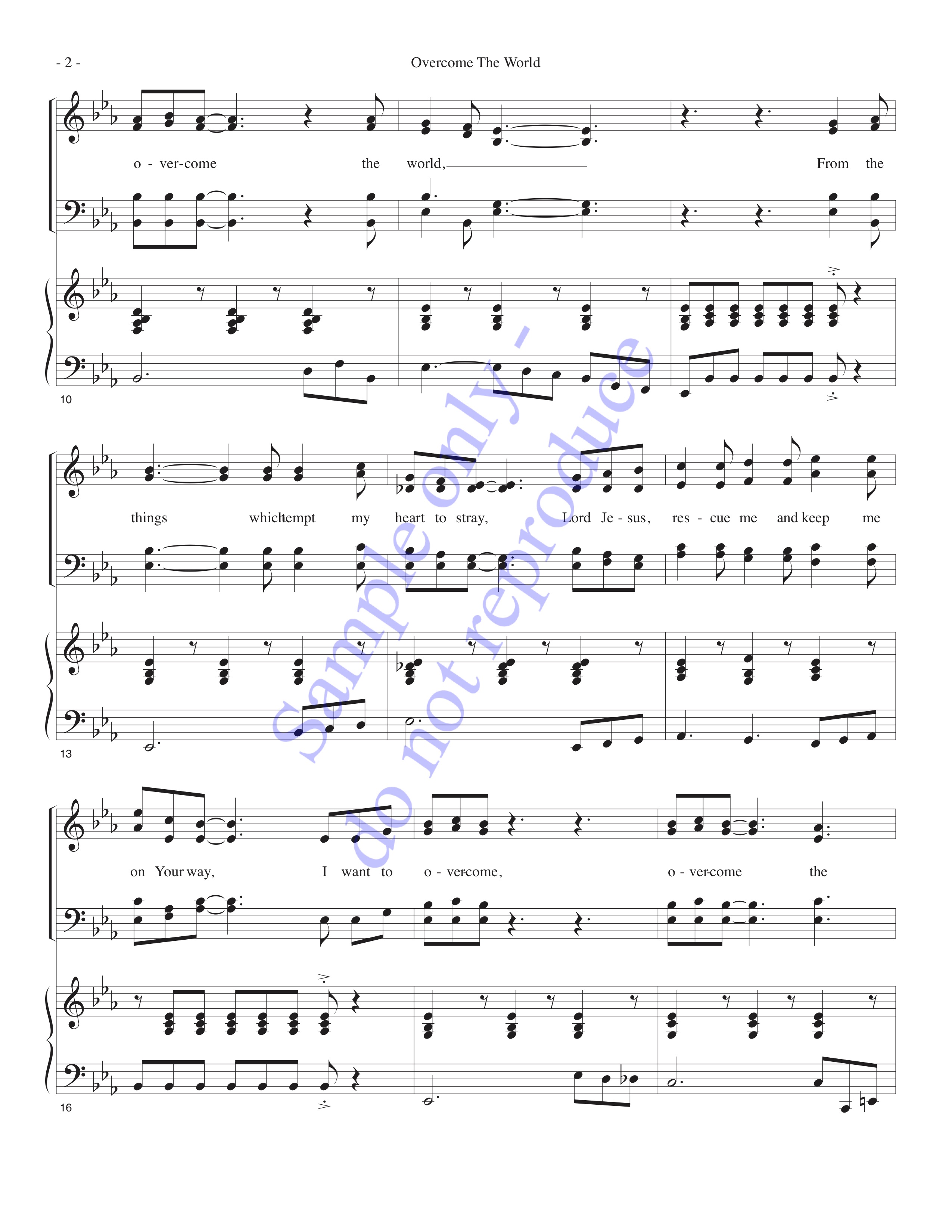

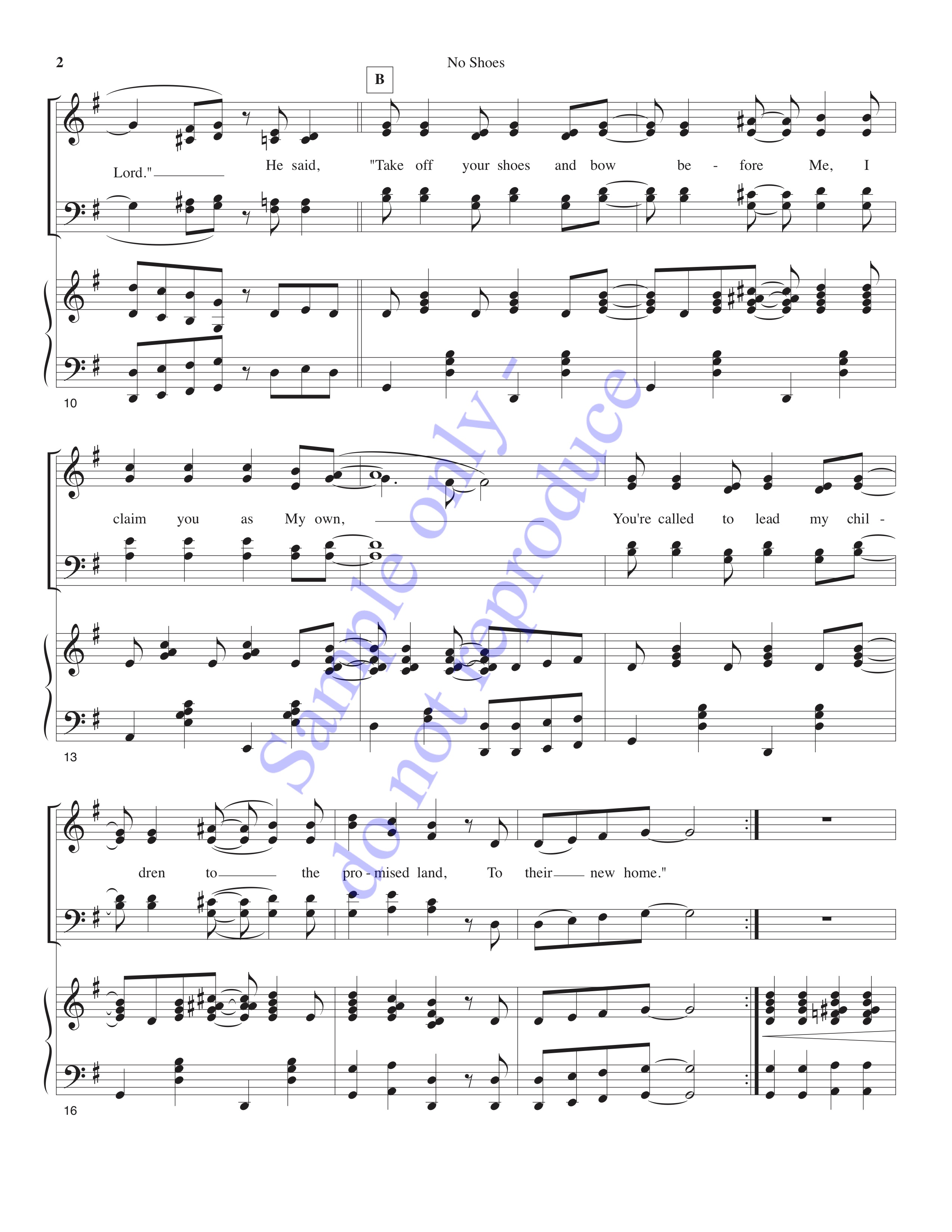

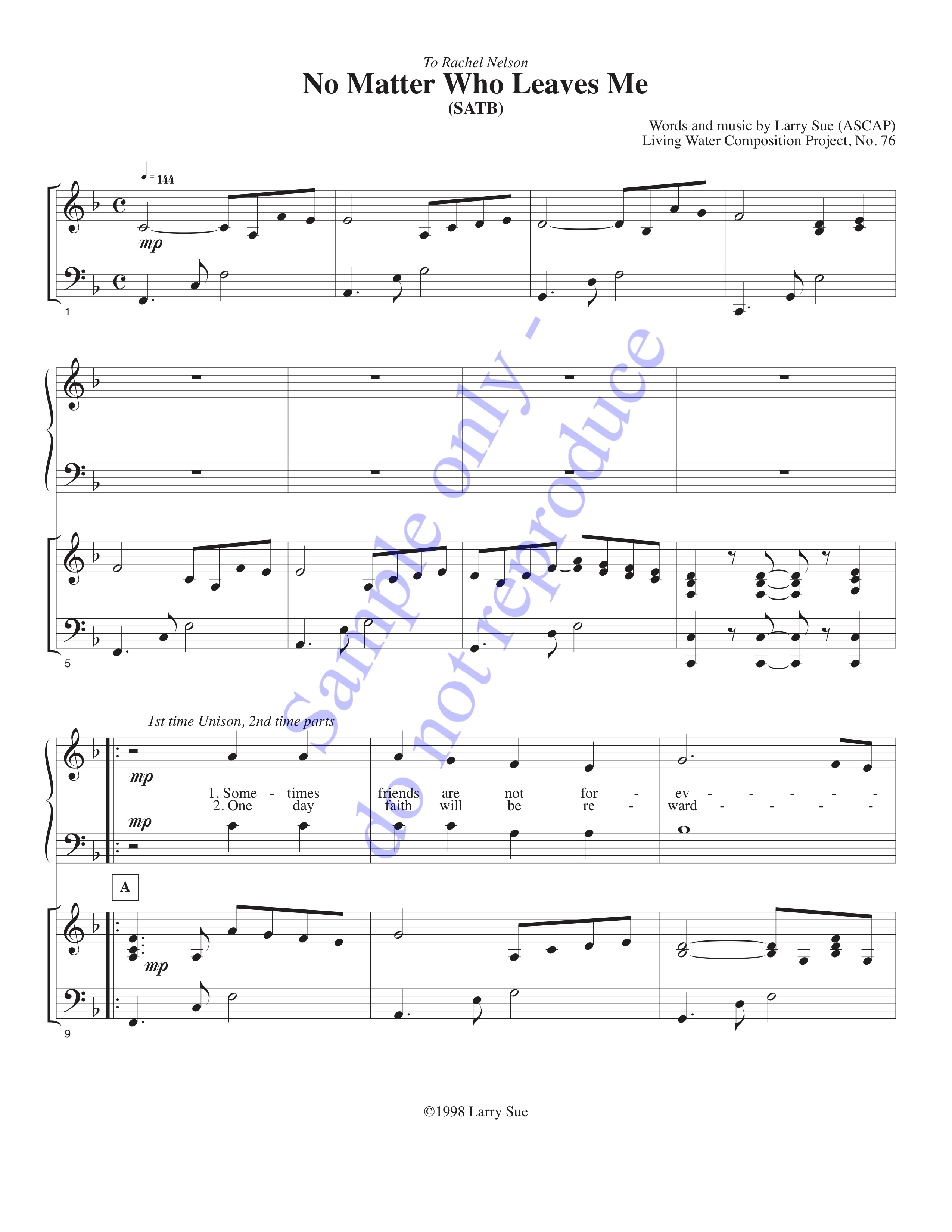

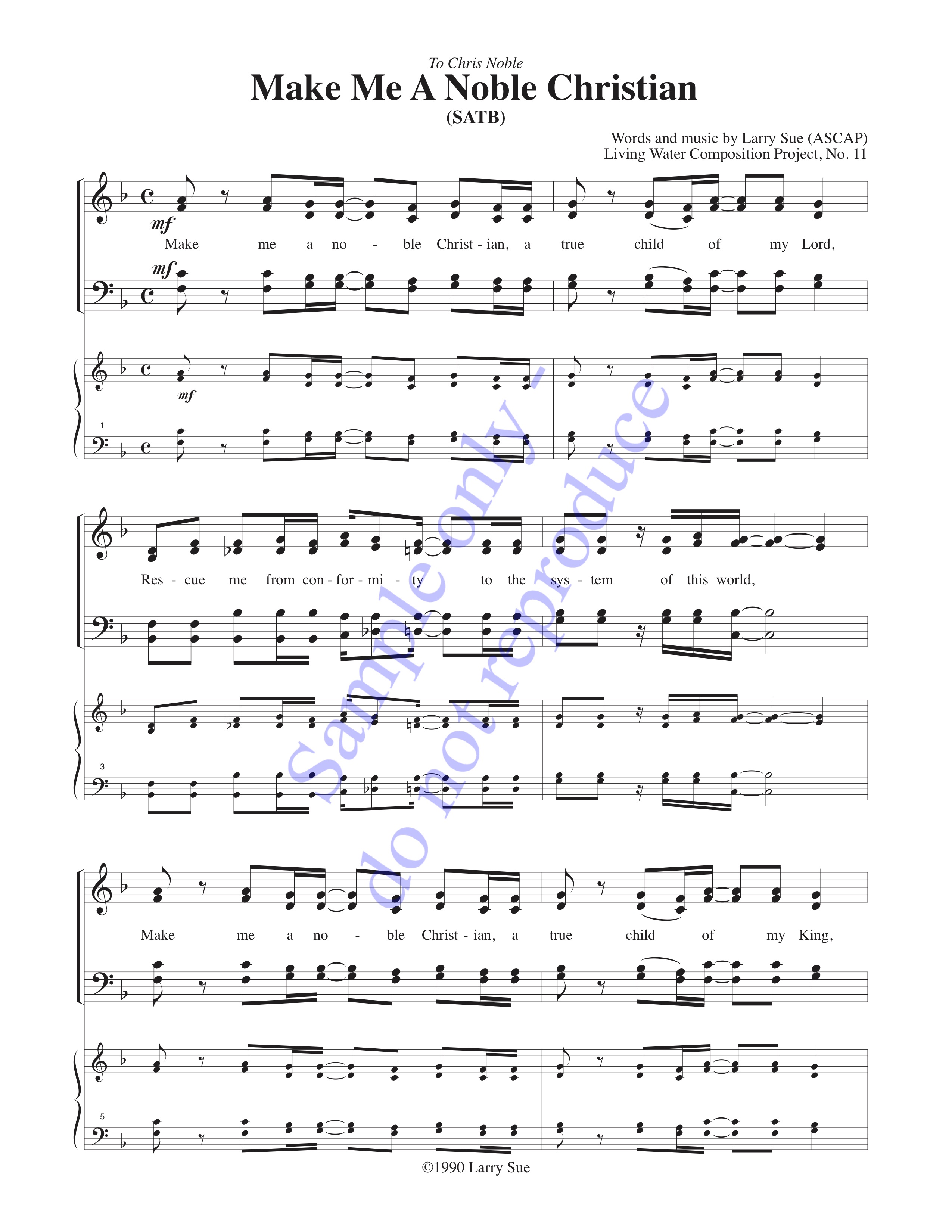

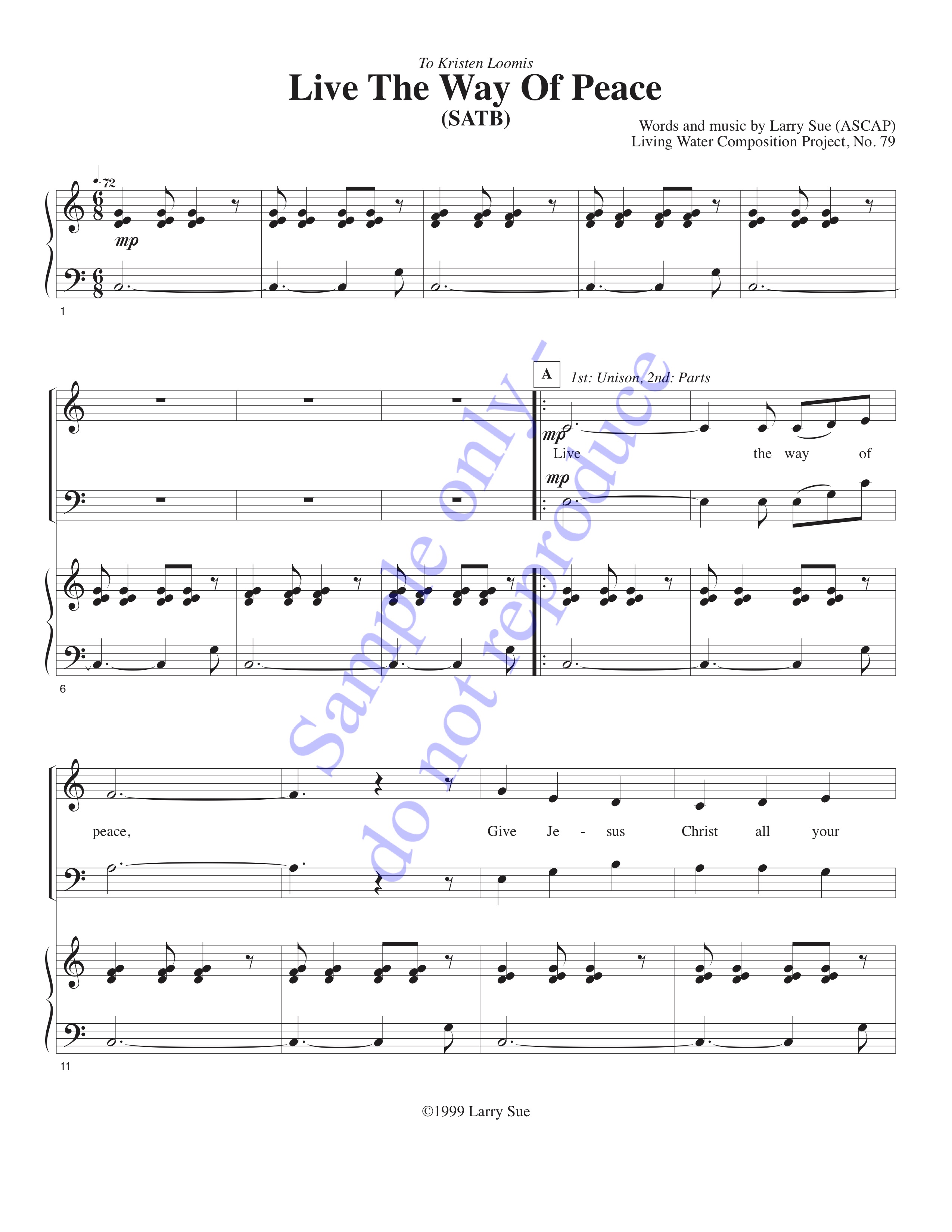

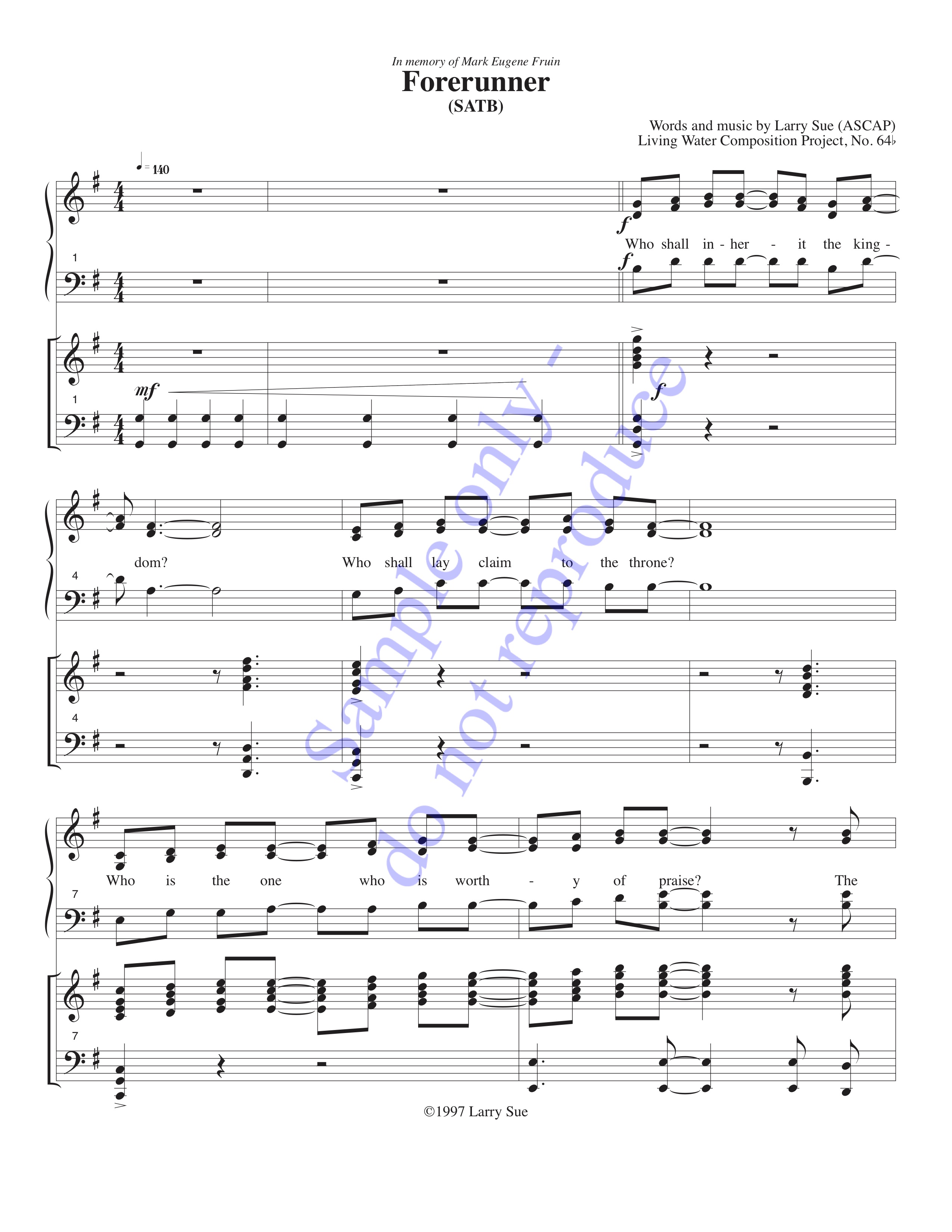

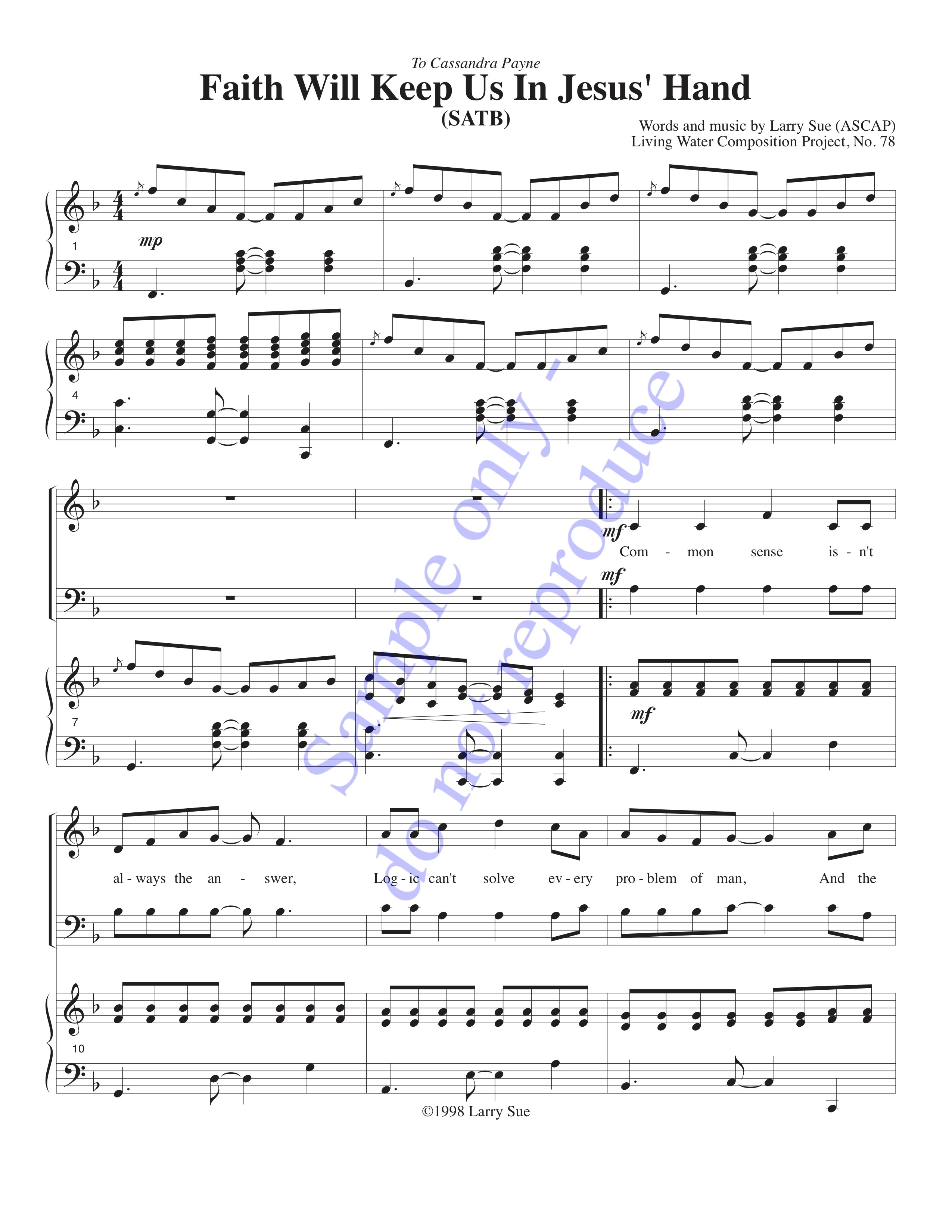

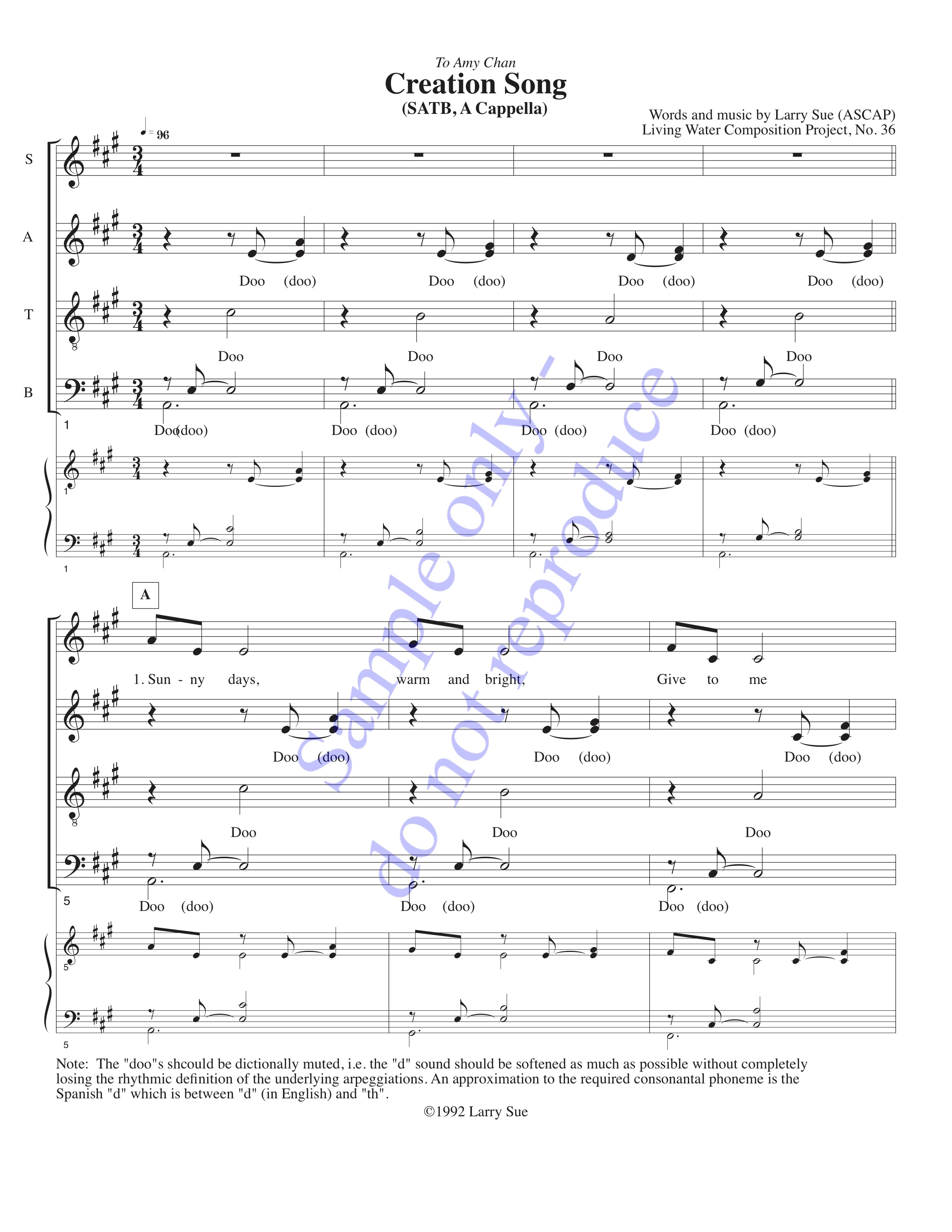

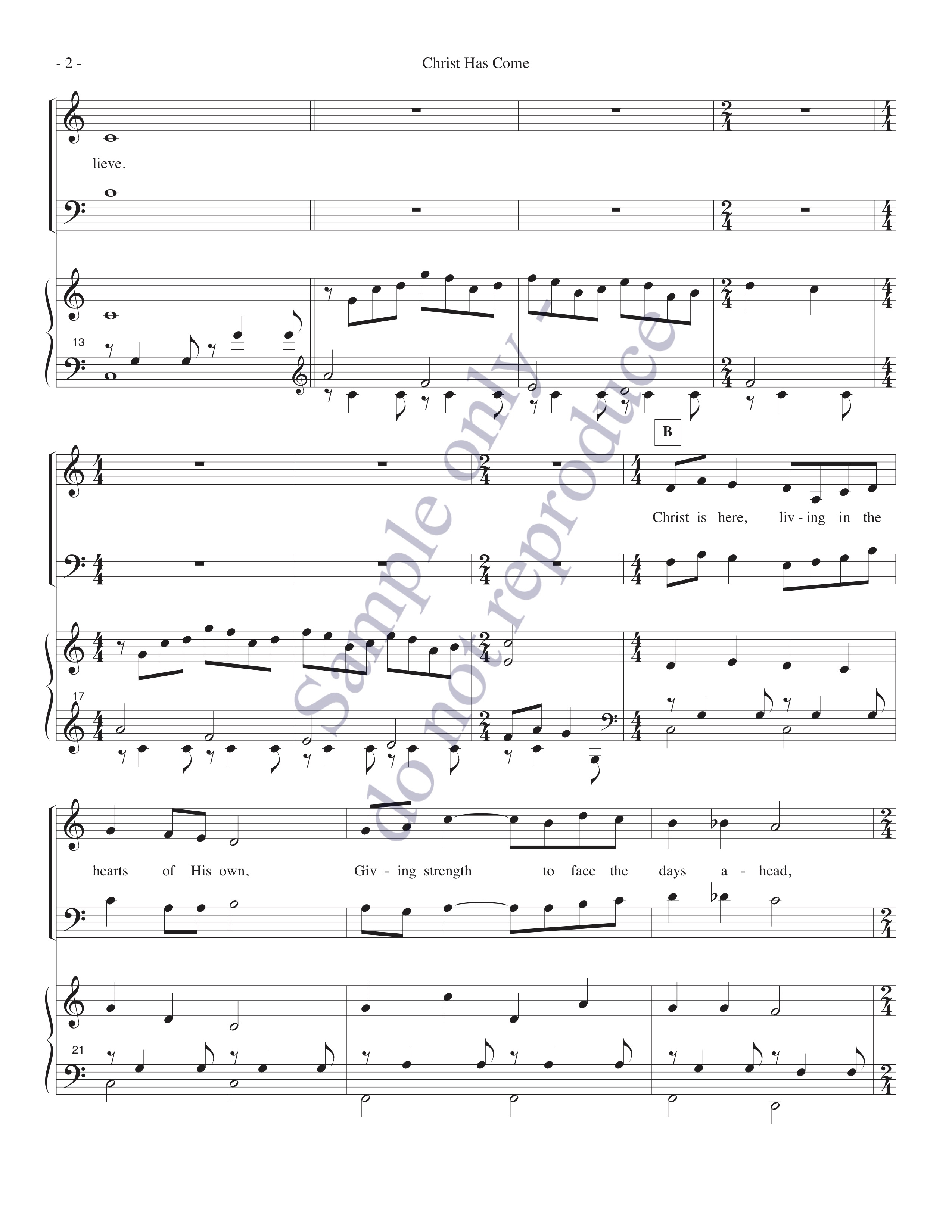

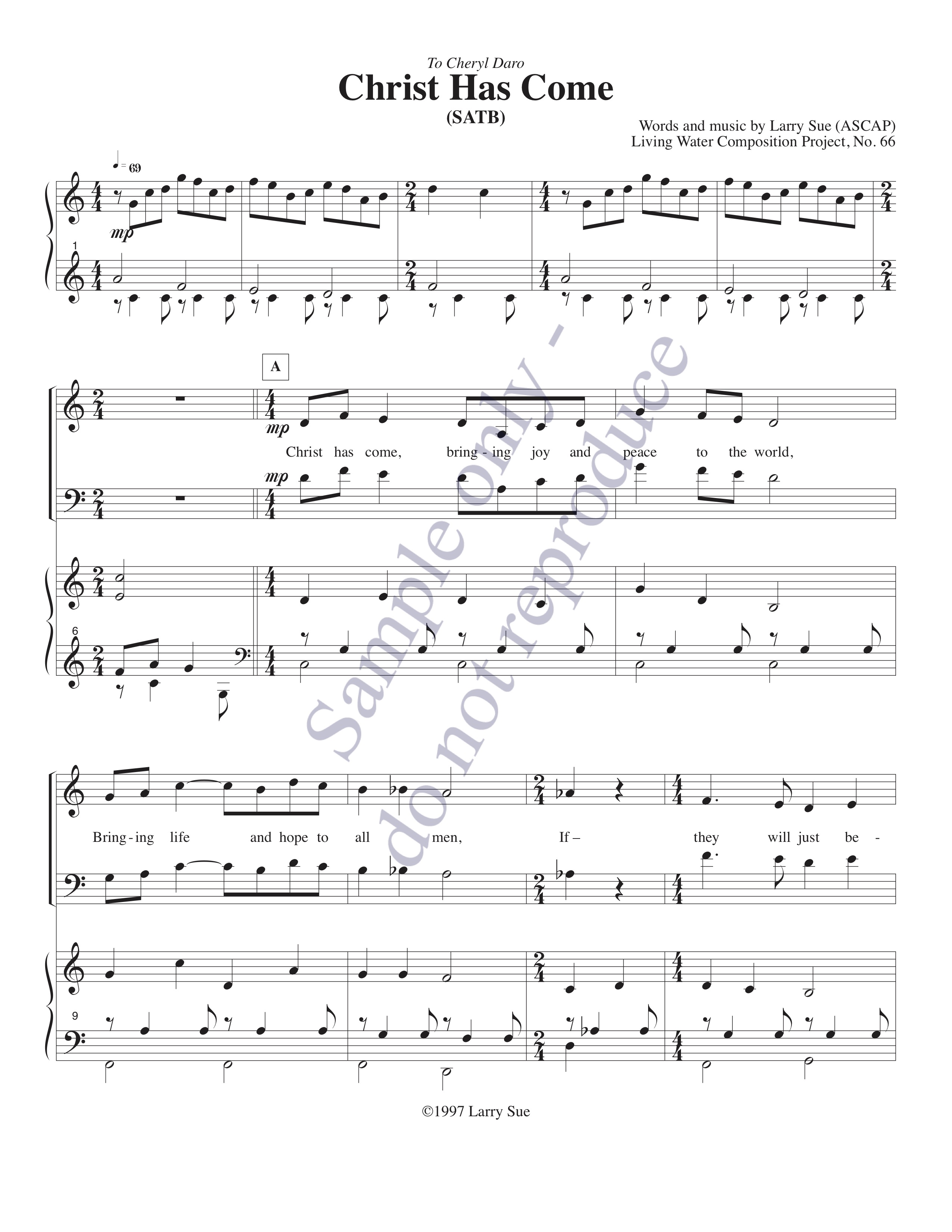

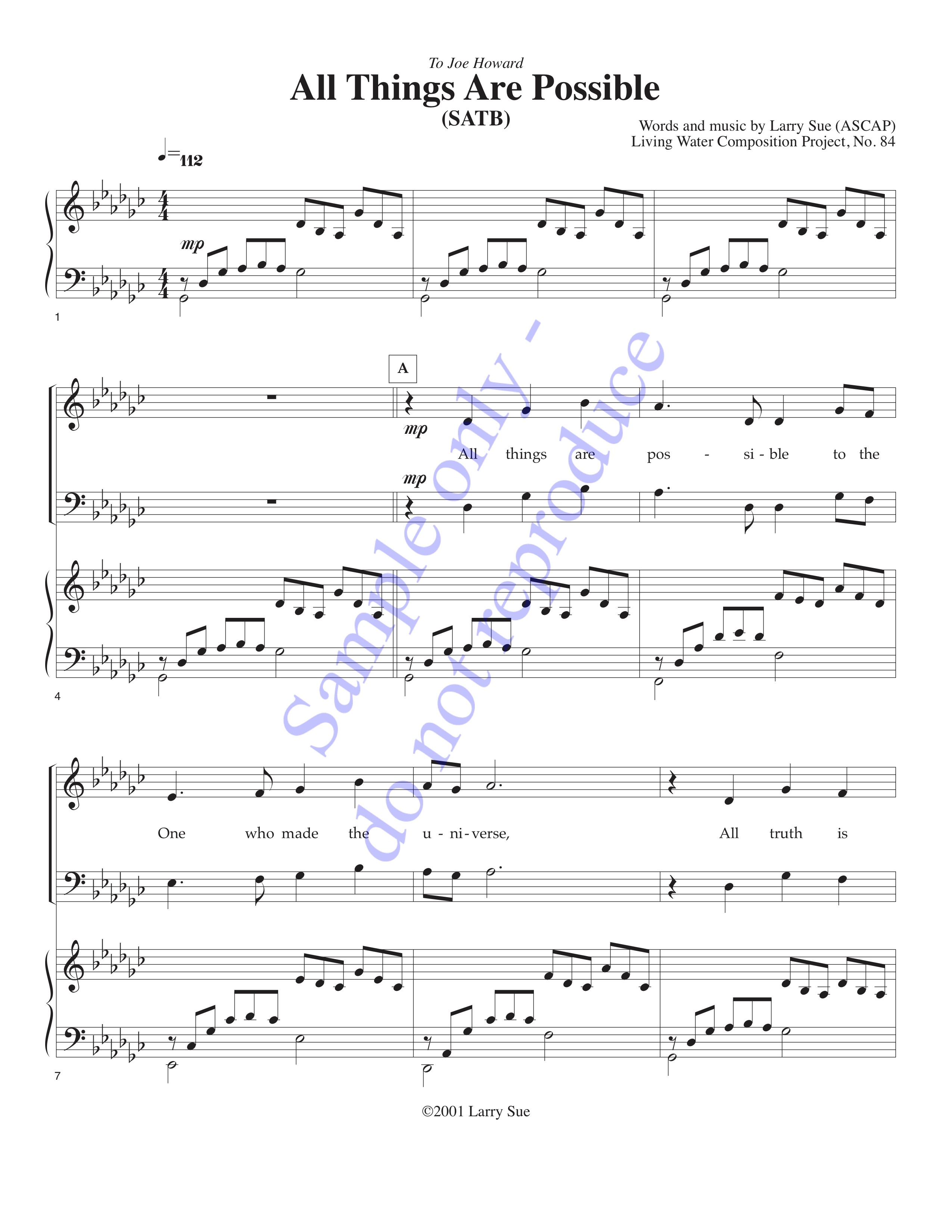

The following is from a series of articles I wrote for Living Water, the choir I directed at Valley Church (Cupertino, CA) from 1987-2003, and at First Presbyterian Church (Mountain View, CA) from 2003-2011. While Living Water is no longer in action, the ideas I had the opportunity to present are just as valid now as then.

Choral diction has been one of my personal emphases ever since I started singing in the choir at my church back in Oakland, California. After joining the choir, it didn’t take long to develop a fascination with the way lyrics and music interact; from there it was a short step to understanding the importance of making the message of the music clear to the listener.

When I became the choir director at another church later, I decided to provide that information to my singers, and so gave them a writeup on the principles of diction as I perceived them. I later refined these as I wrote letters to Living Water one year; these are the diction excerpts from those letters.

Bear in mind that there are various schools of thought on just how choral diction should be taught and executed, and that each of those schools therefore also has its own particular strengths and weaknesses. My way of thinking is to communicate the message, even if the minor sacrifice of lessening the stylistic impact is required. My reason for this is found in I Corinthians 14:7-12 (and, yes, I know the context is about spiritual gifts, not choir – but the principle of communication for edification is identical).

For the informational part of the next bunch of letters, I’d like to share what I’ve learned about choral diction. We’ve been looking at this during rehearsal, so this is an opportunity to reinforce what we’re learning. To start, choral diction is simply the way in which we pronounce our words as we sing. The basis of diction, of course, is found in spoken language which, for our purposes, will be assumed to be English. The reason for this assumption is that different languages have a variety of sounds, and so I want to restrict our initial foray into the subject to the phonemes we use most often. Other languages have non-English sounds: I’m told that Arabic has a hard H and a soft H, and know from familial experience that Chinese has any number of vowels which seem to be halfway between English sounds. Examples closer to home are German, which has the umlaut vowels (å, ë, ö, and ü), and the Scandinavian languages which have still other vowels (Ø, Ä). Still more complicated is Czech, which I’ve heard has sounds which are not taught to students until they are nine or ten years old (such as circumflex-r).

Anyway, there are two basic parts of speech in choral diction: consonants and vowels. The essential concept in precise diction is that vowels define pitch and consonants define rhythm. Consonants such as M and N can also define pitch, but as these applications are infrequent and usually nontextual, I’ll ignore them in my discussion. Vowels require the mouth to be open; consonants require the mouth or throat to be closed (except for H). Vowels are sustainable for virtually any length of time; some consonants are not – it helps to think of vowels being long and consonants being short as long as you realize that there is some blurring of the distinction at some points.

I’ll be considering vowels and consonants separately first, and will plan to finish with some information on how they work together. But that’s enough for now, except to regale you with something dictional I read a long time ago. It seems that a tourist was in London and passed a restaurant. The proprietor had clearly stated his and his staff’s linguistic orientation, for there was a card in the window which said: “English spoken – American understood.” So if you’ll care for the tyres on your lorry, take the lift when possible, avoid undue visitation to pubs, and remember that in Britain they’re called nappies rather than diapers, you indubitably sha’n’t be afoot when the game’s afoot…

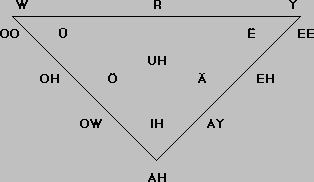

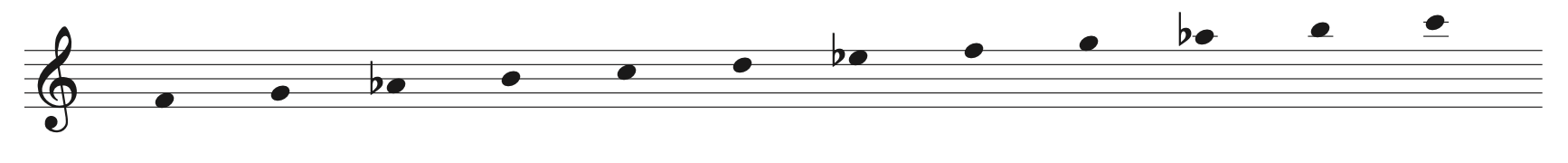

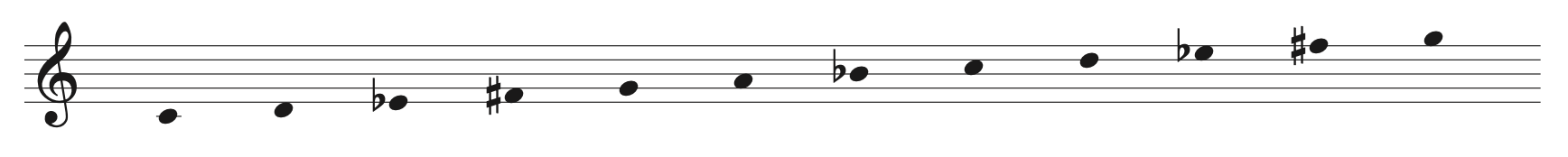

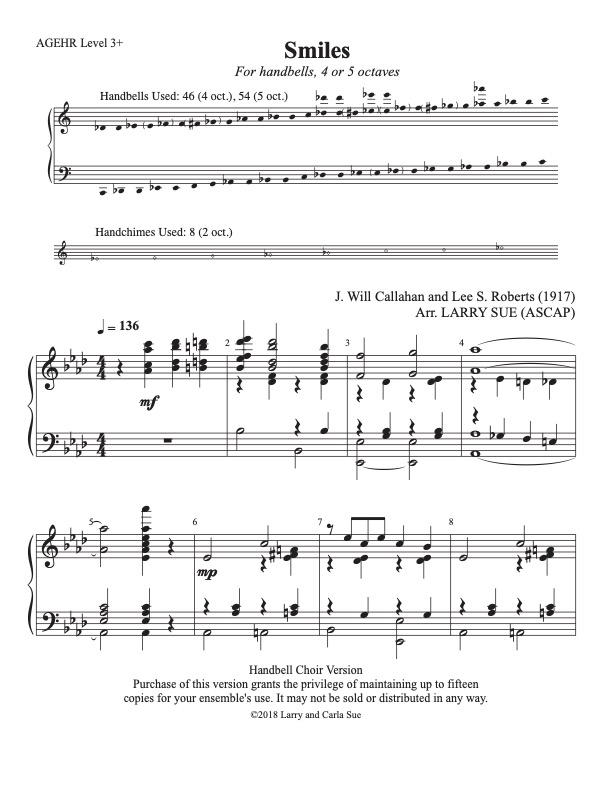

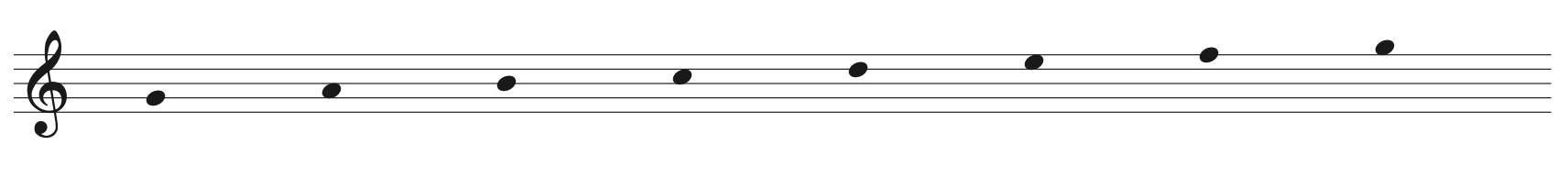

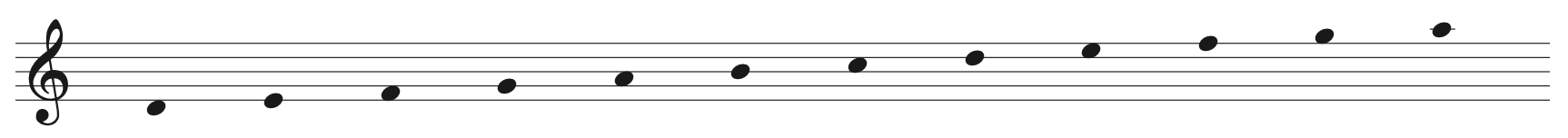

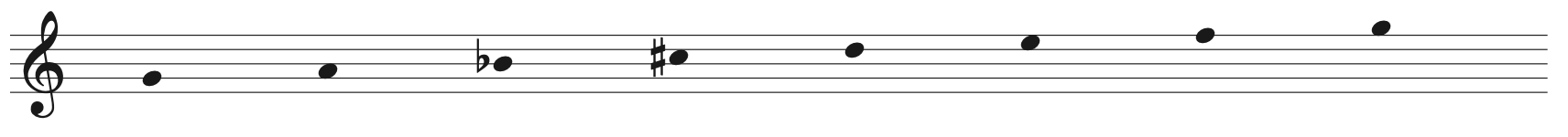

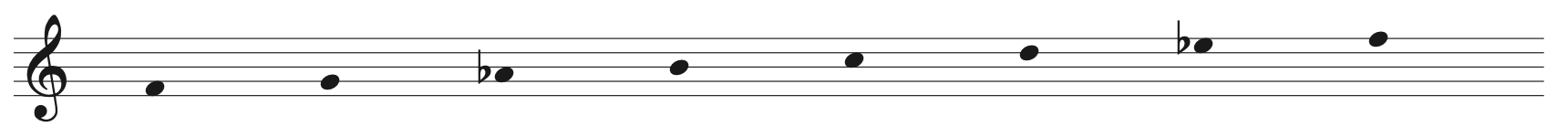

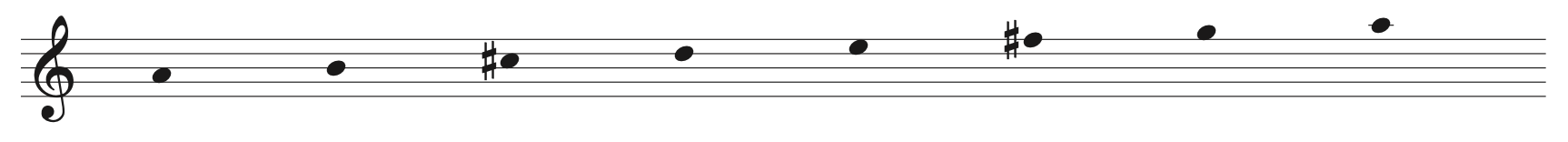

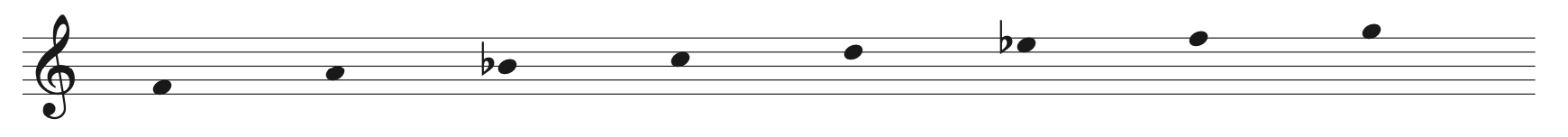

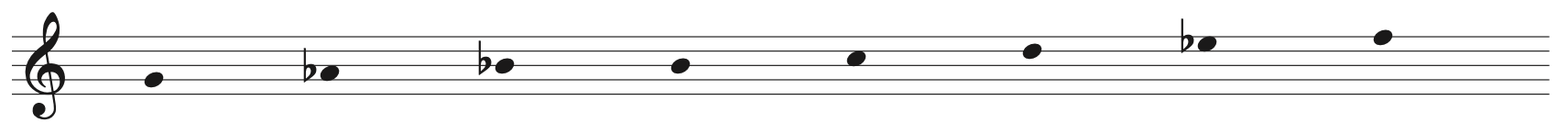

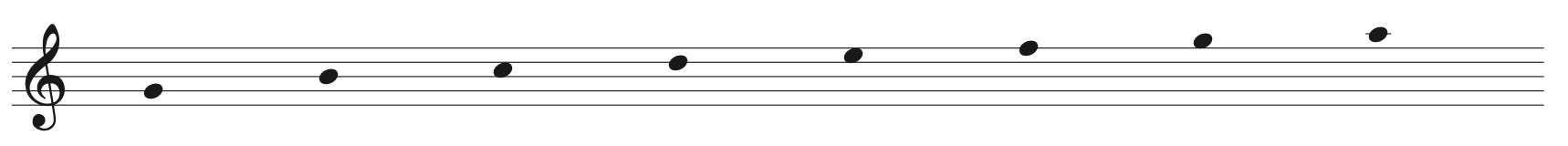

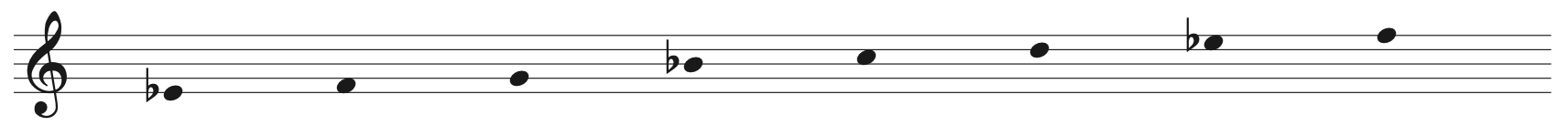

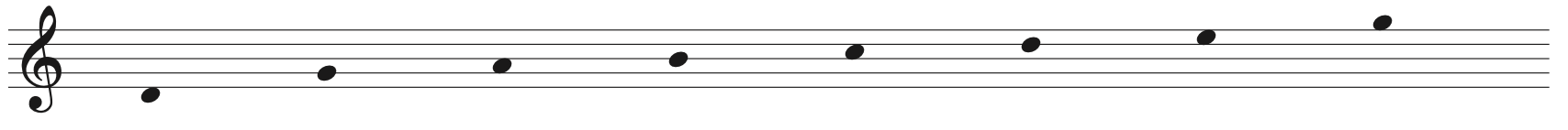

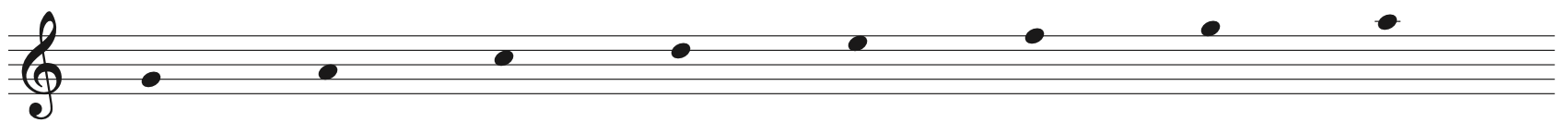

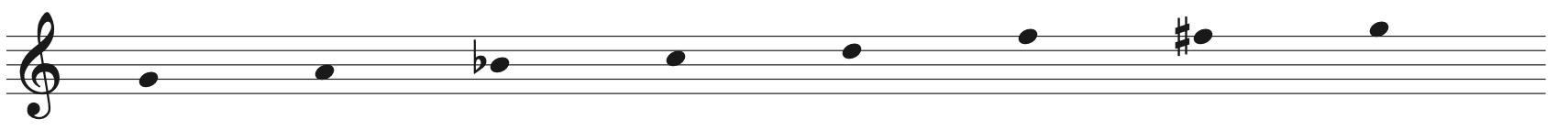

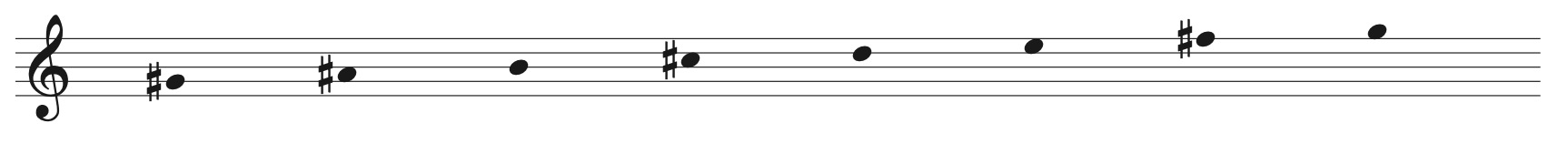

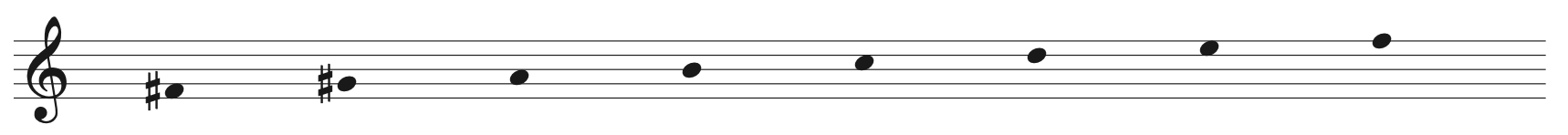

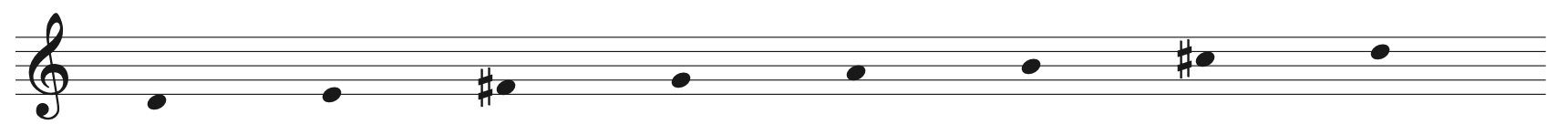

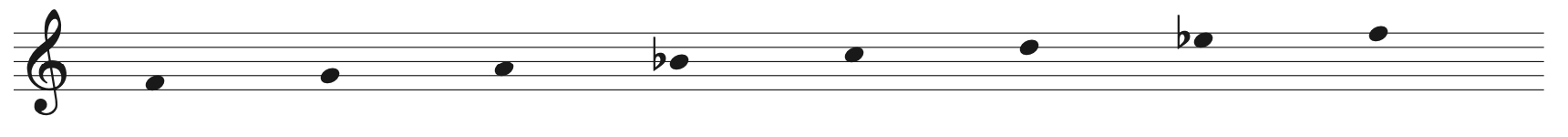

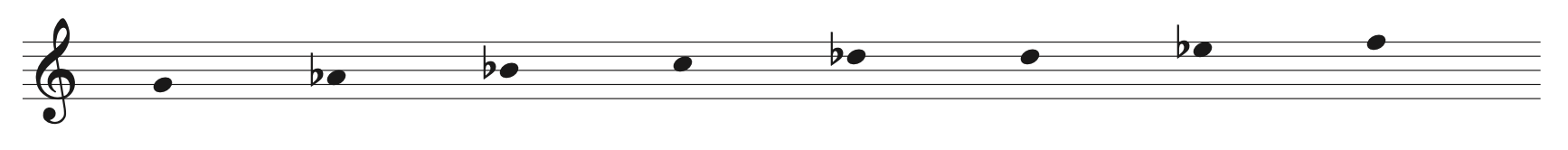

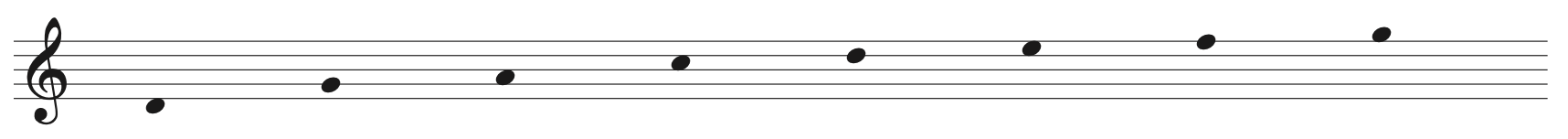

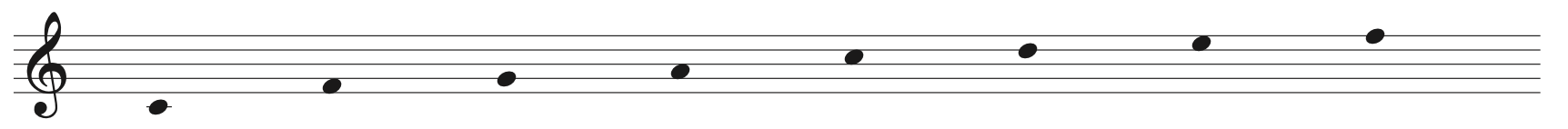

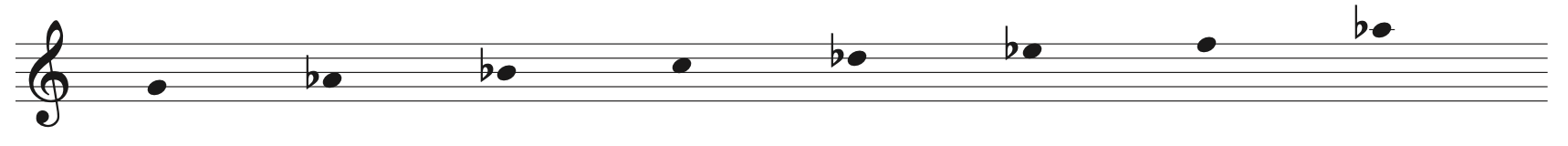

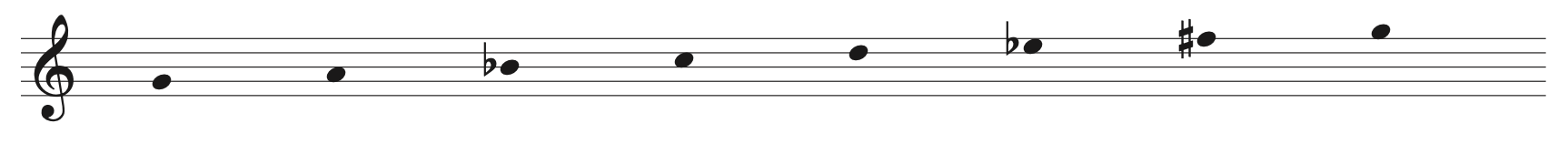

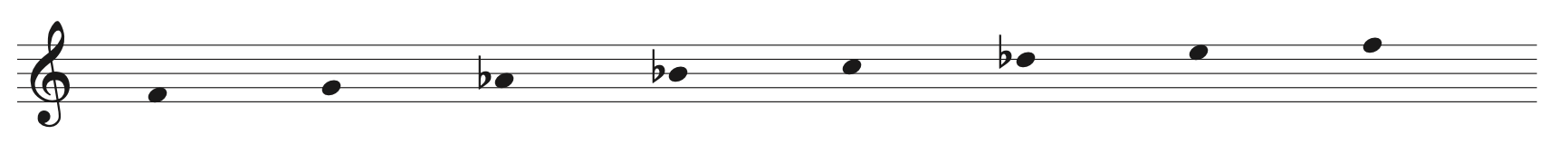

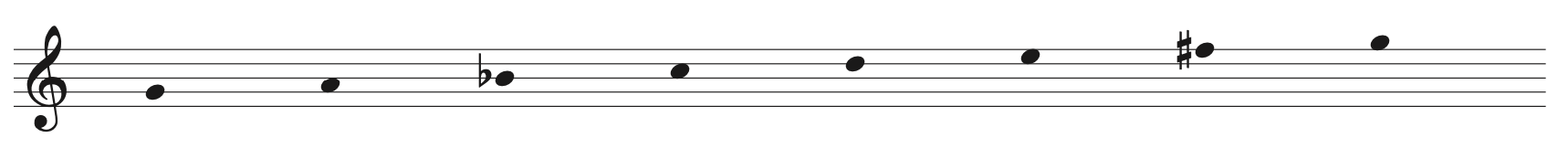

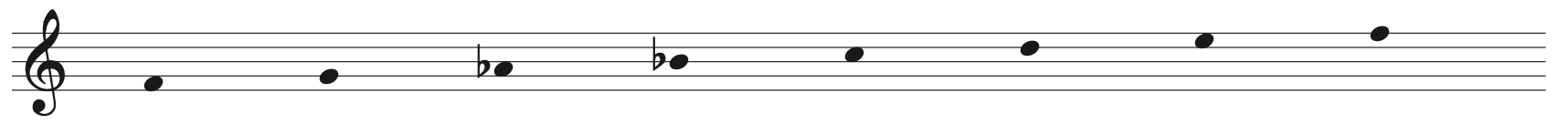

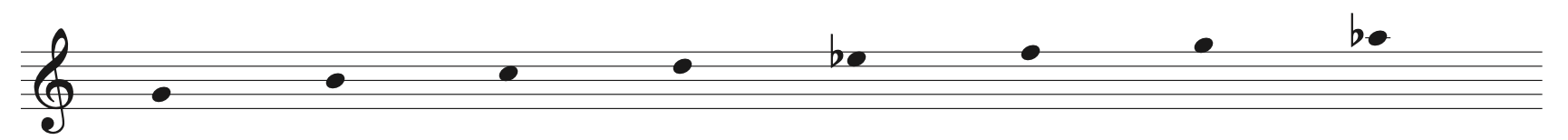

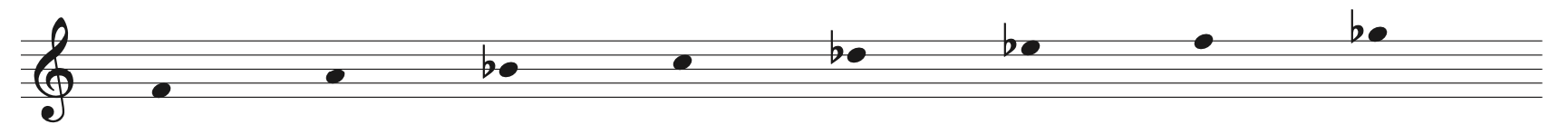

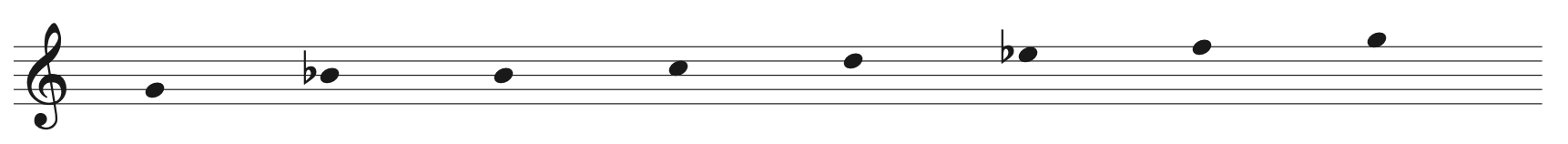

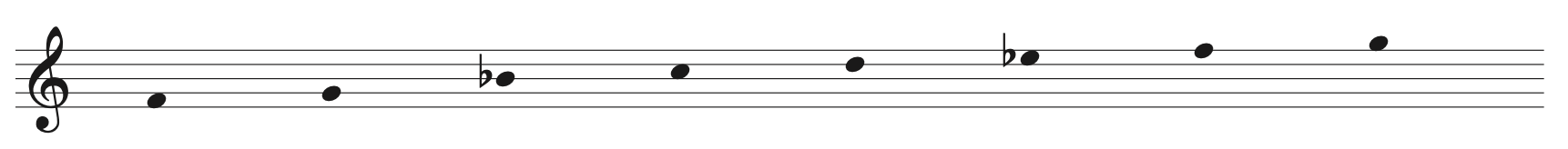

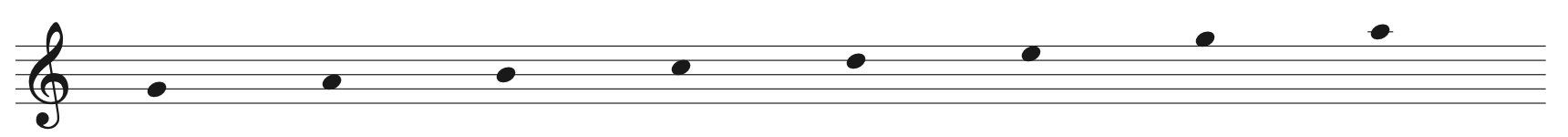

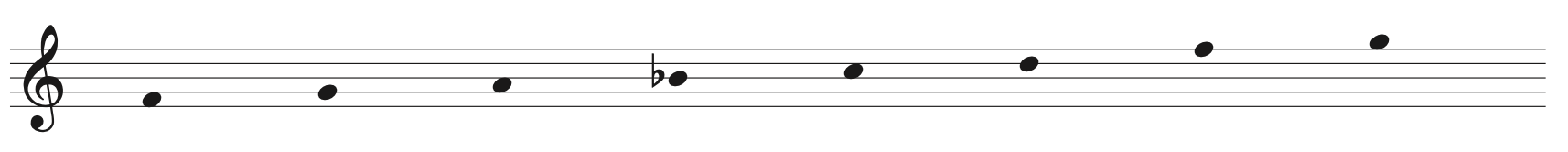

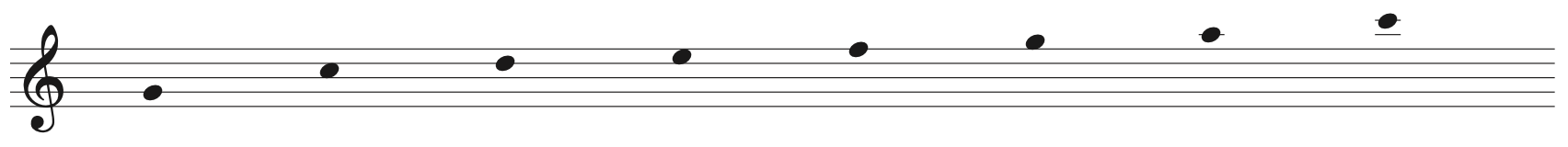

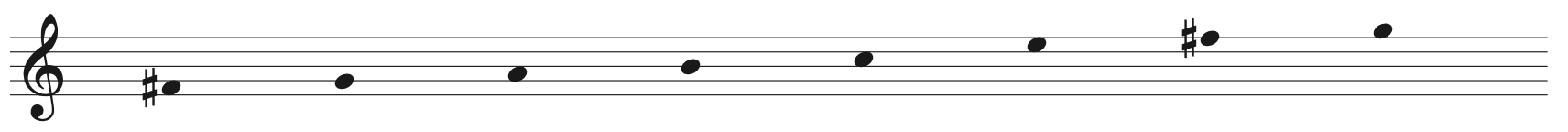

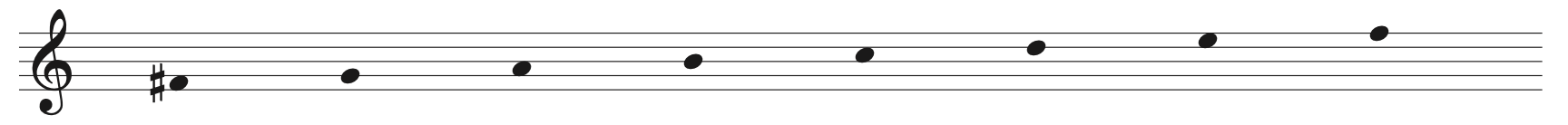

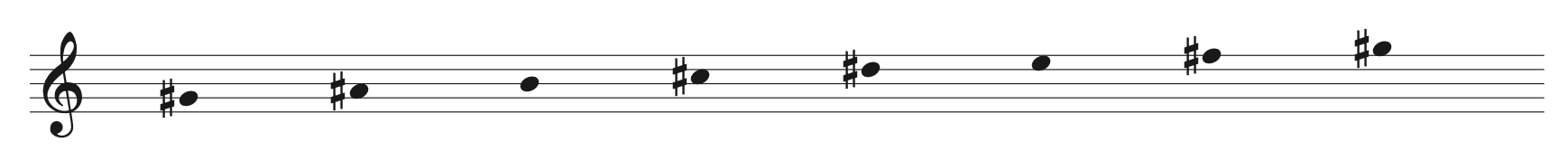

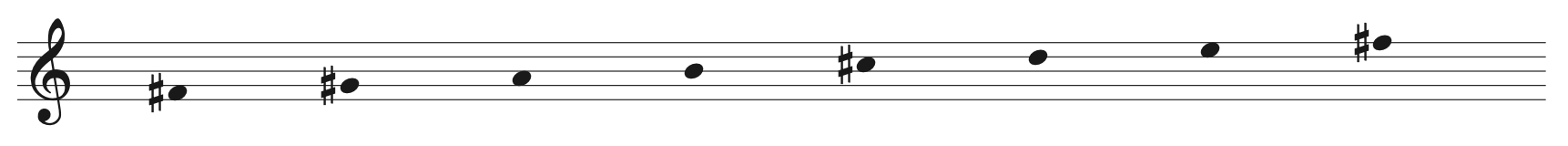

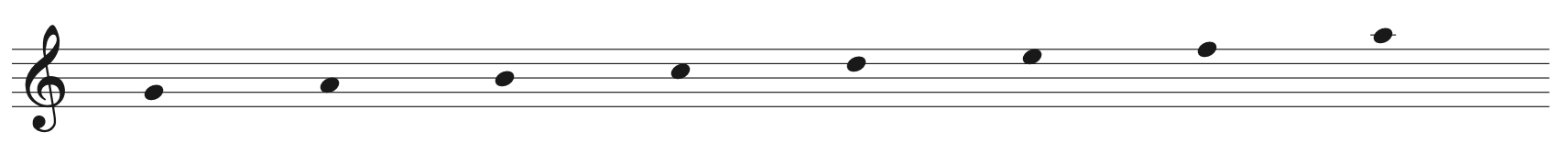

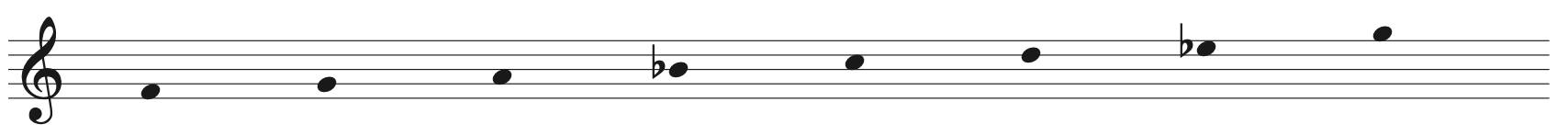

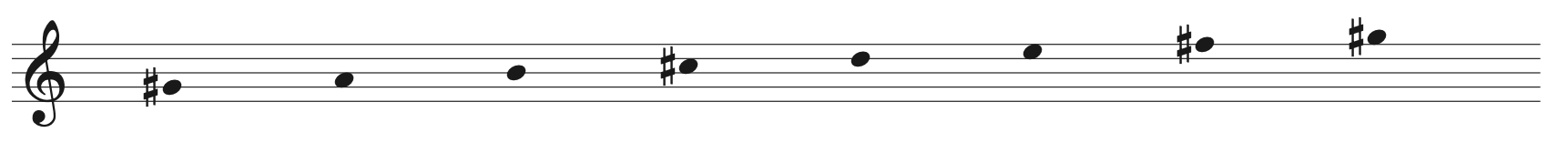

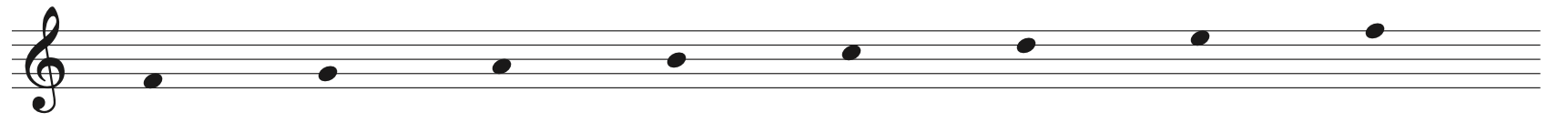

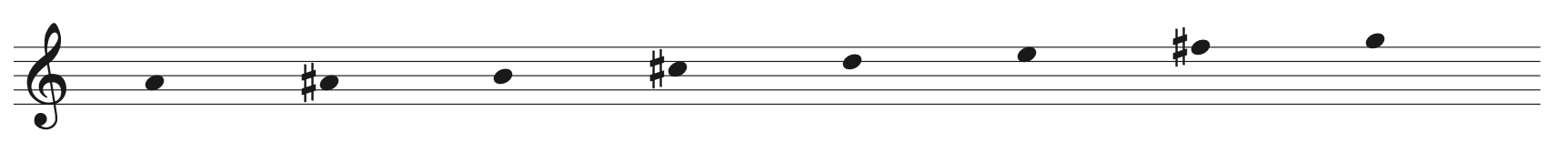

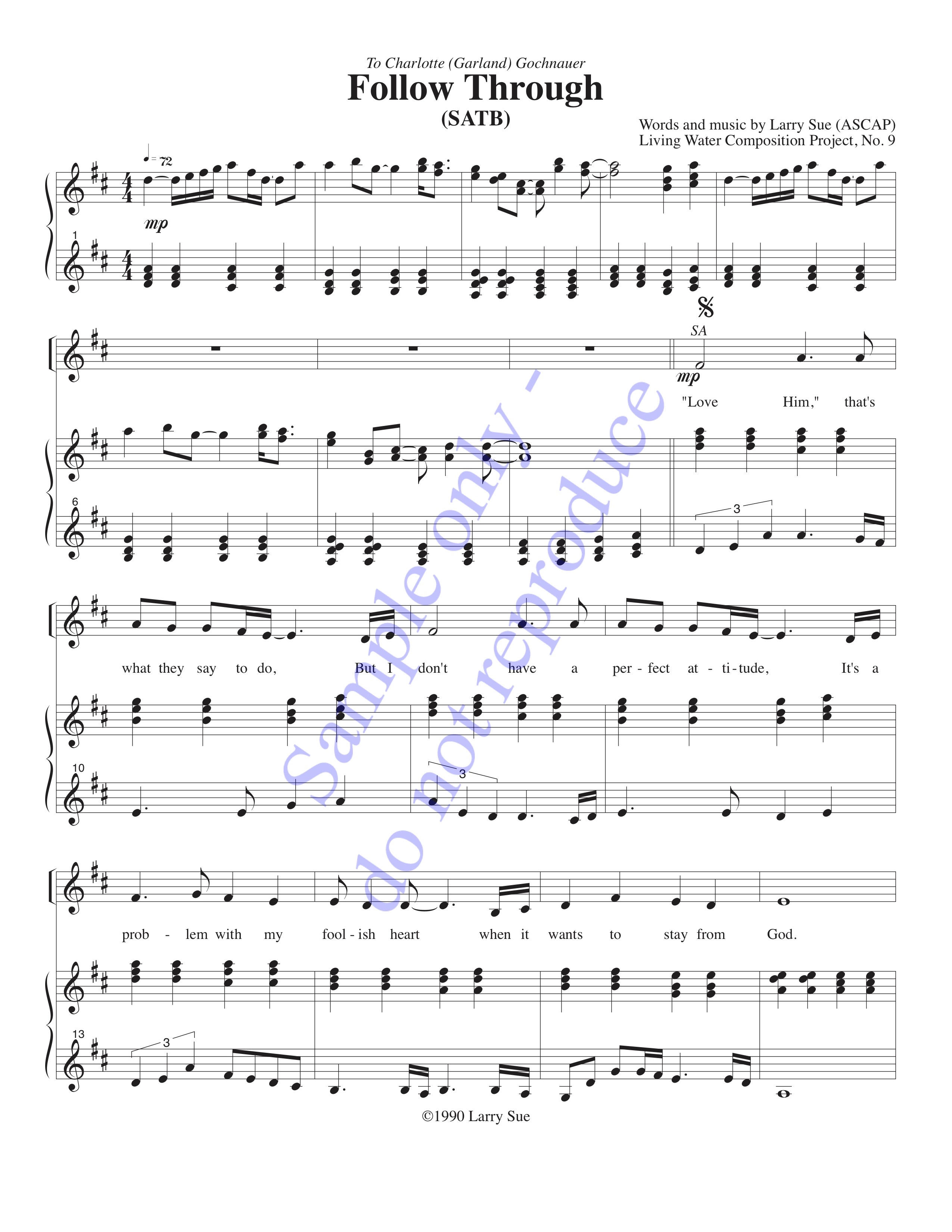

As I wrote last time, the two major types of dictional elements are vowels and consonants. The basic vowel sounds are OO, OH, AW, AH, AY, EH, and EE. Yes, there are other vowels, such as UH, Å, Ë, Ö, and Ü. A friend once showed me a diagram which presents a clear picture of how the vowels are related:

Vowels are the means by which we sing pitches and achieve tone color. You’ll notice that the picture above lists the vowels in phonetic rather than alphabetical order. There are a number of interrelationships which can be drawn from the diagram:

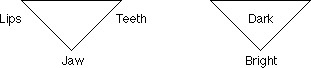

The first small picture shows where the vowels tend to be placed; the other shows color tendencies. The fact that vowels are placed in this arrangement offers a way to achieve vowels modifications (for instance, when your director tells you to sing “G-AW-D” rather than “G-AH-D”). the modifications are therefore based on going from a vowel to an adjacent vowel – it also explains why you can use sounds like OO to modify EE (they’re in the same line)

The first small picture shows where the vowels tend to be placed; the other shows color tendencies. The fact that vowels are placed in this arrangement offers a way to achieve vowels modifications (for instance, when your director tells you to sing “G-AW-D” rather than “G-AH-D”). the modifications are therefore based on going from a vowel to an adjacent vowel – it also explains why you can use sounds like OO to modify EE (they’re in the same line)

What are R, W, and Y doing at the top of the diagram? Although we are taught to treat them as consonants in general terms, there are many words in which they can be treated as vowels: CARD, SNOW, SAY. They’re at what I tentatively call the “choke point” of the vowels directly under them, just say one of those vowels and begin to close your jaw ever-so-slowly and you’ll see what I mean (W and Y are actually “diphthongs,” but this is a convenience for the sake of explanation). They tend to be less than fully functional vowels because they don’t have as clear a sound – which, I think, is why many directors have their choirs eliminate all Rs from their vocal texts. There are, however, stylistic considerations which may encourage use of one of these as a sustained vowel – as a general rule, country music uses a lot more R than classical music does.

The application of this to choral singing is that the types of vowels you use determine the type of tone you achieve. Dark vowels tend to produce the sounds you’d want to hear in the church at Mission Santa Clara (it’s a historically wonderful place to visit); bright vowels are more what you’ll hear in a contemporary artist’s concert.

The concept of a “center vowel” is helpful in terms of producing a consistent sound type. It seems that different vowels work best for different people, so you’ll have to play with your own voice to determine just where the most comfortable center vowel is. I’d recommend starting from AH and working to either side no farther than one or two vowels. it turns out that being able to adjust your center vowel can also make it easier to change styles: For classical styles, I find myself centering somewhere between AH and OH, while for contemporary styles, I gravitate toward a point between AH and AY.

Next time: diphthongs (which are not beach sandals from an obscure island paradise…).

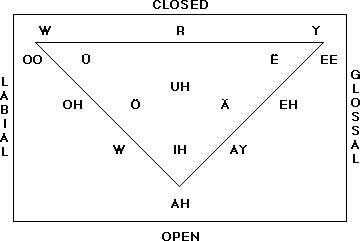

I was looking through some really old stuff I wrote a few years back and found the original-second-generation vowel chart. The labels one the edges of the box describe the vowels in physiological terms. “Closed” and “open” refer to whether your mouth tends to be closed or open; “labial” indicates vowels formed primarily by the lips, and “glossal” indicates vowels formed primarily by the tongue.

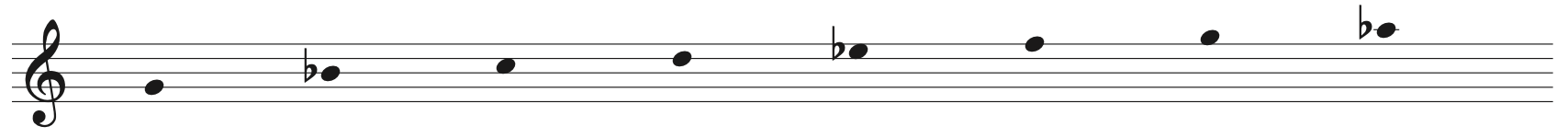

Put on your diphthongs and let’s go to the beach! As I promised last letter, this is the dictional topic of the moment. Diphthongs (from “di” = two, “phthongos” = voice) are vowels or vowel combinations which are composites of one or more simple vowels, such as:

Put on your diphthongs and let’s go to the beach! As I promised last letter, this is the dictional topic of the moment. Diphthongs (from “di” = two, “phthongos” = voice) are vowels or vowel combinations which are composites of one or more simple vowels, such as:

- I (long) = AH + EE

- EW = EE + OO

- OW/AU = AH + OO

- OY = OH + EE

If you allow W and Y to be vowels, words such as WE, YOU, YAW, and WAY become diphthongs. If you’re willing to consider R as a vowel, OR, ARE, and EAR are diphthongs and WERE, YOUR, and WAR are not merely diphthongs but “triphthongs.”

Diphthongs are important to choral diction not only because they are integral parts of the words which contain them but because they require special treatment when enunciated. The traditional approach is to sing only the first vowel sound in the diphthong (e.g. OH in “OY,” or “EE” in “EW”), switching through the other vowel sounds at the last possible instant when transitioning to the next syllable. Example: in rather exaggerated form, “few toys” would be sung:

FEE——–ooTOH——-eeS

Next time, we move on to consonants.

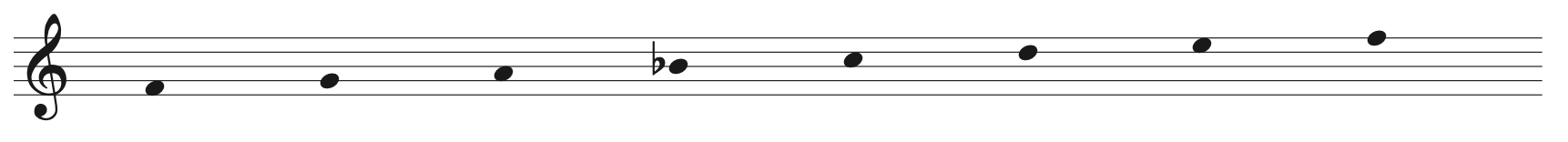

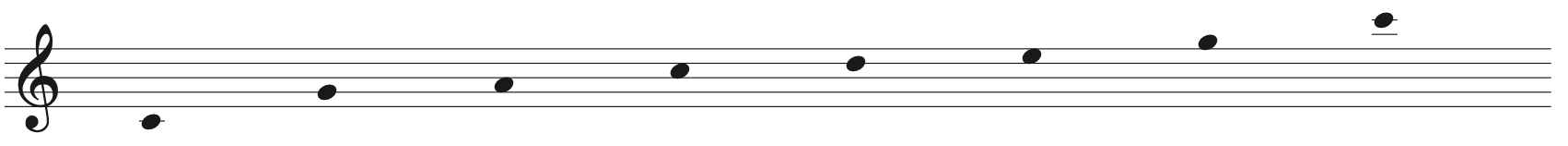

The diction workshop continues into consonants. If you’ll remember, vowels define the pitch and part of the style in singing. Consonants are complementary to vowels in that they define rhythm. In some music, particularly the more avant-garde stuff, there is also the usage of some consonants to define pitch too (I might actually remember to discuss this later).

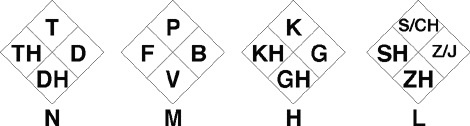

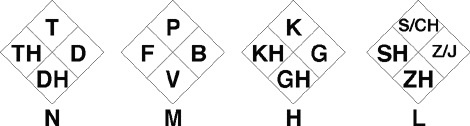

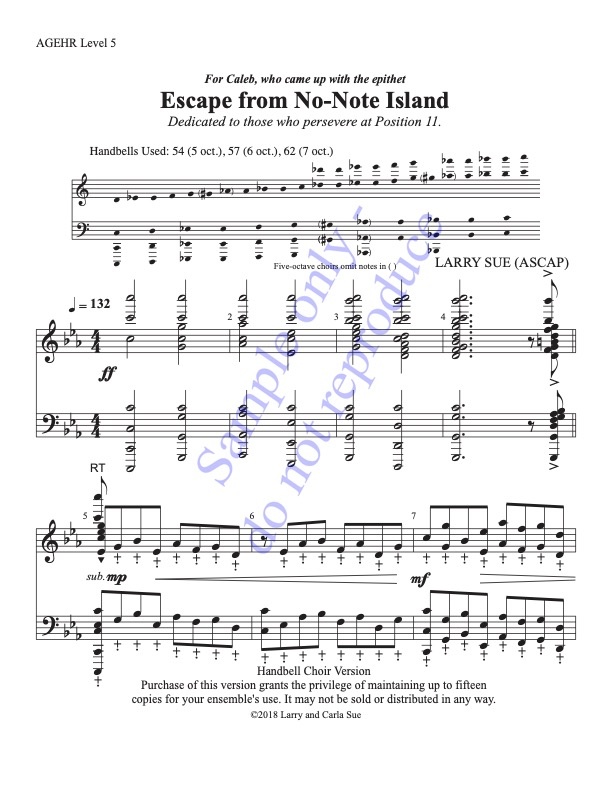

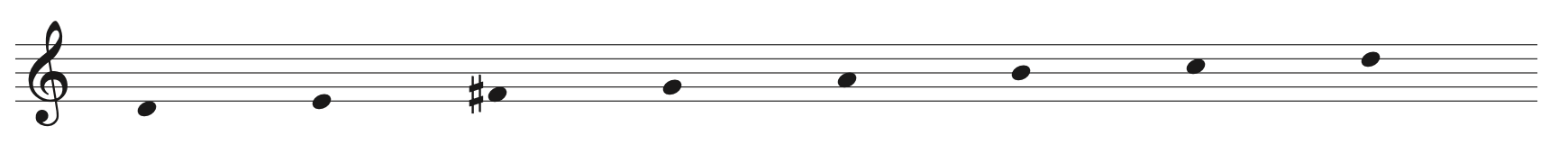

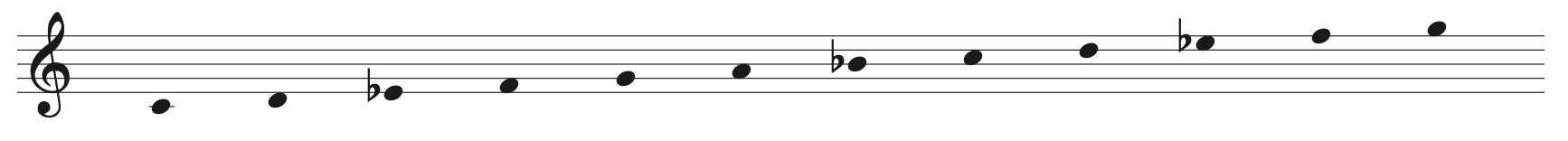

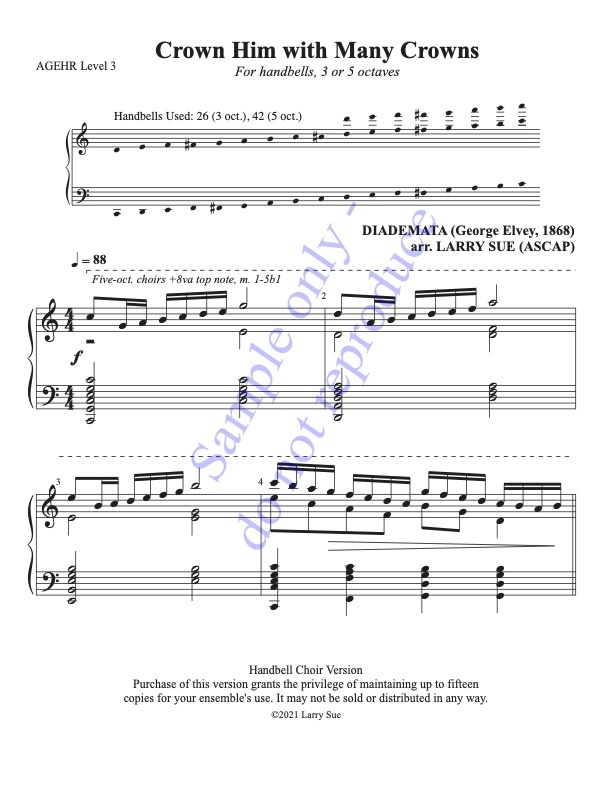

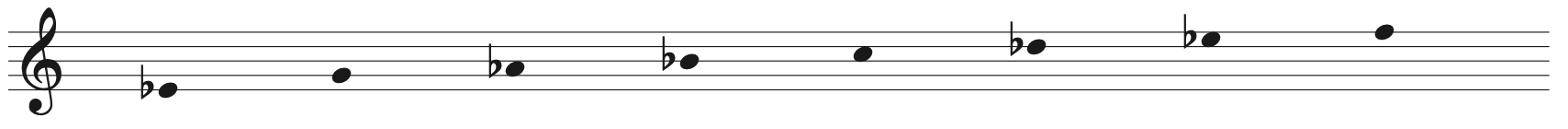

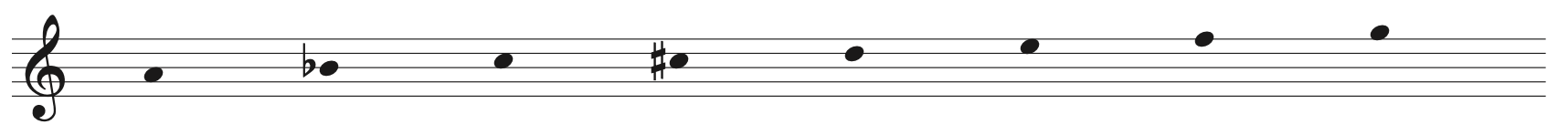

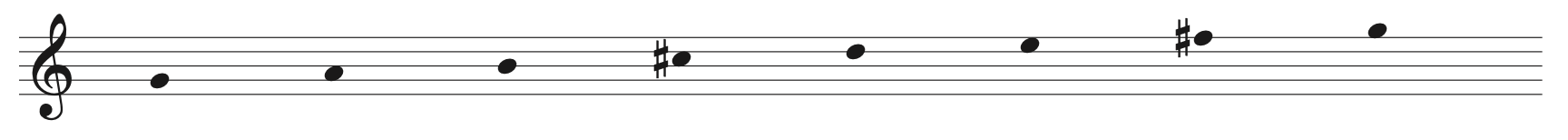

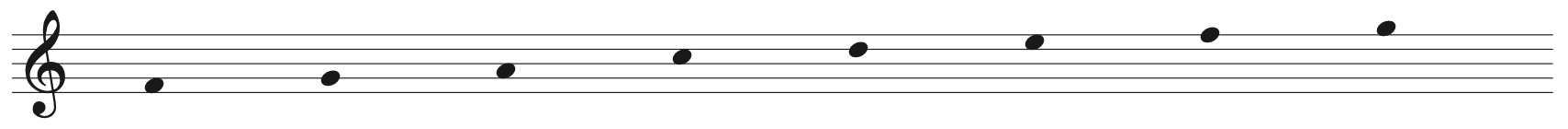

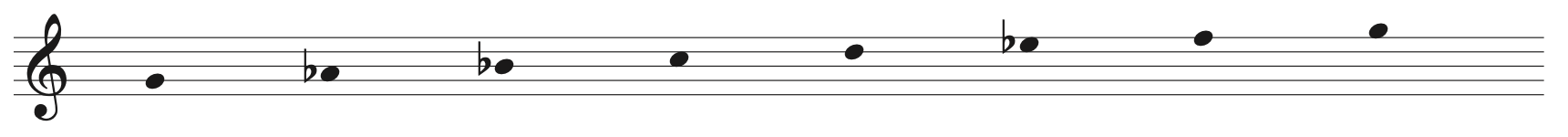

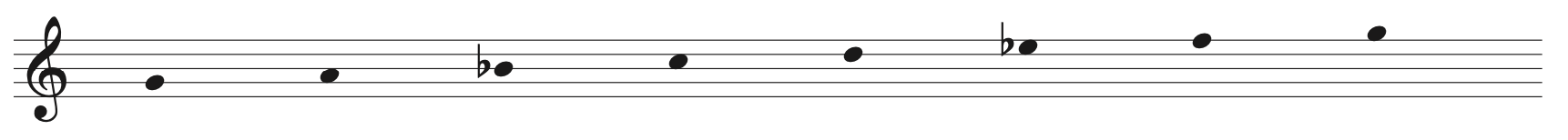

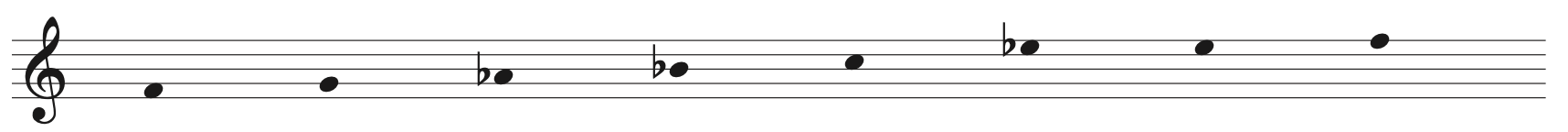

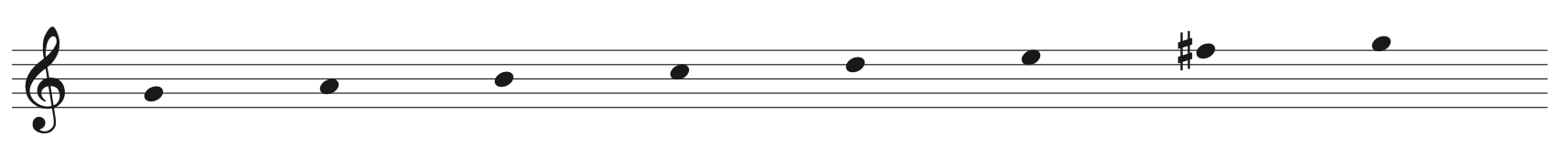

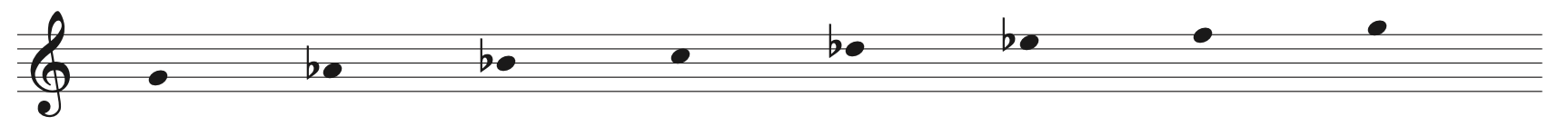

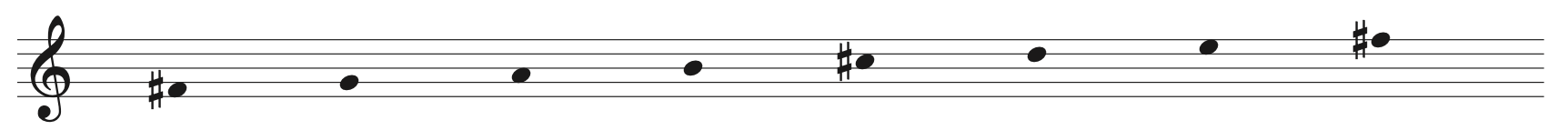

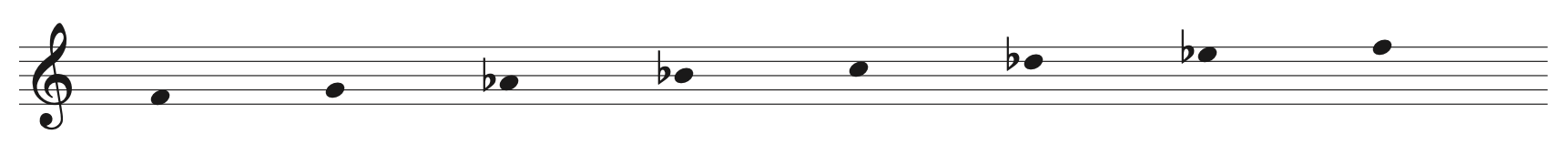

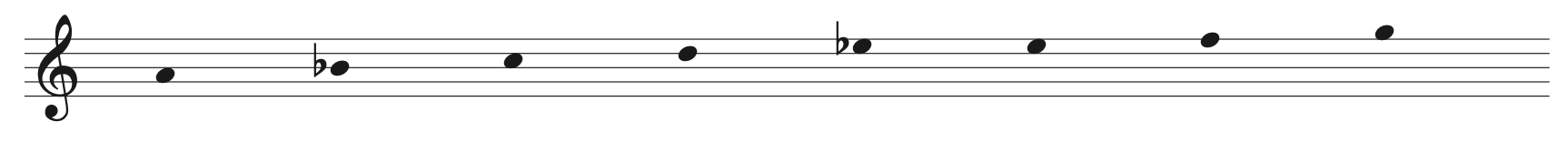

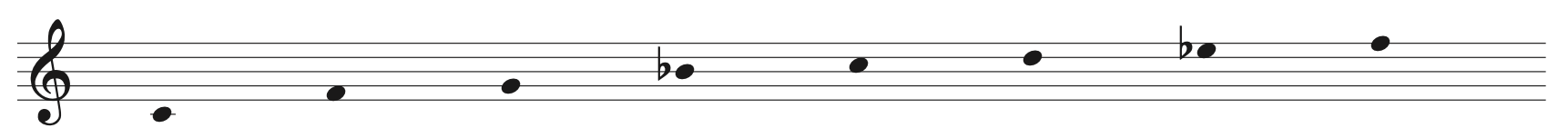

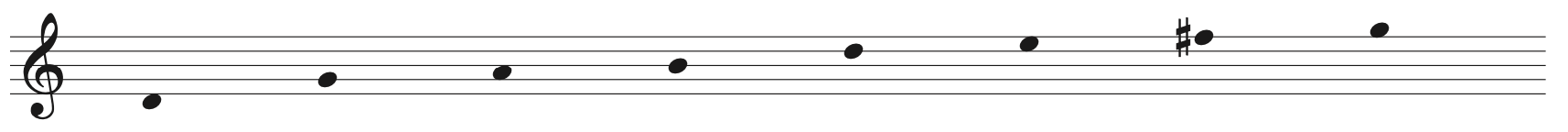

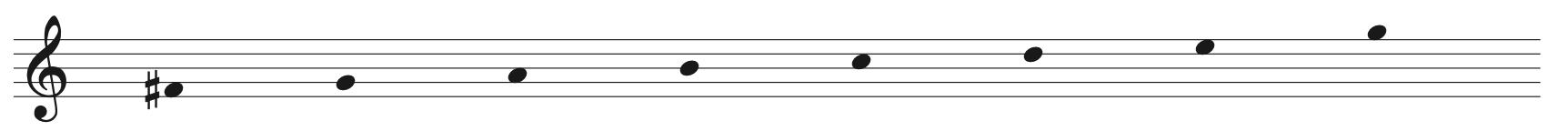

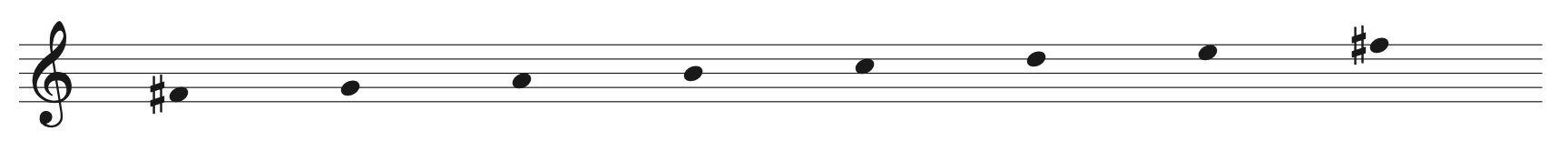

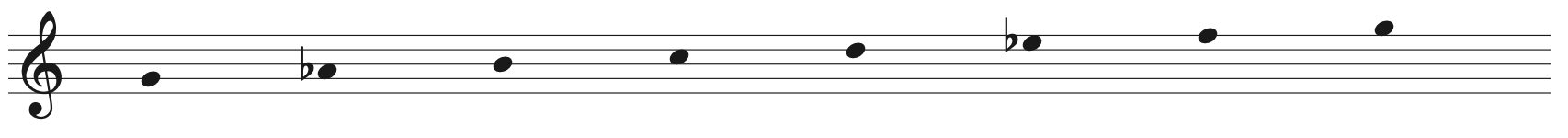

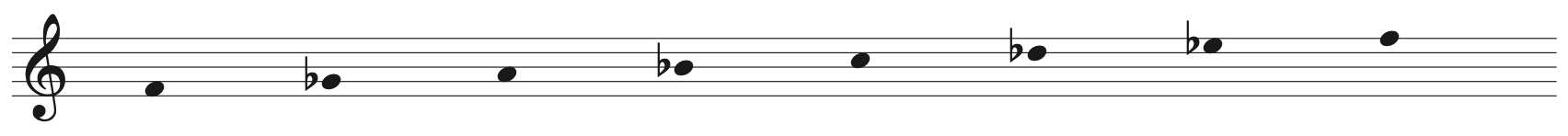

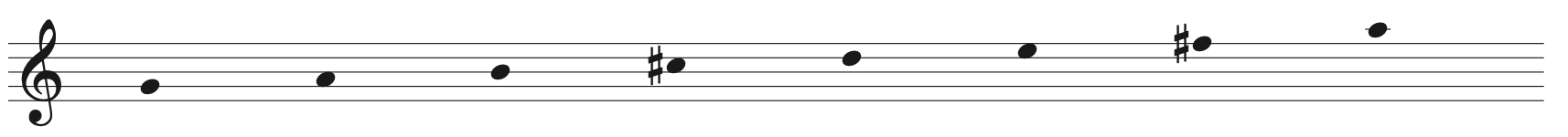

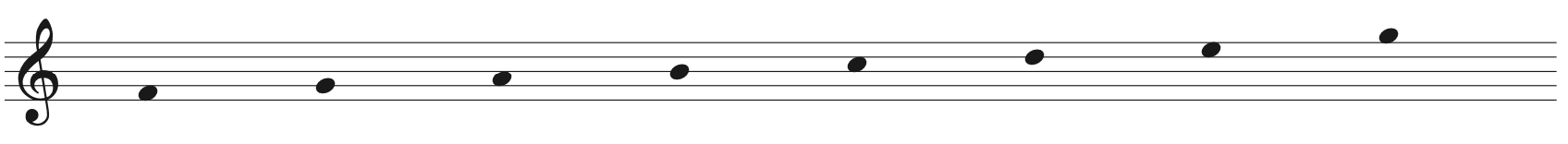

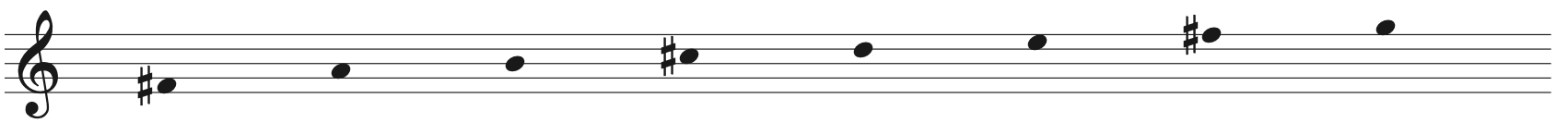

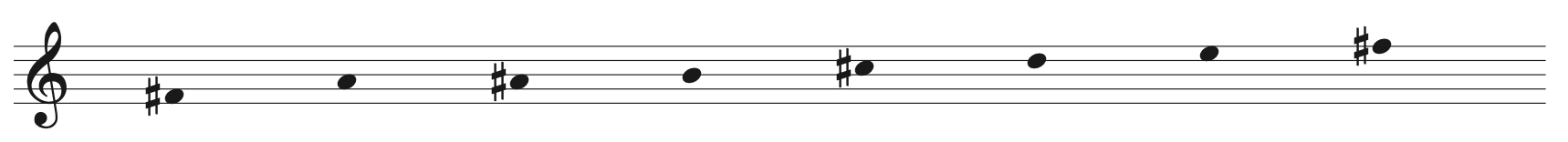

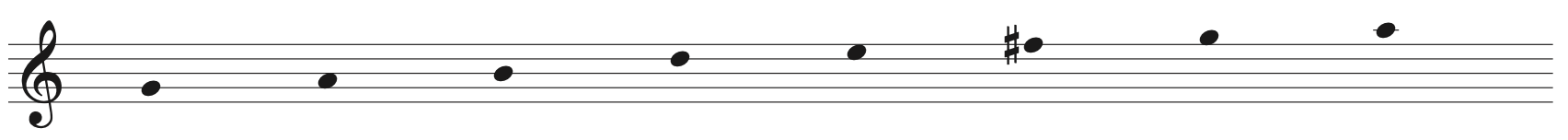

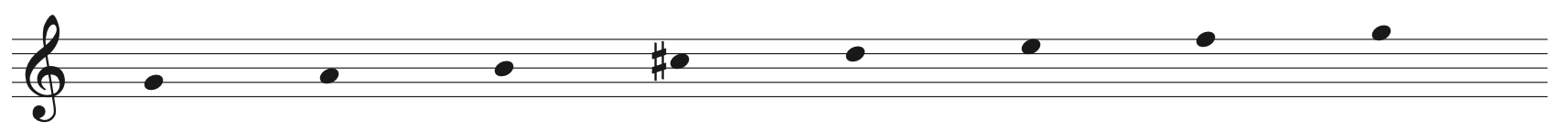

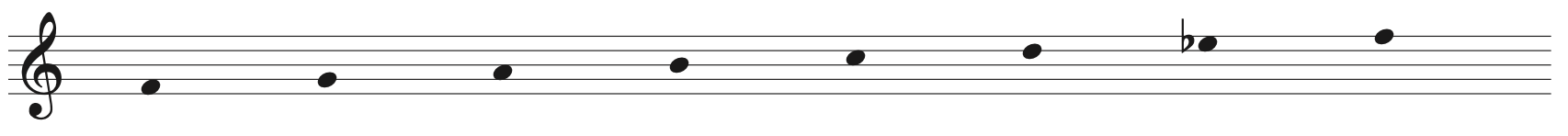

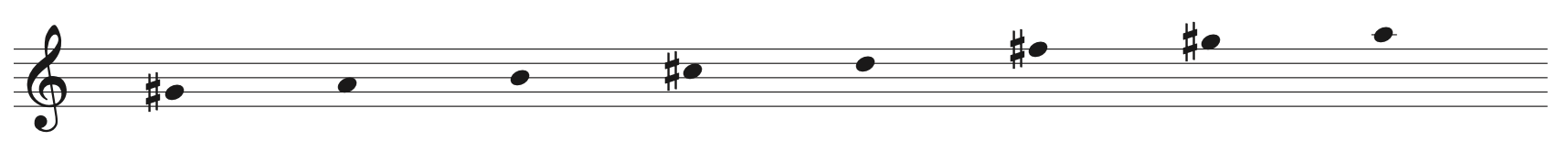

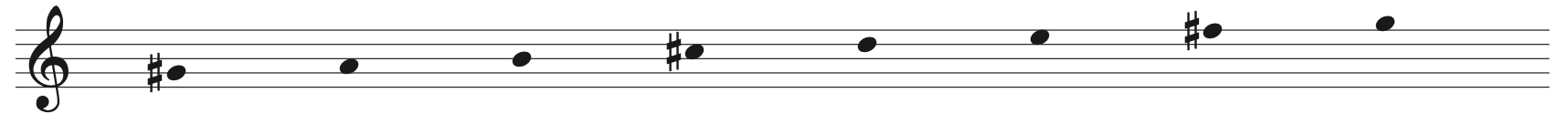

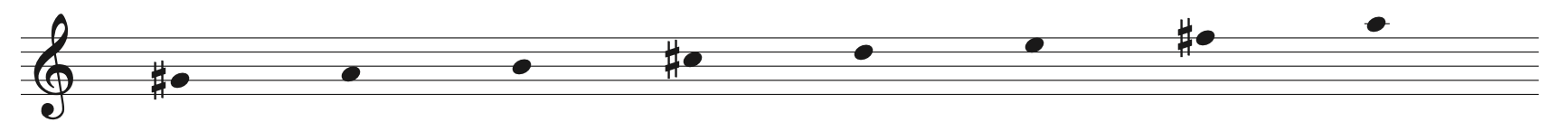

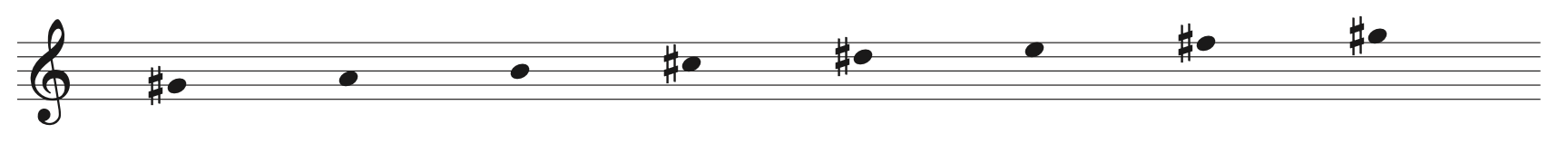

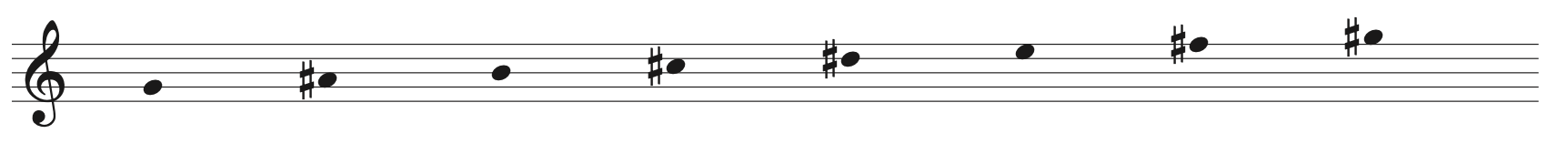

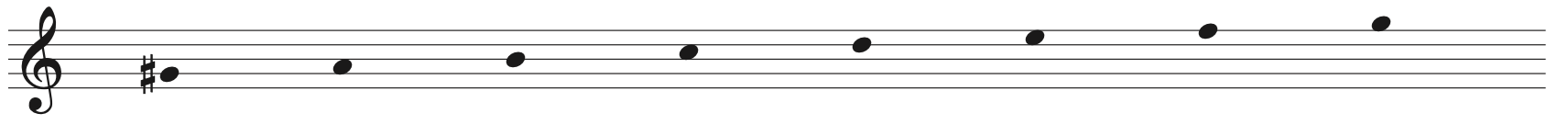

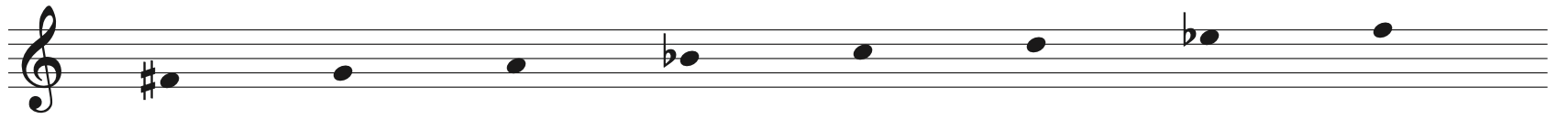

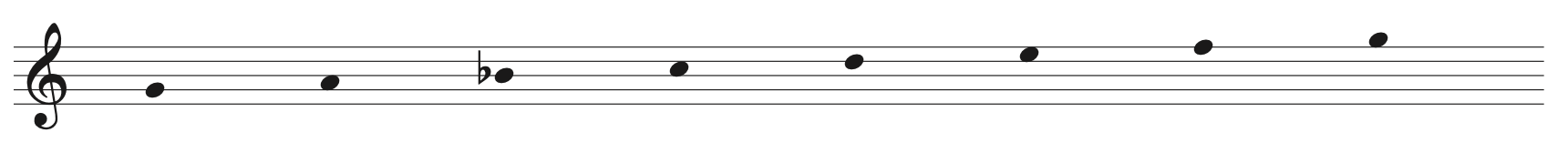

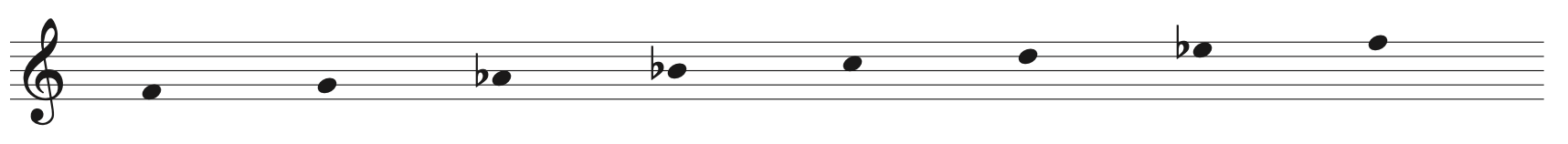

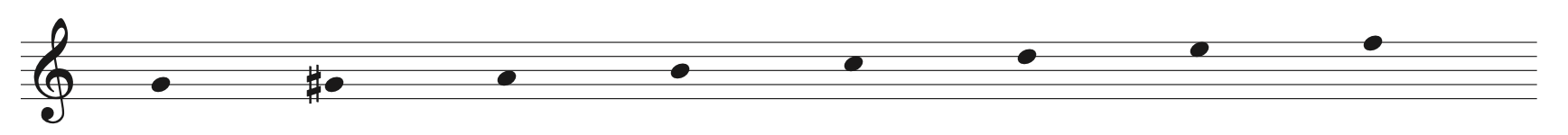

Here’s a reasonably clear way of classifying consonants:

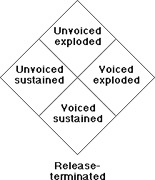

Each of the four “diamond charts” above describes a family of consonants. The consonants in each family all have roughly the same dictional configuration (pronounce them and you’ll see what I mean). Here’s the key to each family chart:

“Voiced” refers to consonants which have pitch (i.e. are pronounced by including the vocal cords in the action).

“Voiced” refers to consonants which have pitch (i.e. are pronounced by including the vocal cords in the action).

“Unvoiced” consonants do not use the vocal cords.

“Sustained” consonants have a controlled duration.

“Exploded” consonants are terminated quickly.

“Release-terminated” consonants have duration, are initiated with a partially-closed air path (e.g. by closing the lips or teeth), and are terminated by open the air path. “H” is a bit of an exception here, but the idea still works pretty well.

Incidentally: W, R, and Y are pathological in the sense that they aren’t really consonants (and actually, in a sense, not really vowels either).

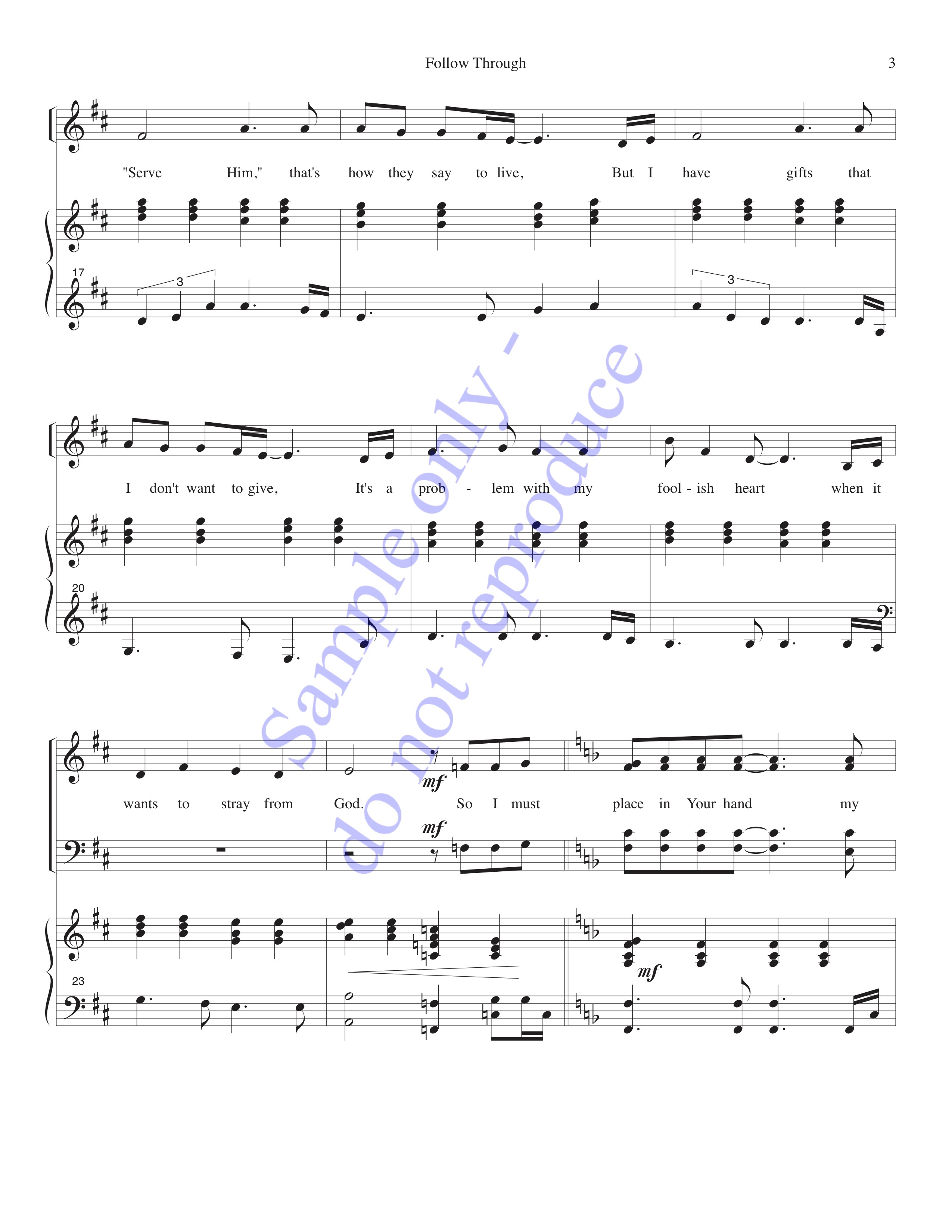

Here, again, is the consonant chart:

I use this table as a guide to how I pronounce the words I sing. The reason for pursuing the topic to such excruciatingly fine detail is that of all the aspects of vocal music, the most important is that of communicating the message of the song to the listener. If you will, it’s an act of love for those in the congregation which is in accordance with I Corinthians 13:1-3 (please read these verses!). A corollary to this passage might be “If I sing the greatest song of all time to the most spiritually appreciative congregation of all time, but do not love them enough to make the message of the song clear to them, I cannot minister to them and they cannot be blessed by the talent that God has given me.” Think about this!

I use this table as a guide to how I pronounce the words I sing. The reason for pursuing the topic to such excruciatingly fine detail is that of all the aspects of vocal music, the most important is that of communicating the message of the song to the listener. If you will, it’s an act of love for those in the congregation which is in accordance with I Corinthians 13:1-3 (please read these verses!). A corollary to this passage might be “If I sing the greatest song of all time to the most spiritually appreciative congregation of all time, but do not love them enough to make the message of the song clear to them, I cannot minister to them and they cannot be blessed by the talent that God has given me.” Think about this!

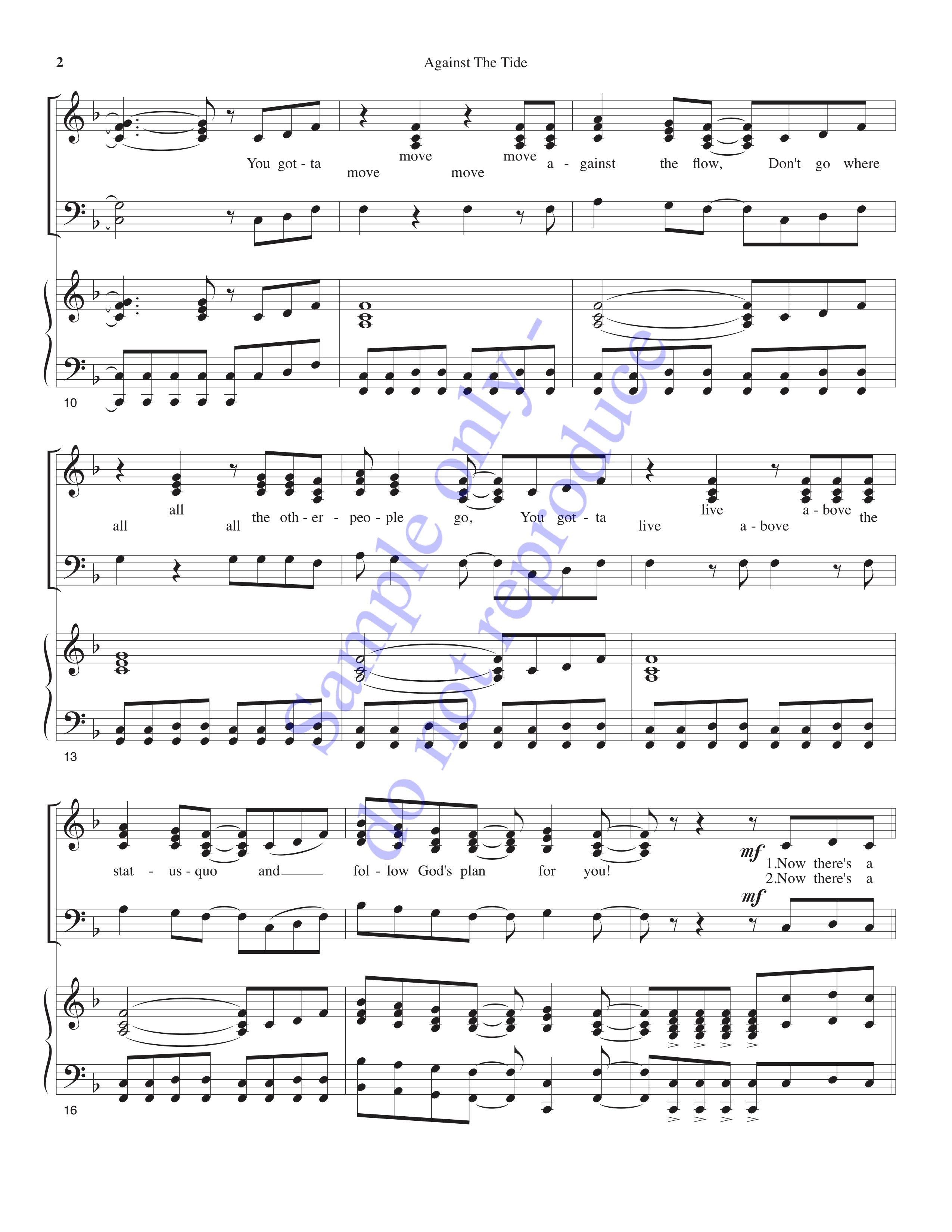

The primary use that of the consonant chart is to engineer the distinction between consonants. It turns out that consonants in the horizontally adjacent boxes have a tendency to blur into each other; an example from a couple of years ago occurred during the summer of 1989 when we sang “Live It To The Max.” Those of you who were there will remember that we were working on the title song when a dictional problem surfaced: the “T” in “It” was becoming a “D” because of the style of the piece. This resulted in “LIVID to the Max” (can you imagine an angry Hawaiian?).

The simplistic solution (so that I can break this off until the next letter) is to learn to pronounce each consonant purely as indicated in the table (this essentially is the classical method of consonantal diction). An experiment: Say this sentence as if during a conversation:

The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

Now repeat it very slowly, taking care to pronounce each consonant precisely as it appears in the table (i.e. a la classical diction). Then continue to repeat it more and more quickly until you’re back to conversational speed. You should notice a marked difference in the way the sentence sounds and feels, particularly in how you’re pronouncing the voiceless and sibilant consonants. If you have the inclination, try this with other sentences, especially tongue twisters (e.g. “She sells sea shells by the seashore,” “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers,” and “The sixth sheik’s sick sheep seeks the sick sheik’s sixth sheep”).

Next time: Digraphs, trigraphs, and interaction of vowels and consonants.

We start with a couple of definitions. “Digraphs” are to consonants as diphthongs are to vowels, that is, they’re composed of two consecutive basic consonants. Examples of digraphs are ST, BR, GL, and QU (= KW). Trigraphs are composed of three consecutive basic consonants. Examples of trigraphs are STR and SKL.

However, the sample digraphs and trigraphs above are the sort that are found in real words. If you allow for the dictional principle that consonants at the end of a word are attached to the beginning of the next syllable (even if it begins with a consonant), we get digraphs and trigraphs galore, such as in “froM THe fartheST Hills” (consonant combinations capitalized). In fact, there are even instances where we have to sing combinations of four and five consonants, as in the phrase “aND TRuST STRongly.”

This is the point at which the interactions between consonants and vowels become important. Vowels require your mouth to be open, and consonants generally require your mouth to be almost closed. In everyday conversation, it’s okay to allow them to run together a bit because the person listening to you is close enough to deal with the blurring or, in the worst case, can ask you to repeat what you’ve said. When we sing, however, we get only one chance to communicate the message of our song, and so it’s essential that our diction be crystal clear. Consequently, we have to be much more precise in our pronunciation of words. This means that we must use much more mouth/jaw/tongue/lip action to ensure that our words are clear.

Matters are complicated still further in a choir because there are many people who have to say the same thing at the same time. There are various schools of thought on just how to achieve this, and herewith I present my own view:

- Vowels define pitch and tone, and are sung with an open mouth.

- Diphthongs and triphthongs (i.e. multiple vowels) are sung by sustaining the first vowels of the combination for as long as possible, followed by a rapid transition through the other vowel(s) in the combination.

- Consonants define rhythm, and are sung with a [nearly] closed mouth.

- Because consonants define rhythm, they also define word boundaries, and must be placed accordingly.

- Correct placement of consonant is achieved by:

- making them as short as possible.

- placing consonants which begin syllables exactly on the notes to which they belong.

- attaching consonants which end syllables to the beginning of the next syllable. Example: “Find us faith-ful” becomes, dictionally speaking, “FI-NDU-SFAI-THFU-L“

Because consonants define word boundaries, digraphs, trigraphs, etc. which span words must be examined to determine whether they must be separated to attain dictional clarity in cases where lack of separation will distort the meaning of the text. This may result in exceptions to rule (5). Example: “FRIENDS COME” must be separated to avoid singing “FRIEND SCUM” (oh, my poor de-emulsified buddy…). Special cases occur when a rest follows a syllable:

- A terminal vowel is best defined by ending the syllable with a very, very light puff of air, indicated by “(H).” (H), which should be inaudible, has the effect of killing the vowel are the desired instant.

- A terminal consonant is placed on the subsequent rest, usually also with an (H) following it.

- When singing rapid-fire syllables, modify consonants toward the top of their respective “diamond charts” to make them shorter and more intense. This will keep them in proper proportion to the vowels around them. Modify voiceless and vocal explosive consonants to be somewhat more explosive and more voiceless and modify vocal sustained and sibilant consonants to be a harder, shorter sibilant sound. In particular, always sing “S” as if it’s written “TS” (this is a tip from Weston Noble). Example: “My volleyballer is a guy with scars on his face” becomes “My folleypaller iss a kuy with sskarss on hiss ffasse.”

Next time: A short discussion of how style affects diction. Meanwhile, examine every lyric to see if there are places where dictional modifications are necessary to achieve the clarity required to communicate the message of the piece.

It may feel that I’m rushing through this series on diction a bit. You’re right – I started it with great hopes and realized only a couple of weeks ago that the seniors would miss the last installations if I didn’t try to compress things. Perhaps I’ll go through this material again in more thorough fashion in four or five years. Thanks for bearing with the higher concentration of information!

6 comments

Skip to comment form

Should “faces” and “garden” be pronounced as “fay-sez” and “gar-den” or fay-siz” and “gar-din” when singing?

Author

Hi John,

Thanks for the interesting question!

My personal rule is: “Whatever way will cause the audience to understand the text as it’s written.” I’d suspect that there may be a reason to vary the pronunciation *a little bit* based on the local regional accent, but in general if you’re using Latin-ish vowels, I’d lean toward “gah(r)-den” and “fay-se(ss)”, where the parenthesized consonants are softer/gentler than they would be pronounced in normal (unsung) conversation. My reason for the (r) is that R tends to have a grindy/growly sound, and often impedes the quality of the sound, especially in American English – for that reason, I think of it as a not-vowel and not-consonant. If you’re singing a Baroque piece, however, you might also consider using the uvular R that those who have lots of experience in the music from that period use.

My reason for the (ss) at the end of “faces” is due to a compromise between producing a sound that the listener will hear as Z, but which won’t be a voiced, closed consonant that might affect the tone and pitch adversely. If keeping the qualities of the preceding vowel intact was my only concern, I’d use a hard S, but that could confuse the listener. So I’d probably choose to go between the two extremes and use (ss) – but *not* a prolonged S sound, because long sibilants stand out far too easily (just listen to some congregational singing… 😉 ).

Without knowing which anthem or hymn you’re referring to, I’d hazard a guess, as well, that the tempo and the words before and after “faces” and “garden” will to a minor degree determine the pronunciation – that’s because singing is about the entire text, not just one or two words. So… it’s important to sing every word, but it’s also important to know how to get to each word, and how to move on to the next one.

Hope this helps!

Larry :)…

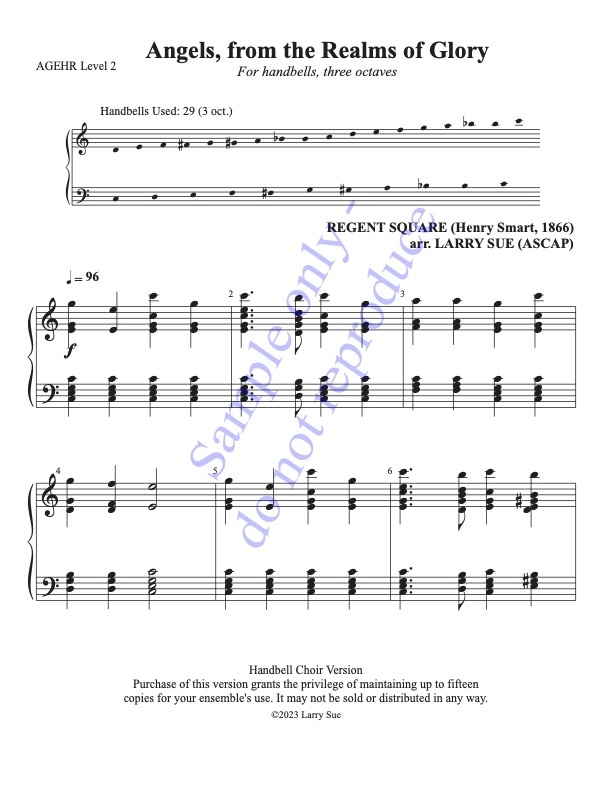

Hi, thanks so much for making this invaluable reference available! I have a question about the word “worship” In the South, we often alternate between how we say the last syllable. Some people pronounce ship as ship all other times pronouncing ship as shep or ship. I have run into this dilemma and how to pronounce the word worship in the song Angels from the realms of Glory and specifically where are part of the chorus says come and worship, come and worship, worship Christ the newborn king. Somehow it seems too repetitive to pronounce the last syllable of the word worship, each time, as ship. I lean towards pronouncing it as ship a couple of times and then ending with it as pronounced shup. Any advice? Thanks so much and God bless…

Author

Hi Meleah,

I’d say the same sort of dictional issues exist no matter where you are in the world. It’s especially true in the US, because American English has lots of phonemes that fight with good diction, good timbre, and good tone (for instance, “hum” a song, except do so on the letter R). That could mean that how you modify enunciation could change the perceived meaning of the text, i.e. in some places, “wor-shep” may sound like “wash up” to someone from out of town. Another example: We had to break the approximate rule of thumb “attach the final consonant to the beginning of the next word” when we sang the phrase “Friends come and go” (because we didn’t think any of us had scummy friends, of course).

My key idea has been to ensure that the text is understood clearly when the choir sings it. That means that the apparent “rules of diction” are better expressed in “Pirates of the Caribbean” style: not really rules, more like guidelines. You’re the director, and you know how your choir sounds, so if you find it communicates best to change the enunciation of “worship” each time, then that’s what you should do. The same applies if it works best to sing them all the same way. I’d say that if you explain what you’re trying to accomplish, the choir will be willing to work on the nuances until it all works correctly.

Best wishes as you explore your options!

Larry

Hi Larry, thank you for this very helpful site.

Christmas season is here! Our choir is rehearsing a number with lots of “glory’s” some long some short. How should we pronounce this word. Years ago I remember a choir director instructing us to pronounce it glaw-e or almost glahde. Thanks for your help.

Author

Hi Sue!

In my thinking, the bugaboo with respect to the word “glory” is the R. Because American pronunciation considers that letter important, that results in a tendency to “grind” Rs when we sing them the way we use them in conversation. Unfortunately, that leads to quite a bit of imprecision in choral presentation, because it’s difficult to get everyone to agree on the duration of the consonant. That duration also can affect intonation, since R can be a pitched sound. So the best answer is that the R should be as short as possible.

Your choir director did indeed show you two possible ways to handle “glory”. The “glaw-e” does well eliminate grinding of the R, but requires some work to unify the transition between “glaw” and “-e” because of the vowel-to-vowel sequence. The “glah-(d)e” pronunciation substitutes the (d)*, which is short in duration and therefore more easily can define the needed rhythm. A third way is to use an “uvular R”, where the R is described as “flipped”; it’s executed by touching the back of the tongue to the palate near the uvula – the resulting pronunciation is rather like “glaw-He”, where the H is more aspirated than a normal h.

Which one should you use? My answer is that you should use whatever will make the lyric clear to the listener. Of the three choices above, I’d most often start with “glah-(d)e” because it’s the easiest one to execute. One way to get at this is to let your singers start with “glahddie”, and then have them de-emphasize the R in “glory” until you get what you want. Another alternative is to use a mixed approach with most singers using “glah-e” and a few using one of the other approaches – the former group will define clean pitches, which the latter will add definition to the rhythm of the lyric; this also provides a way to soften the bit of punchiness that the D sound contributes.

Fun observation: If everyone works to make their Rs as short as possible, some combination of the three approaches should happen. As long as “glory” is what you hear your choir singing, it really doesn’t matter who’s using which approach. Then it’s up to you to provide the small bit of direction for them to know when R happens.

Hope this helps!

Larry

*(d) is most similar to a Spanish “d”, which is light and gentle.